Binghamton Main Library

Click images for larger versions

George F. Johnson Memorial Library, Endicott

DePaul University, Chicago & Impractical Labor in Service of the Speculative Arts (ILSSA)

This is what Lois Kessler, San Diego State University, told students in her classes on the last day of classes (Women’s Studies, Human Sexuality):

There is a dimension of human experience that we have not really touched on this term and I’d like to say a few words regarding that aspect. It has to do with mutual respect, the lack of interest to exploit acceptance of equality, intimacy, and involvement. It has to do with compassion, warmth, tenderness transcending the self. If I had just one wish for each and every one of you, I would wish you the most fragile of all human conditions.

I would wish you love.

Transcribed from her class notes.

Lois’s obituary, San Diego Union Tribune.

NYT, But Always Meeting Ourselves

NYT, But Always Meeting Ourselves

O that awful deepdown torrent O and the sea the sea crimson sometimes like fire and the glorious sunsets and the figtrees in the Alameda gardens yes and all the queer little streets and the pink and blue and yellow houses and the rosegardens and the jessamine and geraniums and cactuses and Gibraltar as a girl where I was a Flower of the mountain yes when I put the rose in my hair like the Andalusian girls used or shall I wear a red yes and how he kissed me under the Moorish wall and I thought well as well him as another and then I asked him with my eyes to ask again yes and then he asked me would I yes to say yes my mountain flower and first I put my arms around him yes and drew him down to me so he could feel my breasts all perfume yes and his heart was going like mad and yes I said yes I will Yes.

This is the 1959 edition of the Green Book, used in the 2018 film:

More here: NYPL & Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture

Update: Green Book: A Guide To Freedom, Smithsonian Channel documentary

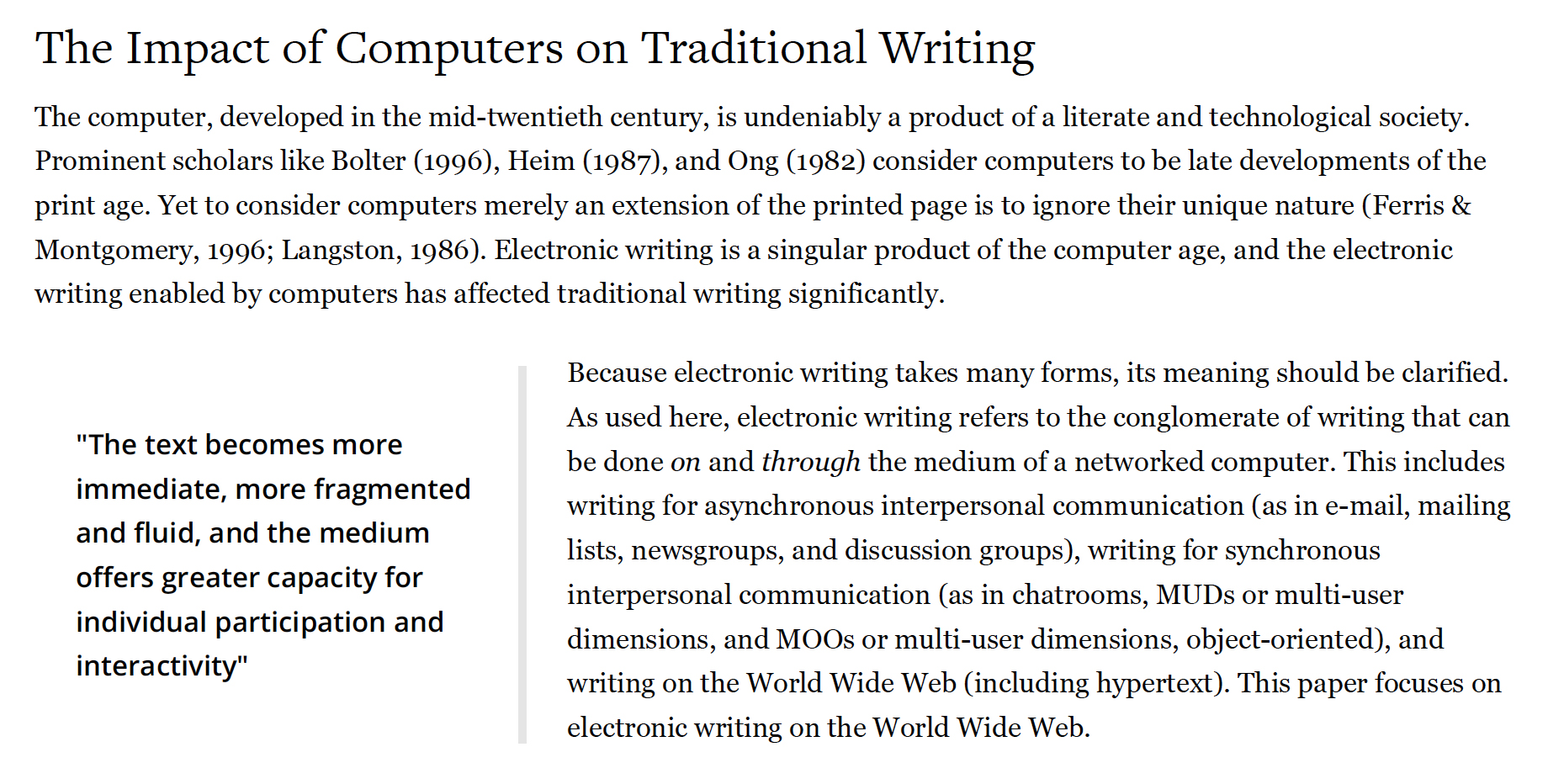

Written expression differs from oral expression in that it is dependent entirely on the alphabetic word — and not on the visual and vocal elements that help people communicate in face-to-face speech. Writing requires a codifiable medium to convey meaning. Also, it uses a vocabulary, based on known conventions and rules of usage, to create new ideas. In written expression, discrete elements (the alphabet) are combined and recombined to help convey new ideas, often using new words created to meet the needs of conveying those new ideas. Finally, written language must have a fixed relationship with spoken language, so that people can communicate the same thought in two different media simultaneously — as in reading to one another. These elements give writing its characteristics of permanence and completeness. As opposed to the transience of spoken language, writing has a lasting, permanent quality about it. Written language is less redundant, more planned. Meaning and shades of meaning are conveyed by carefully chosen and placed words. Meaning may be modified by deleting, editing, and otherwise changing the written words, unlike oral language, where once words are said out loud, they cannot be unsaid, only explained. Sequentiality, like the subject-verb-object sequence in English, is important in writing; spoken language is often understood even when the structure of the sentence is fractured. In written language, the presence of the receiver is not required, and the constraints of time and space are removed. Given these factors, writing can be more analytical than oral communication.

With the mechanization of writing, the characteristics of written language were refined and expanded. The invention of print led not only to the expansion of literacy, but to the gradual development of a number of factors with profound cognitive and expressive impacts. Print concretized the permanence of writing. Until the printing press, writing was fragile, with its permanence dependent on the preservation of an often single piece of parchment or reed (Eisenstein, 1983). Print introduced durability and multiple copies, and “embedded the word in (visual) space more definitively” (Ong 1982, p. 123). It also introduced hierarchies, which in turn introduced lists and indexes. The development of print was significant in that it reinforced the linearity and sequentiality of writing while focusing on the hierarchical thinking that was essential to the eventual flowering of modern science. The permanent nature of print also led to the preservation of language. The mass dissemination of printed texts meant both fixity and standardization of content (Eisentsein, 1983).

— Sharmila Pixy Ferris, “Writing Electronically: The Effects of Computers on Traditional Writing,” Journal of Electronic Publishing Volume 8, Issue 1, 2002.

A few years ago, when it suddenly occurred to us that the internet was a place we could never leave, I began to keep a diary of what it felt like to be there in the days of its snowy white disintegration, which felt also like the disintegration of my own mind. My interest was not academic. I did not care about the Singularity, or the rise of the machines, or the afterlife of being uploaded into the cloud. I cared about the feeling that my thoughts were being dictated. I cared about the collective head, which seemed to be running a fever. But if we managed to escape, to break out of the great skull and into the fresh air, if Twitter was shut down for crimes against humanity, what would we be losing? The bloodstream of the news, the thrilled consensus, the dance to the tune of the time. The portal that told us, each time we opened it, exactly what was happening now. It seemed fitting to write it in the third person because I no longer felt like myself. Here’s how it began.

She opened the portal, and the mind met her more than halfway. Inside, it was tropical and snowing, and the first flake of the blizzard of everything landed on her tongue and melted.

Close-ups of nail art, a pebble from outer space, a tarantula’s compound eyes, a storm like canned peaches on the surface of Jupiter, Van Gogh’s Potato Eaters, a chihuahua perched on a man’s erection, a garage door spray-painted with the words ‘STOP NOW! DON’T EMAIL MY WIFE!’

Why did the portal feel so private, when you only entered it when you needed to be everywhere?

The amount of eavesdropping was enormous. Other people’s diaries streamed around her. Should she be listening to the conversations of teenagers? Should she follow with such avidity the compliments rural sheriffs paid to porn stars, not realising that other people could see them?

She lay every morning under an avalanche of details, blissed: pictures of breakfasts in Patagonia, a girl applying foundation with a hardboiled egg, a shiba inu in Japan leaping from paw to paw to greet its owner, white women’s pictures of their bruises – the world pressing closer and closer, the spider web of human connection so thick it was almost a shimmering and solid silk.

It was a mistake to believe that other people were not living as deeply as you were. Besides, you were not even living that deeply.

She opened the portal. ‘Are we all just going to keep doing this till we die?’ everyone was asking.

— LRB, “The Communal Mind: Patricia Lockwood travels through the internet”

Borrowing & expiration apparatus, from books accessed on archive.org; click images for larger versions.

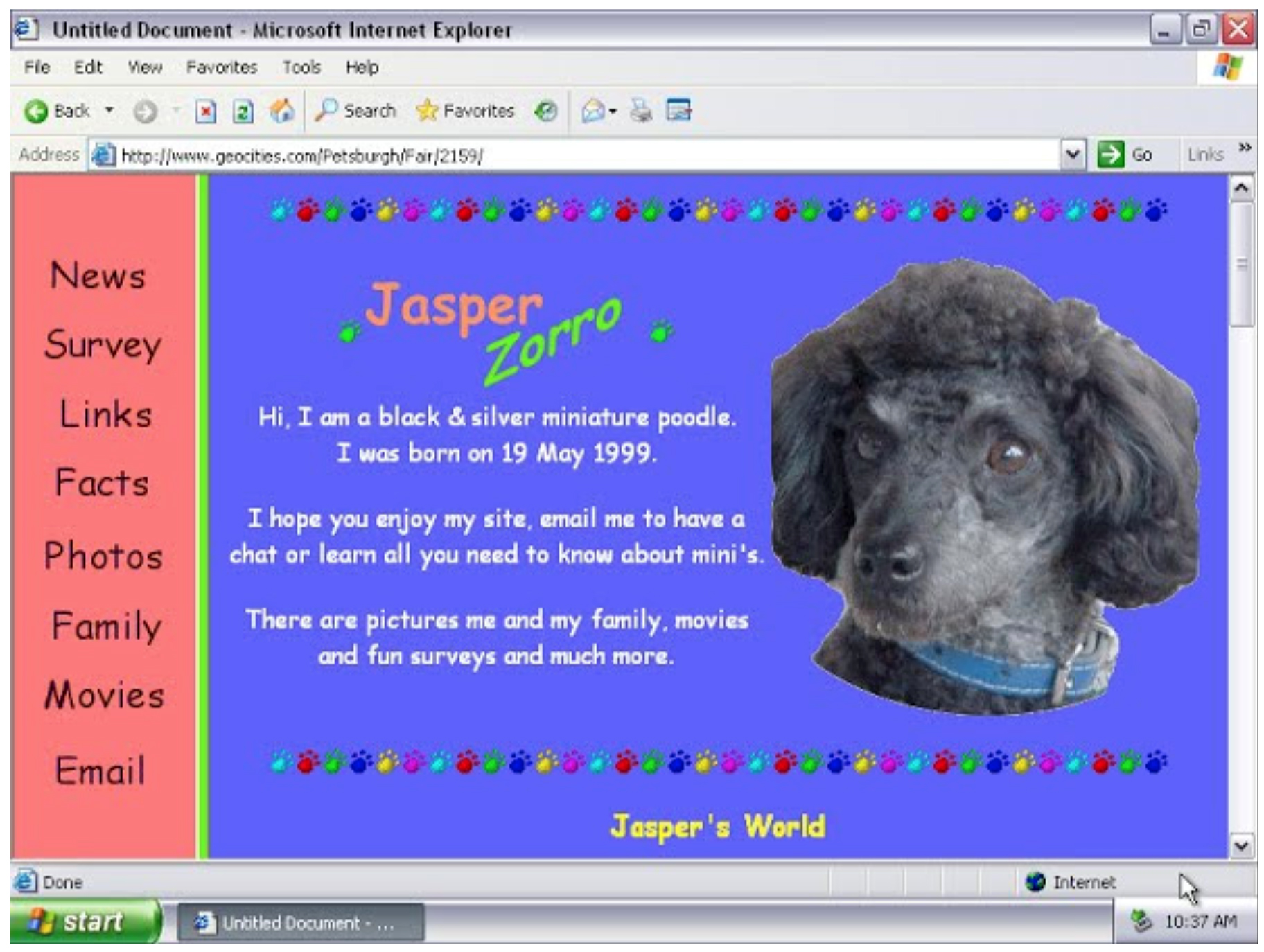

“[GeoCities] was, for hundreds of thousands of people, their first experience with the idea of a webpage, of a full-color, completely controlled presentation on anything they wanted,” Jason Scott, the founder of Archive Team, explained at a talk in 2011. “For some people, their potential audience was greater for them than for anyone in the entire history of their genetic line. It was, to these people, breathtaking.”

Laurent de La Hyre, from his series “The Seven Liberal Arts,” 1649-50. Inscription translation: “A meaningful and literate word spoken in a correct manner.”

See also Allegory of Music (Met Museum) and Allegory of Geometry (The Athenaeum)

Memoirs of the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum of Polynesian Ethnology and Natural History, Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard Univ., Vol 1, 1899-1903.

You do not have to be good.

You do not have to walk on your knees

for a hundred miles through the desert repenting.

You only have to let the soft animal of your body

love what it loves.

Tell me about despair, yours, and I will tell you mine.

Meanwhile the world goes on.

Meanwhile the sun and the clear pebbles of the rain

are moving across the landscapes,

over the prairies and the deep trees,

the mountains and the rivers.

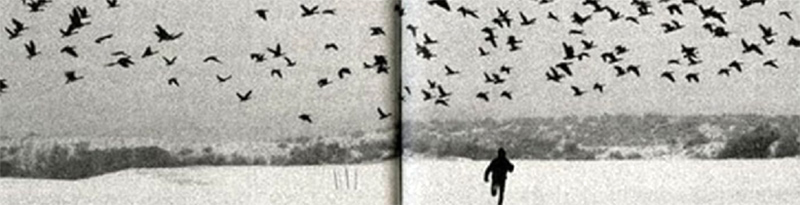

Meanwhile the wild geese, high in the clean blue air,

are heading home again.

Whoever you are, no matter how lonely,

the world offers itself to your imagination,

calls to you like the wild geese, harsh and exciting –

over and over announcing your place

in the family of things.

— Mary Oliver

“Wild Geese”

The Summer Day

Who made the world?

Who made the swan, and the black bear?

Who made the grasshopper?

This grasshopper, I mean-

the one who has flung herself out of the grass,

the one who is eating sugar out of my hand,

who is moving her jaws back and forth instead of up and down-

who is gazing around with her enormous and complicated eyes.

Now she lifts her pale forearms and thoroughly washes her face.

Now she snaps her wings open, and floats away.

I don’t know exactly what a prayer is.

I do know how to pay attention, how to fall down

into the grass, how to kneel down in the grass,

how to be idle and blessed, how to stroll through the fields,

which is what I have been doing all day.

Tell me, what else should I have done?

Doesn’t everything die at last, and too soon?

Tell me, what is it you plan to do

with your one wild and precious life?

Oliver’s NYT Obituary (01/17/2019)

On another time, when he was walking with a certain Brother through the Venetian marshes, he chanced on a great host of birds that were sitting and singing among the bushes. See- ing them, he said unto his companion: "Our sisters the birds are praising their Creator, let us too go among them and sing unto the Lord praises and the canonical Hours." When they had gone into their midst, the birds stirred not from the spot, and when, by reason of their twittering, they could not hear each the other in reciting the Hours, the holy man turned unto the birds, saying : "My sisters the birds, cease from singing, while that we render our due praises unto the Lord." Then the birds forthwith held their peace, and remained silent until, having said his Hours at leisure and rendered his praises, the holy man of God again gave them leave to sing. And, as the man of God gave them leave, they at once took up their song again after their wonted fashion. -- The life of Saint Francis by Saint Bonaventura c. 1270 page 89

Giotto di Bondone, St. Francis Preaching to the Birds, 1297 – 1299.

People tend to hold overly favorable views of their abilities in many social and intellectual domains. The authors suggest that this overestimation occurs, in part, because people who are unskilled in these domains suffer a dual burden: Not only do these people reach erroneous conclusions and make unfortunate choices, but their incompetence robs them of the metacognitive ability to realize it. Across 4 studies, the authors found that participants scoring in the bottom quartile on tests of humor, grammar, and logic grossly overestimated their test performance and ability. Although their test scores put them in the 12th percentile, they estimated themselves to be in the 62nd. Several analyses linked this miscalibration to deficits in metacognitive skill, or the capacity to distinguish accuracy from error. Paradoxically, improving the skills of participants, and thus increasing their metacognitive competence, helped them recognize the limitations of their abilities.

— “Unskilled and unaware of it: how difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments.” Journal of Social Psychology. 1999 Dec;77(6):1121-34. [Link]

“Dr. James attributes the differences to the messiness inherent in free-form handwriting: Not only must we first plan and execute the action in a way that is not required when we have a traceable outline, but we are also likely to produce a result that is highly variable.”

“That variability may itself be a learning tool. ‘When a kid produces a messy letter,’ Dr. James said, ‘that might help him learn it.'”

Learning about substratum with the artist Kathryn Trumbell Fimreite:

Substratum: Latin: substrātum underlying layer, background; an underlying principle on which something is based; a basis, a foundation, a bedrock; a permanent underlying thing or essence in which properties inhere, more commonly called substance (philosophy); an underlying stratum, esp. that beneath the soil or other surface feature (geology); a lower class or stratum of society, esp. one which is characterized by poverty or criminality (sociology); a language spoken in a particular area at the time of the arrival of a new language, and which has had within that area a detectable influence on the elements or features of the new language (linguistics)

— OED

“It should have been bigger. More momentous. When you are holding something in your hands that is the last of its kind, you feel as if it ought to be more … special. A collectible. Something worthy of a time capsule, or a memory box.”

“But the last regular print issue of Glamour, which landed on newsstands on Tuesday, ahead of the magazine’s complete pivot to digital (with, O.K., the occasional special physical product, exactly when to be determined), is an anemic little thing, not even 100 pages.”

“There’s no drumroll for the “goodbye to paper,” no editor’s letter extolling the virtues of the more immediate future — we’re off the newsstand but on all your devices! There are no clues that this is a milestone moment in the struggle for survival of old media, and how women relate to the sisters-in-arms-advice-over-wine voice of the magazine, one that is now moving from their mailboxes to their inboxes.”

— NYT/Friedman: “Saying Goodbye to Glamour”

“The replacement of the consciously curated Web by a more automatized, algorithmically driven network mirrors the evolution of the financial markets alongside which it has developed in the modern information economy. The investment market segment of that economy has been adapting to the realization that the curatorial choices of professional money managers and actively managed funds could not outperform randomly indexed big-data sampling of the market as a whole. Recognizing the significance of this paradigm shift, Paul Stephens has written with keen insight about “strategies of passive indexing” in the economic world of big data and its correlation to conceptual writing practices.”

Dworkin, Craig. “Poetry in the Age of Consumer-Generated Content.” Critical Inquiry 44 (Summer 2018).

Equally important for engagement in a narrative is the unobtrusiveness of the display or substrate on which the written text appears. Readers do not want to be interrupted by being forced to pay attention to the paper, binding, or spine on which they engage narrative stories; they want to become “lost” in a book (Nell, 1988). Analogously, interface features of digital devices should recede into the background during reading, enabling engagement with the narrative story world. This requires, for instance, that readers ignore the ergonomics of page turning and text navigation. The failure of dedicated, electronic literature (e.g., hypertext novels) to reach a wide audience is plausibly related to the fact that the reader has to engage actively in navigational decisions during reading and interact — cognitively and physically — with the work. This constant interaction, Holland (2009) argues, makes immersion in the “world” of the hypertext story or poem impossible: “The [real] world cannot evaporate, nor can we feel transported into the world of the story. Instead, we are busy at the computer.” (p. 41). Given such apprehensions, it is important to determine empirically whether readers’ engagement with a literary narrative is affected by whether they read it in print or on a tablet. The experiment reported here was designed to do so.

Theoretical background “Sense of the text” on paper and screen Empirical research has examined cognitive aspects of text reading on paper and screens, and the available results are mixed. Some recent studies report little or no difference in comprehension between paper and screen reading (Margolin et al., 2013; Kretszchmar et al., 2013), whereas other studies suggest that reading lengthy linear texts on screen may impede the high-level processes underlying comprehension, metacognition, and recall (Ackerman & Goldsmith, 2011; Jeong, 2012; Kim & Kim, 2013; Mangen, Walgermo, & Brønnick, 2013; Wästlund, Reinikka, Norlander, & Archer, 2005). Of particular relevance to the present study is research demonstrating the adverse effects of the spatio-temporal intangibility of digitized texts on reading comprehension (cf. Mangen et al., 2013). When reading on paper, readers have immediate sensory access to text sequence, as well as to the entirety of the text. They can discern visually, as well as sense kinesthetically, their page by page progress through the text; the paper substrate provides physical, tactile, and spatiotemporally fixed cues to text length (Mangen, 2006; Sellen & Harper, 2002).

In contrast, when reading on screen, readers may see (e.g., using page numbers) but not kinesthetically sense their page by page progress through the text. Hence, overview of the text’s organization and structure (Eklundh, 1992; Piolat et al., 1997) — the reader’s “sense of the text” (Haas, 1996) — may be diminished. While such loss of text length overview and of location in the text may matter for reading in general, having a “sense of the text” may matter especially for narrative genres. On the one hand, because narratives are based on a chronological ordering of actions and events, a parallel kinesthetic sense of the unfolding reading event may support immersion in the narrated world. On the other hand, separation from this kinesthetic sense of the physical reading event may be precisely what prevents immersion in the narrative world — and becoming “lost” there. Research to date does not enable affirmation of either of these conflicting possibilities.

— Mangen, A. & Kuiken, D. (2014) “Lost in an iPad: Narrative engagement on paper and tablet.” Scientific Study of Literature, Volume 4, Issue 2, Jan 2014, p. 150 – 177.

“ … what Jonathan Edwards (Yale, class of 1720; appointed president of Princeton in 1758) called “beauties that delight us and we can’t tell why — as when “we find ourselves pleased in beholding the color of the violets, but we know not what secret regularity or harmony it is that creates that pleasure in our minds.”

— Jonathan Edwards, 1752.

— Quoted in Andrew Delbanco: College: What It Is, Was, and Should Be (p. 40), 2012.

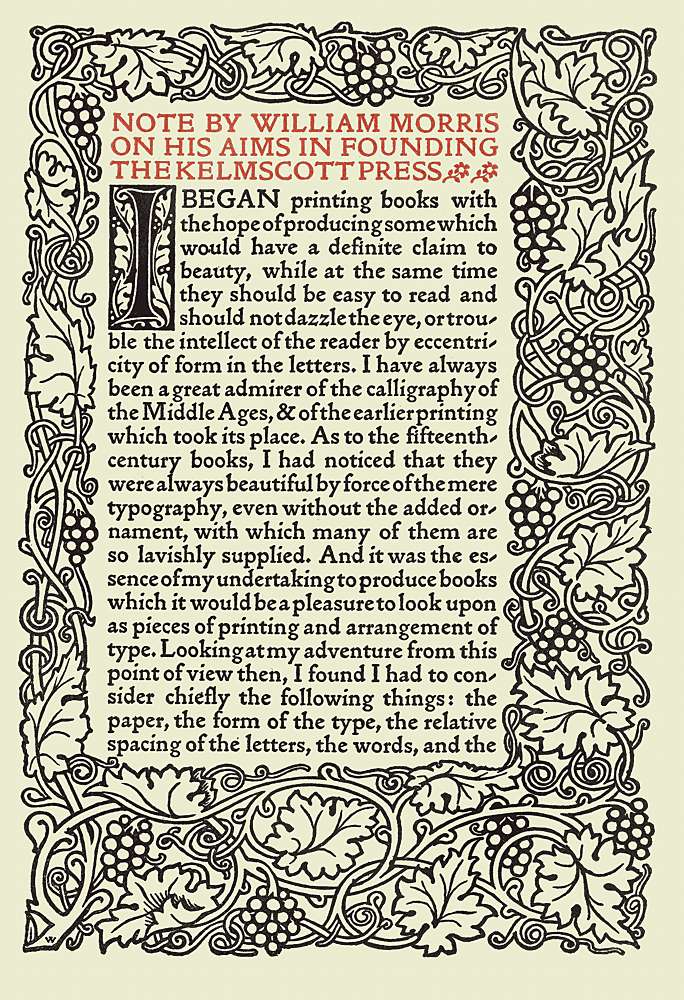

“For Morris, the books of his time were symptomatic of the shortcomings of modern society: they were ugly, badly made and mass-produced.”

— via Hornbake Library, University of Maryland’s College Park

“The assumption now current, that the test of a university is its success in vaulting graduates into the upper tiers of wealth and status, obscures the fact that the United States is an enormous country, and that many of its best and brightest may prefer a modest life in Maine or South Dakota. Or in Iowa, as I find myself obliged to say from time to time. It obscures the fact that there is a vast educational culture in this country, unlike anything else in the world. It emerged from a glorious sense of the possible and explored and enhanced the possible through the spread of learning. If it seems to be failing now, that may be because we have forgotten what the university is for, why the libraries are built like cathedrals and surrounded by meadows and flowers. They are a tribute and an invitation to the young, who can and should make the world new, out of the unmapped and unbounded resource of their minds.”

— Marilynne Robinson, “Save Our Public Universities: In Defense of America’s Best Idea”

“Ludwig Wittgenstein wrote in a 1919 letter that his work ‘consists of two parts: the one presented here plus all that I have not written. And it is precisely this second part which is the important one.’ In theology, apophaticism refers to the idea that what we cannot say about God is more fundamental than what we can; in literature and other works of art, Knight argues, it functions as a way of continuing to speak and write even in the face of the unspeakable.”

— Knight, Omissions are not Accidents: Modern Apophaticism from Henry James to Jacques Derrida. University of Toronto Press, 2010.

Marianne Moore, “Preface” to The Complete Poems of Marianne Moore, 1982.

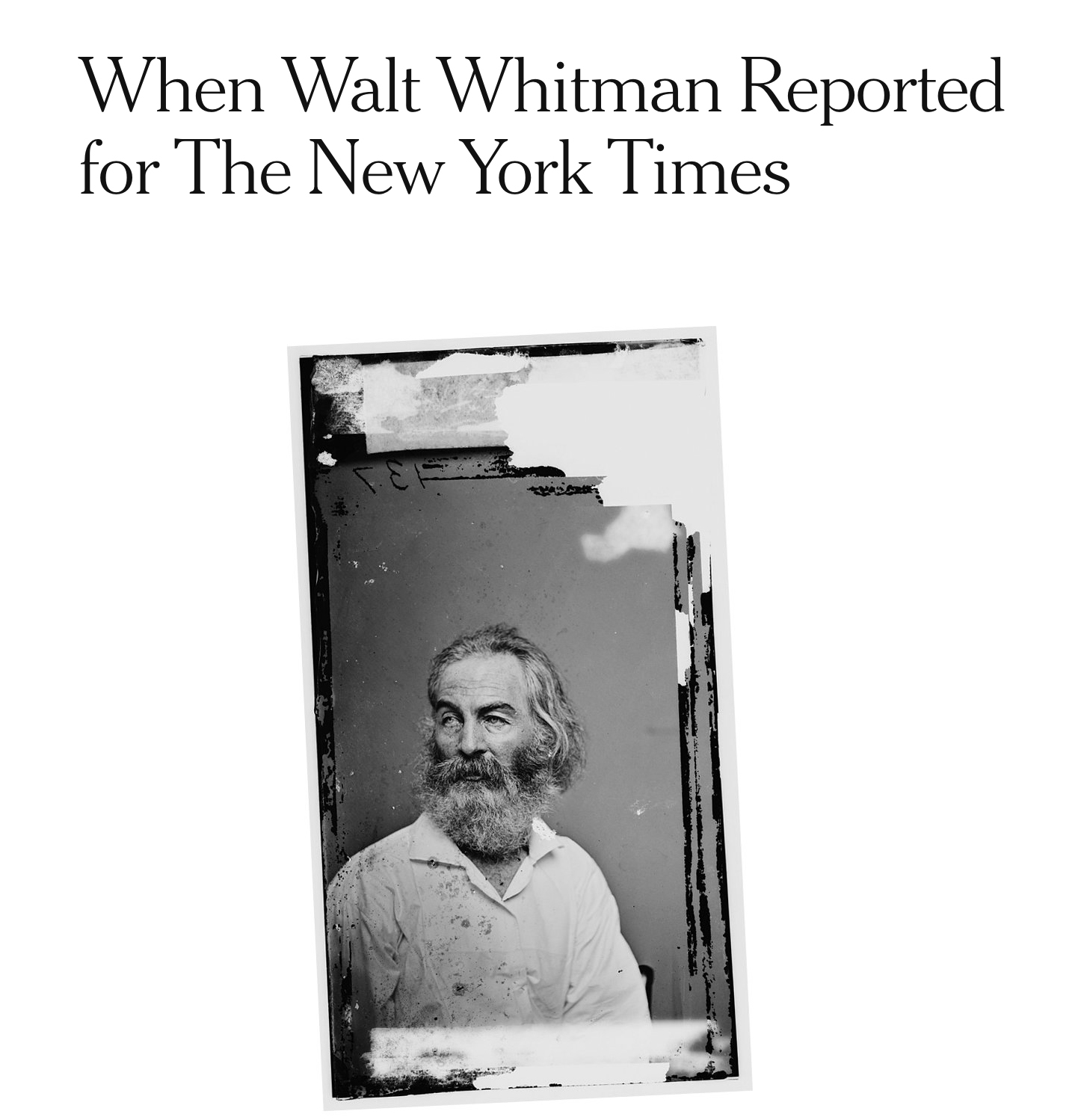

“Reporting on Abraham Lincoln’s second inauguration just over a month before Robert E. Lee’s surrender, a New York Times reporter juxtaposed the scene of the inaugural ball that took place in the patent office in Washington to his memory, two years earlier, of when the same location housed the wounded and dying.”

“Tonight,” he wrote. “Beautiful women, perfumes, the violins’ sweetness, the polka and the waltz; but then, the amputation, the blue face, the groan, the glassy eye of the dying, the clotted rag, the odor of the old wounds and blood and many a mother’s son amid strangers, passing away unintended there.”

“That reporter was the poet Walt Whitman. During the Civil War, The Times employed a large staff to cover the war all across the country, sending information with unprecedented speed by way of railroad and telegraph. The rapidly evolving and war-torn country provided tales of journalists that were as rich as their reports.”

Library note:

The book, which collects what may have been considered representative work of the school’s award-winning writers, is composed of a collaboratively written story, letters, and essays in series on miscellaneous topics—likely assignments—all of which immortalize the voices, but also the bodies, of some of St. John’s first students.

One of the most intriguing sections of the book is composed of three essays on “the (un)certainty of death,” by William Maguire, Thomas Ward, and Wilson Durack. Ward’s essay is dated February 7th, 1873, which suggests that all three essays may have been composed within the same (academic) year.

— Via St. John’s University Archives and Special Collections

From the article’s conclusion:

“‘And what of me? For the moment in third grade, but next year it’s fourth, and then fifth, and then ninth, and then college, and then middle age, and then, in time’s fullness, I’ll altogether cease. Oh, my life. What am I doing with my life?’ Jacobs has since taken his mind off the subject by trying to find school binders that don’t have totally stupid graphics on them.”

CHAPTER V.

Rhetoric.

TECHNICAL STUDY.

GENERAL CONDITIONS.

More than any other of the subjects of the mediaeval curriculum, Rhetoric shows the distinctive characteristics of the age. While in the other branches, grammar especially, the methods and ideals of the later Empire were largely followed, being modified only to meet the changing requirements of new conditions, the study of rhetoric assumed an entirely new character. On the one hand the old practical rhetorical training of the Roman period was almost entirely discarded or was reduced to a mere mastery of the technical rules of the science. On the other hand, one insignificant phase of classical rhetoric the study of the Epistle and “Dictamen” was overemphasized and developed to such an extent as to displace in the curriculum the study of rhetoric proper.

This change was not made without reason. The decadence of the rhetorical schools of Rome was caused by the deadening formalism which resulted from perpetuating the ideal of training orators at a time when the world had no use for orators. In the days of Cicero the training in oratory was in harmony with the spirit of the age. Since its noblest use was then the defense of liberty, his seven works on eloquence were timely treatises indeed. But in the later empire, in spite of changed conditions, this formal training in oratory remained, as we have seen in a preceding chapter, the same as in the period of Cicero. Such an artificial and lifeless system of education could not but be debasing in its influence. Now, as was also shown in a former chapter, while the Christianized Roman world permitted the pagan schools to die, it was not averse to appropriating for its own purposes the essential elements of the culture which these various schools imparted. But it could not, from the nature of things, accept the educational ideal of the ancient world the training of the orator. Therefore rhetoric, the basis of education in the Empire, lost its importance in the middle ages and could no longer be the keystone of the educational arch. (pp. 52-53)

Abelson, The Seven Liberal Arts, a Study in Mediaeval Culture, 1906.

Earl Shorris: I’ve argued that the humanities provide the most practical education. If we can stipulate that knowing is better than not knowing, then the comparison is between education, as in studying the humanities, and training, as in learning to operate a computer or mop floors or pull a tooth or make out a will. We can start from the simplest kind of training, that is, training to repeat the least complex task, which might be mopping floors or repetitively entering numbers into a computer. Such work is poorly paid, with little or no chance for advancement. Historically, the poor have been trained to do such tasks as a way of maintaining a low cost labor force. During the industrial revolution, an ethic (Weber’s Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism is the best description of it) developed that kept the poor “happily” at their labors.

Training for complex tasks, such as dentistry or engineering, is more demanding, but nevertheless training, in that it teaches the student to do something that has been done before: pull a tooth, build a bridge, and so on. Compare even that kind of training to education in the humanities—philosophy, art, history, literature, and logic, in Petrarch’s formulation. The distinction is between doing and thinking, between following and beginning. Nicolaus Copernicus, a Polish student of the humanities, with no formal training in astronomy, quite literally turned the universe inside out. Few ideas in modern history have had more influence on scientific thinking than the Copernican Revolution. Similarly, Descartes, whose method is at the base of technological activity, was not himself a technologist or even a scientist; he was a philosopher. If America is to remain a leading nation, it will do so because of the humanities, not because of training, even of the most sophisticated kind.

Let’s apply that practicality to a person living in the second or third generation of poverty. If one has been “trained” in the ways of poverty, left no opportunity to do other than react to his or her environment, what is needed is a beginning, not repetition. The humanities teach us to think reflectively, to begin, to deal with the new as it occurs to us, to dare. If the multi-generational poor are to make the leap out of poverty, it will require a new kind of thinking—reflection. And that is a beginning.

— Mass Humanities, Social Transformation through the Humanities: An Interview with Earl Shorris

“This illustration resonated with U.S. residents in the post–Civil War era in part because the vision of expansionism as “progress,” and progress defined as the introduction of domesticity to the wilderness, fit with the hegemonic gender norms of the era. After the upheaval and staggering violence of four years of Civil War, survivors turned away from heroic individualism and looked toward work and home for meaning. The growth of the country, “from sea to sea,” in the decades before the war was idealized as an essentially peaceful process, a period when harmony reigned and Americans were unified in pursuit of their destiny. American Progress is a vision of expansionism, both domesticated and restrained.”

From Amy S. Greenberg, Manifest Manhood and the Antebellum American Empire — Cambridge University Press, 2005.

Also as the book cover on Does Technology Drive History? The Dilemma of Technological Determinism.

“Compared to the phosphorescent garbage heap of DOS – an intimidating jumble of letters and commands – the world one entered into when flicking on a Macintosh was a clean, well-lit room, populated by wry objects, yet none so jarring that it threatened one’s comforting sense of place. It welcomed your work.” (Levy 157)

In the Old Testament there was the first apple, the forbidden fruit of the Tree of Knowledge, which with one taste sent Adam, Eve, and all mankind into the great current of History. The second apple was Isaac Newton’s, the symbol of our entry into the age of modern science. The Apple Computers symbol was not chosen purely at random: it represents the third apple, the one that widens the paths of knowledge leading toward the future. (Gassée 10-11)

This chapter, then, concerns itself with two significant aspects of this roughly ten year period: first, the shift from seeing a user-friendly computer as a tool that encourages understanding, tinkering, and creativity to seeing a user-friendly computer in terms of an efficient work-station for productivity and task-management and the effect of this shift particularly on digital literary production. Second, tightly connected to the first, this chapter concerns itself with the rupture marked by the turn from computer systems based on the command-line interface to those based on “direct manipulation” interfaces that are iconic or graphical (GUI) – a turn driven by rhetoric that insisted the GUI, particularly that pioneered by the Apple Macintosh design team, was not just different from the command-line interface but it was naturally better, easier, friendlier. As I outline in the second section of this chapter, the Macintosh was, as Jean-Louis Gassée (who headed up its development after Steve Jobs’ departure in 1985) writes without any hint of irony, “the third apple,” after the first apple in the Old Testament and the second apple that was Isaac Newton’s, is “the one that widens the paths of knowledge leading toward the future.” (11)

Despite studies released since 1985 that clearly demonstrate GUIs are not necessarily better than command-line interfaces in terms of how easy they are to learn and to use, Apple – particularly under Jobs’ leadership – successfully created such a convincing aura of inevitable superiority around the Macintosh GUI that to this day the same “user-friendly” philosophy, paired with the no longer noticed closed architecture, fuels consumers’ religious zeal for Apple products. I should note that I have been an avid consumer of Apple products since I owned my first Macintosh Powerbook in 1995. However, what concerns me is that ‘user-friendly’ now takes the shape of keeping users steadfastly unaware and uninformed about how their computers, their reading/writing interfaces, work let alone how they shape and determine their access knowledge and their ability to produce knowledge. As Wendy Chun points out, it’s a system in which users are, on the one hand, given the ability to “map, to zoom in and out, to manipulate, and to act” but, she implies, the result is is a “seemingly sovereign individual” who is mostly an devoted consumer of ready-made software, ready-made information whose framing and underlying (filtering) mechanisms we are not privy to (8).

Thus, the trajectory of this argument culminates in chapter four, in which I make it clear that the logical conclusion of this shift to the ideology (if not the religion) of the user-friendly via the Graphical User Interface (GUI) is, first, expressed in contemporary multi-touch, gestural, and ubiquitous computing devices such as the iPad and the iPhone whose interfaces are touted as utterly invisible (and so their inner workings are de facto invisible as they are also inaccessible); and, second, this full realization of frictionless, interface-free computing born out of the mid-1980s is in turn critiqued by works of activist digital media poetics. From this perspective, it is, then, no coincidence at all that Apple had actually designed something like an iPhone in 1983; at the same time that Macintosh designers were hard at work, Hartmut Esslinger, the designer of the Apple IIc, built a white landline phone complete with a built-in, stylus-driven touch-screen. (“Apple’s First iPhone”). The Apple IIc was in fact a close relative of the Macintosh in terms of portability and lack of internal expansion slots which made them both closed systems; the IIc was also released in 1984, just three months after the Macintosh.

But while chronologically proceeding from the era of the typewriter, using a media archaeology methodology to understand this particular rupture in media history means that activist media poetics plays out quite differently in the 1980s as it was an era newly oriented toward the efficient completion of tasks over and beyond a creative use or mis-use of the computer. Arguably one reason for the heightened engagement in hacking type(writing) in the mid-1960s to mid-1970s is that the typewriter had become so ubiquitous in homes and offices that it had also become invisible to its users. It is precisely at the point at which a technology saturates a culture that writers and artists, whose craft is utterly informed by a sensitivity to their tools, begin to break apart that same technology to once again draw attention to the way in which it offers certain limits and possibilities to both thought and expression. There are indeed examples of digital media activist poems that also inherit an emphasis on making, doing, hacking but – once again – it seems to me that the vast majority of these works do not appear until both the personal computer and the user-friendly computer whose GUI is designed to keep the user passively consuming technology rather than actively producing it become practically ubiquitous.

As I discuss in the first section of this chapter, activist media poetics in this particular time period mostly takes the form of experimentation with digital tools that at the time were new to writers – an experimentation that, at least under the terms set by Mckenzie Wark’s Hacker Manifesto, certainly could be framed as hacking (Wark infamously writes that “Hackers create the possibility of new things entering the world” [004] and that “The slogan of the hacker class is not the workers of the world united, but the workings of the world untied” [006]). However, as I will discuss, work by Invisible Seattle, Nichol, Paul Zelevansky, Geof Huth, and Robert Pinsky is not working to make the (in this case) command-line interface visible so much as it is openly playing with and tentatively testing the parameters of the personal computer as a still-new writing technology. This kind of open experimentation almost entirely disappeared once Apple Macintosh’s design innovations as well as their marketing made open computer architecture and the command-line interface obsolete and GUIs pervasive.

— From Lori Emerson, Reading Writing Interfaces: From the Digital to the Bookbound (University of Minnesota Press, June 2014)

Photo taken on the first day of her summer internship — and as part of a group of college guest editors — at Mademoiselle, June, 1953:

Scene recreated in The Bell Jar:

‘Come on, give us a smile.’

“I sat on the pink velvet loveseat in Jay Cee’s office, holding a paper rose and facing the magazine photographer… I didn’t want my picture taken because I was going to cry. I didn’t know why I was going to cry but I knew that if anybody else spoke to me or looked at me too closely the tears would fly out of my eyes and the sobs would fly out of my throat and I’d cry for a week….

“‘Show us how happy it makes you to write a poem.’”

— Plath, Bell Jar, chapter nine.

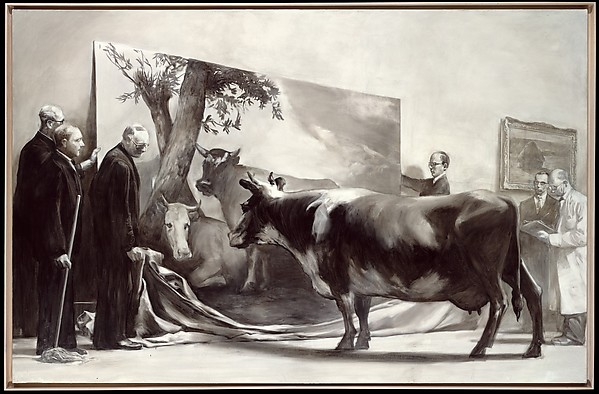

“Tansey presents a scene depicting a cow being presented a painting of two cows by the seventeenth-century painter Paulus Potter, as a group of educated-looking gentlemen in lab coats, perhaps connoisseurs (if I were a connoisseur of connoisseurs), stand attentively observing the cow. The art experts consult the cow to determine whether a work depicting cows is convincingly rendered. For the art connoisseurs, their cultivated gaze cannot judge the work adequately, because their vision is structured by aesthetic discourse. They need an innocent eye, a bestial eye. In the cow’s gaze and the anticipation of her reaction to the work, we have an echo of a similar story from antiquity concerning an artistic competition between the painters Zeuxis and Parhassios. For the competition, Zeus paints an image of grapes, fooling a bird, which comes to peck at the painting …”

— Richards, Derrida Reframed: Interpreting Key Thinkers for the Arts, 2008.

— Innocent Eye Test at the Metropolitan Museum

Key words: User-interface, ideology, values, ethics, manipulation, persuasion, rhetorics.

Introduction:

The user interface of interactive systems is the meeting point of people with

interactive communication technology (ICT). As a human product it forms a part of culture that determines us, often without our full realization. The user-interface (UI) is constructed according to a set of values of the designer and other stakeholders in the production process. Their values and goals are implicitly encoded in the interface and the documentation but can

be in conflict with the values of the user. This means the UI directs the user interaction in a way that should follow user’s intentions, but is often more subject to the intent of the designer or simply by what the system allows for by itself. This is when both the intentional and unintentional manipulation with the user starts, because he or she is presented with choices or even goals, that are inappropriate for his or her intent.

For the purpose of unmasking and decoding the inner workings of the UI we can apply semiotics with the emphasis on pragmatics, as defined by Charles Morris (1970). Semiotics is in this regard a study of semiosis, which has a syntactic, semantic and pragmatic dimension.

Syntactics is “the study of the syntactical relations of signs to one another in abstraction from the relations of signs to objects or to interpreters…” (Morris, 1970: 13) In this dimension we deal with the grammar constituting relations between the perceivable elements, or sign vehicles.

Semantics, on the other hand, “deals with the relation of signs to their designata and so to the objects which they may or do denote.” (Morris, 1970: 21) This dimension is devoted to the relation between vehiculae and the object, content, action, or “meaning” the UI represents and enables.

Pragmatics “deals with the biotic aspects of semiosis, that is, with all the psychological, biological, and sociological phenomena which occur in the functioning of signs.” (Morris, 1970: 30). This most complex dimension focuses on how we use or interpret the vehiculaobject relation, i.e., what is the sign‘s purpose? The pragmatic dimension governs how signs are used, or understood in their conventional and symbolic form. Each and every computer-based UI is a result of diverse influences.

Each and every computer-based UI is a result of diverse influences during the design process.

— Jan Brejcha, User-Interface as an Expression of Political Ideology. Magal, Solik, eds. Médiá a politika – Megatrendy a médiá. Trnava: Fakulta masmediálnej komunikácie Univerzity sv. Cyrila a Metoda v Trnave, 2011, p. 245-261.

![]()

For example?