Toward Perfection

June 4, 2013For Monday

June 2, 2013Concluding thoughts

“One purpose of a liberal arts education is to make your head a more interesting place to live inside of for the rest of your life.” —Mary Patterson McPherson, President, Bryn Mawr College

“I thought that the future was a place—like Paris or the Arctic Circle. The supposition proved to be mistaken. The future turns out to be something that you make instead of find. It isn’t waiting for your arrival, either with an arrest warrant or a band; it doesn’t care how you come dressed or demand to see a ticket of admission. It’s no further away than the next sentence, the next best guess, the next sketch for the painting of a life’s portrait that may or may not become a masterpiece. The future is an empty canvas or a blank sheet of paper, and if you have the courage of your own thought and your own observation, you can make of it what you will.” —Lewis Lapham

“It ain’t where ya from, it’s where ya at!” —KRS-ONE, Ruminations

Brainstorming how to theorize your writing and yourself as a writer

- Can you perceive of rhetoric as an ongoing negotiation between people, texts, and issues — i.e., as a way of seeing and being in the world? Can you theorize your writing from that perspective?

- Are you a serendipitous reader and thinker, open to discovery and willing to follow where your thinking and learning take you, or are you a hierarchical, confirmation-based reader and thinker? Can you theorize your writing from that perspective?

- Did you arrive at college with “funds of knowledge” or a family literacy that informs your attitude about writing? Can you theorize your writing from that perspective?

- Are you a high or low context person and writer?

- What kind of critical thinker are you, and how does that shape your writing?

- Are you committed to social justice and to social change? Is it possible to theorize your writing from that perspective?

- Do you like to engage — or to flee from — perplexity and intellectually challenging projects? Can you theorize your writing from one of those perspectives?

- Can you use DePaul’s definition of literacy to reflect on and to theorize your work? “We are helping students become more literate. By literacy, we do not mean merely learning to read and write academic discourse, but also learning ways of reading, writing, thinking, speaking, listening, persuading, informing, acting, and knowing within the contexts of university discourse(s) and the multiple discourses in the world beyond the university.”

Congratulations, Marisa — 9:40 section

May 30, 2013A contextual analysis just waiting to happen.

May 29, 2013Custom Portfolio Banners

You can use Pixlr.com to create custom banners:

- Go to Pixlr.com

- Open an image from your computer

- Resize for appropriate Digication dimensions: 779 x 200 pixels

- Add effects and/or text

- Save banner to your computer

- Insert your new banner via Portfolio Settings > Customize

- Scroll down and Save

“When Numbers Mislead”

May 26, 2013“ … adding some fat to her with Photoshop.”

From the NYT Public Editor, Margaret Sullivan:

“I asked its editor, Deborah Needleman, about one objection: that the cover model was too skinny. She responded that she, too, felt that many models were too thin, and with this one she had considered ‘adding some fat to her with Photoshop.’

“John Schwartz, a Times reporter, was among the first to react. On Twitter, he called her comment ‘jaw-dropping.’ That reflected how deeply most journalists feel about the integrity of photographs.”

Contextual Analysis of College Application Essays

“Themes of money, working, class, affluence and the economy increasingly figure in college application essays.” NYT: “Standing Out From the Crowd”

“Themes of money, working, class, affluence and the economy increasingly figure in college application essays.” NYT: “Standing Out From the Crowd”

It was ever thus.

“I would say the historian’s mind-set is the person who sees what’s going on, today, and assumes that whatever’s happening is not happening for the first time. And that whatever we’re seeing must have happened in some iteration, at some point, sometime in the past somewhere. And that those versions of the kinds of change that we see around us in various scales are just the latest installment of a very long series of similar such changes.”

“… that history is sort of repeating in some ways. But isn’t history also cumulative—that when we see it happening a second time it’s somehow different from the first time?”

New Yorker Magazine: LAPTOP U: Has the future of college moved online?

Three from Brooks

So that we have these all in one place:

“The Organization Kid” (April 2001)

“One senior told me she had subscribed to The New York Times once, but the papers had just piled up unread in her dorm room. ‘It’s a basic question of hours in the day,’ a student journalist told me. ‘People are too busy to get involved in larger issues. When I think of all that I have to keep up with, I’m relieved there are no bigger compelling causes.'”

“The Empirical Kids” (March 2013)

“In what I think is an especially trenchant observation, Buhler suggests that these disillusioning events have led to a different epistemological framework. ‘We are deeply resistant to idealism. Rather, the Cynic Kids have embraced the policy revolution; they require hypothesis to be tested, substantiated, and then results replicated before they commit to any course of action.’”

“Started at the Bottom” (May 2013)

“Most of the students had some trouble gelling with the whiter, richer student body in college and hung out mostly with fellow Hispanics. ‘We love our culture,’ said Reuben. ‘That’s what makes our group stronger and bonds us together.’ Now they seem to flow fluidly across cultural lines.”

“They seemed both hardy and a bit naïve, made more resilient by reality but not jaded by it. Their conversational styles were enthusiastic, grateful, direct and earnest. They seemed to us unself-conscious about how they present themselves — unironic, matter of fact, sincere and un-meta — not tripping in loops of self-awareness. They also have a less methodical sense of the exact steps you have to take to make it in the world.”

Hispanic or Latino?

Sometimes you don’t have to look very far to see the problem. In this Chronicle of Higher Education article on college-enrollment statistics, “Latino” is used in the headline, and “Hispanic” is the first word in the article.

The Los Angeles Times is trying to work through the issue, too, in their style guide. In that case, the discussion seems to aspire to some textual stability, where the readers’ comments below will show they still have some work to do.

What you can accomplish with the Contextual Analysis method

Evaluating the Framing of Islam and Muslims Pre- and Post-9/11:

A Contextual Analysis of Articles Published by the New York Times

Abstract:

Media plays an integral role in forming public perceptions on matters of all dimension, varying from small, entertainment tidbits to wide-ranging world affairs. This research examines how the New York Times framed the keywords “Muslim” and “Islam” before and after the 9/11 attacks. Qualitative and quantitative content analyses were used to evaluate articles published 30-days before and after 9/11/2001. The objectives of this research were to explore media depictions and framing techniques employed by the New York Times along with analyzing and comparing descriptive text surrounding the words Islam and Muslim.

Exigence, Audience, Constraints

In “How To Read Social Movement Rhetorics as Discursive Events,” Gerald Biesecker-Mast suggests three specific contexts that readers must take into account when studying social-movement rhetorics, which are helpful for our contextual analyses:

Exigence

First, the critic must describe the specific historical exigence that makes possible a movement rhetoric, and how that exigence is constituted as an unacceptably desperate and unnecessarily existent need. The critic will seek to understand how this event or circumstance comes to exceed the logic whereby the status quo had previously been understood as acceptable. In so doing, the critic must be attentive to the constitutive hope that defines the future for the movement, the imagined state of affairs in which the exigence would be missing and the movement’s goal(s) accomplished. Considering that there may be numerous exigences that create identification with a movement, the critic should look for a “controlling exigence” that comes to function as a “nodal point” of a resistant discourse — as that central element that gives meaning to other subsidiary concerns. Since the hegemonic formation that constitutes the status quo will also be organized around a nodal point, the critic should give attention to rhetorical strategies used by the movement to dislocate the nodal point for the status quo.

Audience

Second, the rhetorical critic should show how a movement rhetoric constitutes its audience as an oppressed or threatened people that is established over and against an oppressing or threatening people or institution. To do so will require attention to the myths and narratives that provide the basis for continuity with a specific past. Such analysis should explain how these narratives are invoked and/or rewritten so as to vindicate the movement’s actions in the present and to invest the audience with a collective identity. Most importantly the critic will seek to understand the means whereby previously acceptable differences between the oppressor and the oppressed are subverted and turned into an unresolved antagonism that comes to constitute the basis of the audience’s identity or, conversely, how harmful social antagonisms (such as racism, sexism, homophobia, etc) are disengaged for the sake of plurality and difference (and thus justice).

Constraints

Thirdly, critics will attend to the specific conditions of possibility for the emergence of an articulating subject, a rhetor (or rhetors) capable of rhetorically rearranging the elements of a social discourse so as to produce a movement whose constituents are opposed to a specific aspect of the status quo. Among these constraints will be the availability to rhetor-leaders of educational and ideological resources for critique, useable traditions of socialization, and media outlets for message dissemination. Additionally, the critic will need to consider what specific forms of ethos can render legitimate a rhetor’s effective constitution in popular rhetoric of a movement-producing chain of equivalences or collection of differences.

Can you characterize generations?

We might have an opportunity this week to explore some characteristics of the millennial generation (PDF), and how your generation is represented in the New York Times.

Started at the Bottom

May 10, 2013Good morning!

At Starbucks, 5:45 a.m., trying to educate myself like a good citizen, and I encounter this:

NYT: Profiles in Science: “A Sense of Where You Are”

“Both of us come from nonacademic families and nonacademic places,” Edvard said. “The places where we grew up, there was no one with any university education, no one to ask. There was no recipe on how to do these things.”

“And how to act politely,” May-Britt interjected.

Labor news in the WSJ and in the NYT

Since the labor and jobs report was released on Friday (technically known as “Employment Situation Summary” from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics), the New York Times has published three similar articles — with some conflicting data, and with necessary reading between the lines:

- “The Idled Young Americans”

- “Life Is O.K., if You Went to College”

- “College Graduates Fare Well in Jobs Market, Even Through Recession”

This might be a good issue for us to discuss this week.

Remember talking about our initial, pre-revision “B.S.” opening sentences?

April 30, 2013Paragraph for close reading: a contextual analysis

It’s also a good case study in the integration of sources and quotes:

Every wolf in Yellowstone therefore is more than just a wolf. Imbued with profound symbolic meaning, each wolf embodies the divergent goals of competing social movements involved in the reintroduction debate. Framed by environmentalists and their wise use opponents as another line in the sand in their ongoing battle for the heart and soul of the West, wolf reintroduction is a high-stakes political conflict. Wolf recovery is often portrayed by environmentalists as being symptomatic of a culture in transition–an inevitable change (Askins, 1995). It is an image that plays especially well with the media: “[T]he wolf issue pits the New West against the Old West” (Johnson, 1994, p. 12), a milestone in the “transformation of power” from the Old West (Brandon, 1995, p.8). Wolf restoration clearly represents change, but sound bites that reduce the social struggle over wolves to an “inevitable” transition from the old to the new are inadequate. They do not explain the underlying social issues driving the transformation. They do not capture the essence of social negotiation, the give-and-take of political exchange between social movements struggling to define the western landscape. Nor do they acknowledge that these social issues will remain after the wolf controversy has exited the center stage of public policy discourse.

Wilson, Matthew. “The Wolf in Yellowstone: Science, Symbol, or Politics? Deconstructing the Conflict between Environmentalism and Wise Use.” Society & Natural Resources. 10(1997): 453-468.

Another example of a contextual analysis in action

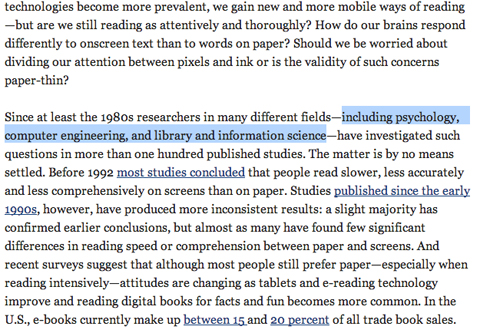

This time, from an article that many of us read and used in our Print & Digital Literacy Projects: “The Reading Brain in the Digital Age: The Science of Paper versus Screens” (Scientific American, April 2013)

How Writers Interact With the World

“The image has been handed down throughout the long iconography of the West, most effectively transmitted in the image of Saint Jerome: the writer as a recluse, weaving spirited collocations of words in hushed seclusion. Jerome may have a lion at his feet, but he lacks other company — and, of course, he has no Wi-Fi. His condition is distinctly different from that of the modern writer; her room is not only well-lighted and likely lion-free, but also furnishes an Internet connection, through which the world’s tumult pours.”

NYT Draft Column (on writing): “How Writers Interact With the World.”

Illustration by Chloé Poizat, whose work I also recommend you get to know.

Text in Context

This artist represents context in a remarkably similar way that we discussed our Text-in-Context projects the other day: “A range of views that argue that a phenomenon can only be properly understood within the context it occurred.” See more here: Minimalist Postcards Merge Philosophy with Graphic Design.

“The Confidence Questions”

“My perception in college was that more men were seminar baboons — dominating the discussions whether they had done the reading or not. But now, when I visit college classes, the women seem just as assertive as the men.”

David Brooks, “The Confidence Questions” 4/22/2013

“There’s so much more I wanted to cover, including the etymology of the word ‘deadline'”

“Workers who fail to meet deadlines risk the disapproval — and sometimes the wrath — of their managers and colleagues.”

“Still, some people will blow a deadline, rationalizing that there is both a “deadline” and a “real deadline.” They  will use whatever devices and excuses they can muster to buy more time.”

will use whatever devices and excuses they can muster to buy more time.”

“But what about assignments that don’t have clear deadlines? Or projects that are so large that they must be done in increments, so that pulling an all-nighter isn’t an option? Or creative goals that no one much cares about, except you?”

“I know people who, through boundless narcissism, single-minded obsession or unfathomable self-discipline can complete big projects without deadlines. Many of us, though, need a looming threat to finish major work.”

Chicago through the lens of a NYT Book Review essay

“… but Dyja zooms in on the qualities Chicagoans value and does it better than anyone else I’ve read: informality; the desire to be “regular”; the conviction among artists that “the process was as important as the product.” These attributes created hospitable conditions for such distinctive genres as Modernist architecture, storefront theater, improv comedy, poetry slams, oral history (perfected by the city patron saint Studs Terkel) and outsider art, even as they alienated writers and artists interested in more than functionality and social reform. Saul Bellow complained about the lack of cafes. “There were greasy-spoon cafeterias, one-arm joints, taverns. I never yet heard of a writer who brought his manuscripts into a tavern.”

New York Times Book Review: Chicago Manuals

‘The Third Coast,’ by Thomas Dyja, and More

Literacy events and literacy practices

Literacy events and literacy practices are key to understanding literacy as a social phenomenon.

Literacy events serve as concrete evidence of literacy practices. Heath (1982) developed the notion of literacy events as a tool for examining the forms and functions of oral and written language. She describes a literacy event as “any occasion in which a piece of writing is integral to the nature of participants’ interactions and their interpretive processes” (p. 93). Any activity in which literacy has a role is a literacy event. As Barton and Hamilton (2000) describe, “Events are observable episodes which arise from practices and are shaped by them. The notion of events stresses the situated nature of literacy, that it always exists in a social context” (p. 8).

Barton and Hamilton (2000) describe literacy practices as “the general cultural ways of utilizing written language which people draw upon in their lives. In the simplest sense literacy practices are what people do with literacy” (p. 8). Literacy practices involve values, attitudes, feelings, and social relationships. They have to do with how people in a particular culture construct literacy, how they talk about literacy and make sense of it. These processes are at the same time individual and social. They are abstract values and rules about literacy that are shaped by and help shape the ways that people within cultures use literacy. Street (1993) described literacy practices, which are inclusive of literacy events, as “‘folk models’ of those events and the ideological preconceptions that underpin them” (pp. 12-13).

One way to get some perspective.

April 19, 2013If you missed class Wednesday, some notes for you:

- We agreed and voted on the course contract, which means that, if you missed class, you’ll need to print this out, sign it, and bring it to my office hours or scheduled conference

- We discussed our NYT Print/Digital Literacy Projects, especially criteria for high-quality, compelling, successful, audience-based projects and how that criteria maps consistently across majors, disciplines, and writing projects in other classes:

[1] The ability to identify questions and find potential, credible sources; how you evaluate and synthesize the information that you find; and how you communicate your findings.

[2] Establishing credibility — how you can guarantee that you’ll be taken seriously: we can tell this writer has had her head in the NYT for 21 days — intensely — and she can generate new meanings in this project because of it.

[3] Practicing audience-based and rhetorical revising, editing, and proofreading. In our case, on this project:

Yesterday: revising

Next Monday: editing

Next Wednesday: proofreading

How do we approach text?

“… how do we approach text? Do we read linearly (from start to fi nish), or do we seek out snippets (using a table of contents, an index, or the “Find” function for searching an online text)? Do we skim or engage in “deep” reading? Do we read quickly or slowly? Answers to these questions are oft en shaped by the character of the text. Is the material familiar or new to the reader? How complex are the words, the syntax, and the concepts? Functionality is also a consideration in de fining reading (reading for information, for conceptual understanding, for enjoyment, or to kill time), as is the physical medium (a scroll, a paperback, an iPhone).”

— Naomi Baron, “Redefining Reading: The Impact of Digital Communication Media.”

101 years ago

April 16, 2013An example of conflicting claims

- Can our Print & Digital Literacy projects help to adjudicate conflicting claims such as these?

- Is there a third side to the issue that people are not considering?

- In our transition from text to context, how can we identify the relevant contexts?

From “The Future of Reading: Literacy Debate: Online, R U Really Reading?” New York Times, July 27, 2008

Thanks, Student Center Mailroom Staff!

April 12, 2013Sample Letter to the Editor

April 11, 2013Brainstorming NYT Print & Digital Literacy Projects

We reviewed our NYT Print and Digital Literacy Projects in class today:

Initial, no-obligation brainstormed ideas. As you read through these, try keeping this WRD103 reflection (WQ 2013) in the back of your mind:

One unanticipated outcome of the project was learning about the extent to which reading is a social practice. We take for granted that writing is a social and civic activity, but many of us had not considered the effects of reading as a private, individual act made public, collective, and collaborative in some contexts, such as ours.

- Do you have a “deep-reading” brain? How do you know?

- Take a position: NYT print or digital? Use credible sources to support your claim(s)

- Choose an article and read it on three different platforms: print, digital, and mobile. Report on your reading experiences. This process will allow you to compare and contrast your experience with claims made about serendipity, annotation, and comprehension

- Rachel (11:20 section) is thinking of creating video interviews of students on campus regarding print and digital reading practices and preferences

- Brian (11:20 section) mentioned that he prefers digital textbooks over conventional print textbooks, which might put him in the minority. (A second source here claims that “Students Find E-Textbooks ‘Clumsy’ and Don’t Use Their Interactive Features.”) Can he use that preference to make a similar argument for reading the NYT in digital formats?

- “Half seriously, is there a booklet on “How to Read the Digital Times”? Can you create a booklet for Mr. Fejes?

- Louise Rosenblatt’s efferent and aesthetic reading practices: can you work with those concepts? Rosenblatt proposed these terms for reading in

1978; have reading practices changed since then?

1978; have reading practices changed since then? - Can you work the serendipity or annotation angles?

- What is the current research-based empirical thinking regarding print and digital reading in terms of resolution, comprehension, attention, and memory?

- Do you feel like you might have more power and control over your reading with the NYT versus, say, a conventional textbook? If so, is some of that power and control taken away when you are limited to reading in specific formats? If you answered “yes” to both, solve that problem.

- Can you respond to the problem and project counter-intuitively, creatively, and without words?

- Are print readers missing out on NYT interactive and multimedia features? What does “reading” look like at this point early in the 21st century?

- What can we learn from your comparison, contrast, and analysis of some of the different NYT Skimmer versions?

- “How a Theater Major Reads the New York Times” report might be interesting, or “How a Business Major Reads the New York Times,” as we would get insights into your reading practices and contextual issues surrounding serendipity, annotation, and comprehension

- If none of these appeal to you, which seems unlikely, review the range of NYT digital platforms here, and develop your own ideas.

Letters to the NYT Editor

In preparation for your Letters to the Editor, we will read several over the next couple of weeks in order to study and analyze the conventions and requirements. Begin with recent responses to David Brooks’s “The Practical University”:

Possible discussion topic for this week

April 8, 2013A Well Cultivated Critical Thinker …

- Raises vital questions and problems, formulating them clearly and precisely;

- Gathers and assesses relevant information, using abstract ideas to interpret it effectively comes to well-reasoned conclusions and solutions, testing them against relevant criteria and standards;

- Thinks openmindedly within alternative systems of thought, recognizing and assessing, as need be, their assumptions, ideologies, implications, and practical consequences; and

- Communicates effectively with others in figuring out solutions to complex problems.

Critical thinking is, in short, self-directed, self-disciplined, self-monitored, and self-corrective thinking. It presupposes assent to rigorous standards of excellence and mindful command of their use. It entails effective communication and problem solving abilities and a commitment to overcome our native egocentrism and sociocentrism. – Adapted from Richard Paul and Linda Elder, The Miniature Guide to Critical Thinking Concepts and Tools, Foundation for Critical Thinking Press, 2008

“A persistent effort to examine any belief or supposed form of knowledge in the light of the evidence that supports it and the further conclusions to which it tends.” Edward M. Glaser. An Experiment in the Development of Critical Thinking. 1941.

“We are what we find, not what we search for.”

– Piero Scaruffi

Welcome to WRD104 — Spring Quarter, 2013

In WRD 104 we focus on the kinds of academic and public writing that use materials drawn from research to shape plausible conclusions based on supportable facts and convincing, defensible arguments. As the second part of the two-course sequence in First Year Writing, WRD 104 continues to explore relationships between writers, readers, and texts in a variety of technological formats.

You’ll be happy to note, I hope, that we build on your previous knowledge and experiences; that is, we don’t assume that you show up here a blank slate. We assume that you have encountered interesting people, have engaging ideas, and have something to say. A good writing course should prepare you to take those productive ideas into other courses and out into the world, where they belong, and where you can defend them and advocate for them.

If you have a project from another course that you would like to continue, or a community project that would benefit from rigorous research, or a professional aspiration that needs research-based support, this is the course for you.

WRD 104 has the following learning outcomes:

Rhetorical Knowledge, which includes focusing on defining purposes, audiences, and conventions

Rhetorical Knowledge, which includes focusing on defining purposes, audiences, and conventions

Critical Thinking, Reading, and Writing, which emphasizes writing and reading for inquiry, thinking, and communicating; finding, analyzing, and synthesizing appropriate primary and secondary sources; exploring relationships among language, knowledge, and power

Critical Thinking, Reading, and Writing, which emphasizes writing and reading for inquiry, thinking, and communicating; finding, analyzing, and synthesizing appropriate primary and secondary sources; exploring relationships among language, knowledge, and power

Composing Processes, which includes practice in using multiple drafts to create and complete a rhetorically appropriate audience-based text and the collaborative and social aspects of writing processes

Composing Processes, which includes practice in using multiple drafts to create and complete a rhetorically appropriate audience-based text and the collaborative and social aspects of writing processes

Knowledge of Conventions, in which we employ a variety of genre and rhetorical conventions in order to appeal to a variety of readers and audiences

Knowledge of Conventions, in which we employ a variety of genre and rhetorical conventions in order to appeal to a variety of readers and audiences

You can read the First Year Writing Learning Outcomes in more detail here.

Your digital portfolio

This is a portfolio-based course, which means that you will collect, organize, reflect on, and showcase your work at the end of the quarter in a digital portfolio format.

As a DePaul student, you will be able to keep your portfolio and have access to it during your time here and after you graduate, as alumni. I mention this now because we can take the time to think about, and to work on, different purposes and audiences for our portfolios: for colleagues, classmates, instructors — academic purposes — and for creative, professional, career, and non-academic purposes and audiences.

Writing Center

Finally, it’s no secret around here that students who take early and regular advantage of DePaul’s Center for Writing-based Learning not only do better in their classes, but also benefit from the interactions with the tutors and staff in the Center.