ask a new question and you will learn new things

“One purpose of a liberal arts education is to make your head a more interesting place to live inside of for the rest of your life.” —Mary Patterson McPherson, President, Bryn Mawr College

“I thought that the future was a place—like Paris or the Arctic Circle. The supposition proved to be mistaken. The future turns out to be something that you make instead of find. It isn’t waiting for your arrival, either with an arrest warrant or a band; it doesn’t care how you come dressed or demand to see a ticket of admission. It’s no further away than the next sentence, the next best guess, the next sketch for the painting of a life’s portrait that may or may not become a masterpiece. The future is an empty canvas or a blank sheet of paper, and if you have the courage of your own thought and your own observation, you can make of it what you will.” —Lewis Lapham

“It ain’t where ya from, it’s where ya at!” —KRS-ONE, Ruminations

“The Times has no intention of altering its coverage to meet the demands of any government — be it that of China, the United States or any other nation. Nor would any credible news organization. The Times has a long history of taking on the American government, from the publication of the Pentagon Papers to investigations of secret government eavesdropping.

“The Times’s commitment is to its readers who expect, and rightly deserve, the fullest, most truthful discussion of events and people shaping the world.”

Editorial: “A Response to President Xi Jinping”

“Writing in the digital age increasingly requires remixing, that is, the transformative reuse and redistribution of existing material for new contexts and audiences. Creation, innovation, and invention in the digital age demand that information be widely shared and widely reused; digital writing practices require ‘plagiarism’ (in some sense).” “Remixing — or the process of taking old pieces of text, images, sounds, and video and stitching them together to form a new product — is how individual writers and communities build common values; it is how composers achieve persuasive, creative, and parodic effects. Remix is perhaps the premier contemporary composing practice.” — DeVoss & Ridolfo, “Composing for Recomposition: Rhetorical Velocity and Delivery,” 2009. Examples for class:

“Writing in the digital age increasingly requires remixing, that is, the transformative reuse and redistribution of existing material for new contexts and audiences. Creation, innovation, and invention in the digital age demand that information be widely shared and widely reused; digital writing practices require ‘plagiarism’ (in some sense).” “Remixing — or the process of taking old pieces of text, images, sounds, and video and stitching them together to form a new product — is how individual writers and communities build common values; it is how composers achieve persuasive, creative, and parodic effects. Remix is perhaps the premier contemporary composing practice.” — DeVoss & Ridolfo, “Composing for Recomposition: Rhetorical Velocity and Delivery,” 2009. Examples for class:

From a profile of Heidi Nelson Cruz in the New York Times:

By the time she arrived at Claremont McKenna College, friends and professors knew her as a whip-smart economics and international relations double-major who would graduate Phi Beta Kappa and a driven and ambitious young woman who was already planning a professional career.

In Mr. Cruz, friends and colleagues say, she finally met not just her match, but also her intellectual equal.

“Heidi is a synthesizer, whereas Ted tends to blow ahead on one line of reasoning,” said Lawrence B. Lindsey, the chief economic adviser on Mr. Bush’s 2000 campaign. Mrs. Cruz pulled together “different points of view,” he said, and Mr. Cruz is “more of a hard-charger on one point of view.”

From the OED:

Sense 6. a. In wider philosophical use and generally: The putting together of parts or elements so as to make up a complex whole; the combination of immaterial or abstract things, or of elements into an ideal or abstract whole. (Opposed to analysis.) Also, the state of being put so together.

From your St. Martin’s Guide:

When you read and interpret a source—for example, when you consider its purpose and relevance, its author’s credentials,its accuracy, and the kind of argument it is making—you are analyzing the source. Analysis requires you to take apart something complex (such as an article in a scholarly journal) and look closely at the parts to understand the whole better.

For academic writing you also need to synthesize—group similar pieces of information together and look for patterns—so you can put your sources (and your own knowledge and experience) together in an original argument. Synthesis is the flip side of analysis: you already understand the parts, so your job is to assemble them into a new whole. [see 3.12e — Synthesizing sources — for examples.]

Related to our discussions about critical thinking, via David Brooks:

Epistemology is the study of how we know what we know. Epistemological modesty is the knowledge of how little we know and can know.

Epistemological modesty is an attitude toward life. This attitude is built on the awareness that we don’t know ourselves. Most of what we think and believe is unavailable to conscious review. We are our own deepest mystery.

Not knowing ourselves, we also have trouble fully understanding others… Not fully understanding others, we cannot get to the bottom of circumstances… Not fully understanding others, we also cannot really get to the bottom of circumstances. No event can be understood in isolation from its place in the historical flow.

And yet this humble attitude doesn’t necessarily produce passivity. Epistemological modesty is a disposition for action. The people with this disposition believe that wisdom begins with an awareness of our own ignorance.

The modest disposition begins with the recognition that there is no one method for solving problems. It’s important to rely on the quantitative and rational analysis. But that gives you part of the truth, not the whole. (245-46)

From Brooks’s book, The Social Animal (2012); also as a TED Talk.

Epistemological modesty applied to politics, policy, and President Obama:

Readers of this column know that I am a great admirer of Barack Obama and those around him. And yet the gap between my epistemological modesty and their liberal worldviews has been evident over the past few weeks. The people in the administration are surrounded by a galaxy of unknowns, and yet they see this economic crisis as an opportunity to expand their reach, to take bigger risks and, as Obama said on Saturday, to tackle every major problem at once.

[…]

If Obama is mostly successful, then the epistemological skepticism natural to conservatives will have been discredited. We will know that highly trained government experts are capable of quickly designing and executing top-down transformational change. If they mostly fail, then liberalism will suffer a grievous blow, and conservatives will be called upon to restore order and sanity.

It’ll be interesting to see who’s right. But I can’t even root for my own vindication. The costs are too high. I have to go to the keyboard each morning hoping Barack Obama is going to prove me wrong.

From Brooks’s Op-Ed, “The Big Test” (2009)

Recent inventions and business methods call attention to the next step which must be taken for the protection of the person, and for securing to the individual what Judge Cooley calls the right “to be let alone.” Instantaneous photographs and newspaper enterprise have invaded the sacred precincts of private and domestic life; and numerous mechanical devices threaten to make good the prediction that “what is whispered in the closet shall be proclaimed from the house-tops.” (195)

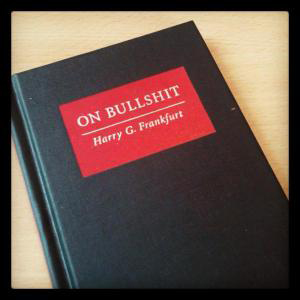

“One of the most salient features of our culture is that there is so much bullshit. Everyone knows this. Each of us contributes his [or her] share. But we tend to take the situation for granted. Most people are rather confident of their ability to recognize bullshit and to avoid being taken in by it. So the phenomenon has not aroused much deliberate concern, or attracted much sustained inquiry.

“One of the most salient features of our culture is that there is so much bullshit. Everyone knows this. Each of us contributes his [or her] share. But we tend to take the situation for granted. Most people are rather confident of their ability to recognize bullshit and to avoid being taken in by it. So the phenomenon has not aroused much deliberate concern, or attracted much sustained inquiry.

In consequence, we have no clear understanding of what bullshit is, why there is so much of it, or what functions it serves.” (p1)

” … she is not concerned with the truth-value of what she says. That is why she cannot be regarded as lying; for she does not presume that she knows the truth, and therefore she cannot be deliberately promulgating a proposition that she presumes to be false: Her statement is grounded neither in a belief that it is true nor, as a lie must be, in a belief that it is not true. It is just this lack of connection to a concern with truth — this indifference to how things really are — that I regard as of the essence of bullshit.” (p10) (more…)

RECENTLY, Senator Kirsten Gillibrand of New York said that if we want to fix the gridlock in Congress, we need more women. Women are more focused on finding common ground and collaborating, she argued. But there’s another reason that we’d benefit from more women in positions of power, and it’s not about playing nicely.

Neuroscientists have uncovered evidence suggesting that, when the pressure is on, women bring unique strengths to decision making.

Alternatives to “society”?

From Kristof, When Whites Just Don’t Get It, Part 3

Imagine that you enter a parlor. You come late. When you arrive, others have long preceeded you and they are engaged in a heated discussion, a discussion too heated for them to pause and tell you exactly what it is about. In fact, the discussion had already begun long before any of them got there, so that no one present is qualified to retrace for you all the steps that had gone before. You listen for a while, until you decide that you have caught the tenor of the argument; then you put in your oar. . . . The discussion is interminable. The hour grows late, and you must depart. And you do depart, with the discussion still vigorously in progress.” — Kenneth Burke

The story language philosopher and rhetorical theorist Kenneth Burke tells is one that is no doubt familiar to you: it describes what most of us feel like when we go to college, begin a major, take on a new job, or enter into any new field. We have to listen hard and then slowly, slowly we begin to understand the conversation going on around us. And eventually we begin to participate—what Burke calls dipping our own oars into the conversation. Learning to write in college is just like that: at first academic writing can seem foreign—stilted and hard to read, even harder to write. Yet paying close attention to how that writing works—to its conventional structures and styles, to its uses of support, to its typical genres and media—will eventually begin to make sense. And with careful instruction and practice, you will enter the “parlor” of academic writing and grow more and more comfortable participating in it.

Practicing writing with precision, clarity, and grace at the same time that you learn how to write most appropriately for different audiences and situations will serve you well in your academic writing and in other areas of your life.

Adapted from Andrea Lunsford.

“I tell college students that by the time they sit down at the keyboard to write their essays, they should be at least 80 percent done. That’s because ‘writing’ is mostly gathering and structuring ideas.” David Brooks, December 30, 2013 NYT.

To convince and persuade

* –> usually a conventional, thesis-driven essay with an identifiable thesis, intro, body, conclusion, like the example in your St. Martin’s Handbook

More often than not, out-and-out defeat of another — as in a debate, for example — is not only unrealistic but also undesirable. Rather, the goal is to persuade readers to see an issue in a particular way, or to help them understand, or move them toward some action, or to cause them to be newly interested in your issue.

To reach a decision or explore an issue: an exploratory essay

* –> this is where we get to see the writer struggling with an issue and engaging in truth-seeking behavior

Often, a writer must enter into conversation with others and collaborate in seeking the best possible understanding of a problem, exploring all possible approaches and choosing the best alternatives. As all good critical thinkers know, there’s always more than just one side of the story, there’s always more than two sides of the story: there’s always a third side of the story. Some people phrase that as “there’s your truth, there’s my truth, and then there’s the real truth.”

To change yourself

* –> we can think of this one as the “Leslie Jameson model”

Sometimes you will find yourself arguing primarily with yourself, and those arguments often take the form of intense meditations on a theme, or even of prayer. In such cases, you may be hoping to transform something in yourself or to reach peace of mind on a troubling subject.

If you’re visiting the Writing Center, make sure you show them these, so that they know what we’re up to.

Something to consider as we think about our Op-Ed essays this week:

“A speaker persuades an audience by the use of stylistic identifications; the act of persuasion may be for the purpose of causing the audience to identify itself with the speaker’s interests; and the speaker draws on identification of interests to establish rapport between herself or himself and the audience.” — Kenneth Burke, A Rhetoric of Motives.

Identification, Burke reminds us, occurs when people share some principle in common — that is, when they establish common ground. Persuasion should not begin with absolute confrontation and separation but with the establishment of common ground, from which differences can be worked out. Imagining common ground is the point of our work with stasis and with exigency.

The book’s theme, “a young woman’s desire for a substantial, rewarding, meaningful life,” was “certainly one with which Eliot had been long preoccupied. . . . And it’s a theme that has made many young women, myself included, feel that ‘Middlemarch’ is speaking directly to us. How on earth might one contain one’s intolerable, overpowering, private yearnings? Where is a woman to put her energies? How is she to express her longings? What can she do to exercise her potential and affect the lives of others? What, in the end, is a young woman to do with herself?”

NYT Book Review/Joyce Carol Oates: “Deep Reader: Rebecca Mead’s ‘My Life in Middlemarch’”

“Evolution is always a trade-off, but for the giraffe the feeding advantages that came with elongation clearly outweighed any diminution in reflex speed. No need to run when you can be a quiet poem masked by a tree.”

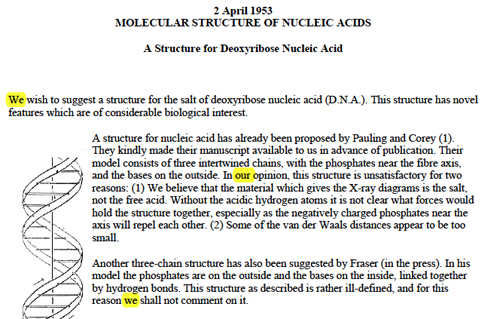

It seems to me that if it was good enough for Watson & Crick — they discovered the molecular structure of DNA, the Double Helix — it’s good enough for you:  Watson, J. D., & Crick, F. H. C. (1953) A structure for deoxyribose nucleic acid (DNA). Nature 171, 737–738.

Watson, J. D., & Crick, F. H. C. (1953) A structure for deoxyribose nucleic acid (DNA). Nature 171, 737–738.

“And at the beginning of a sentence? During the 19th century, some schoolteachers took against the practice of beginning a sentence with a word like but or and, presumably because they noticed the way young children often overused them in their writing. But instead of gently weaning the children away from overuse, they banned the usage altogether! Generations of children were taught they should ‘never’ begin a sentence with a conjunction. Some still are.

“There was never any authority behind this condemnation. It isn’t one of the rules laid down by the first prescriptive grammarians. Indeed, one of those grammarians, Bishop Lowth, uses dozens of examples of sentences beginning with and. And in the 20th century, Henry Fowler, in his famous Dictionary of Modern English Usage, went so far as to call it a ‘superstition.’ He was right. There are sentences starting with And that date back to Anglo-Saxon times.”

— David Crystal, The Story of English in 100 Words. St. Martin’s Press, 2012.

Let’s expand our thinking and use of rhetorical précis:

At one time or another, we have all observed self-regulated learners. They approach educational tasks with confidence, diligence, and resourcefulness. Perhaps most importantly, self-regulated learners are aware when they know a fact or possess a skill and when they do not. Unlike their passive classmates, self-regulated students proactively seek out information when needed and take the necessary steps to master it. When they encounter obstacles such as poor study conditions, confusing teachers, or abstruse textbooks, they find a way to succeed. Self-regulated learners view acquisition as a systematic and controllable process, and they accept greater responsibility for their achievement outcomes. (Zimmerman, 1990.)

The Wikipedia entry on self-regulated learning makes a connection to metacognition.

Great minds discuss ideas.

Average minds discuss events.

Small minds discuss people.

— Eleanor Roosevelt

Life’s prerequisites are courtesy and kindness, the times tables, fractions, percentages, ratios, reading, writing, some history — the rest is gravy, really.

— Nicholson Baker, “Wrong Answer: The Case Against Algebra II”

WRD 103 introduces you to the forms, methods, expectations, and conventions of college-level academic writing. We also explore and discuss how writing and rhetoric create a contingent relationship between writers, readers, and subjects, and how this relationship affects the drafting, revising, and editing of our written — and increasingly digital and multimodal — projects.

In WRD 103, we will:

Finally, it’s no secret around here that students who take early and regular advantage of DePaul’s Center for Writing-based Learning not only do better in their classes, but also benefit from the interactions with the tutors and staff in the Center.

Unclear writing, now as always, stems from unclear thinking–both of which ultimately have political and economic causes.

A well cultivated critical thinker:

Critical thinking is, in short, self-directed, self-disciplined, self-monitored, and self-corrective thinking. It presupposes assent to rigorous standards of excellence and mindful command of their use. It entails effective communication and problem solving abilities and a commitment to overcome our native egocentrism and sociocentrism. – Adapted from Richard Paul and Linda Elder, The Miniature Guide to Critical Thinking Concepts and Tools, 2008.

“A persistent effort to examine any belief or supposed form of knowledge in the light of the evidence that supports it and the further conclusions to which it tends.” Edward M. Glaser. An Experiment in the Development of Critical Thinking. 1941.

Chaffee’s Definition of Critical Thinking

Critical thinkers are people who have developed thoughtful and well-founded beliefs that guide their choices in every area of their lives. In order to develop the strongest and most accurate beliefs possible, you need to become aware of your own biases, explore situations from many different perspectives, and develop sound reasons to support your points of view. These abilities are the tools you need to become more enlightened and reflective “critical thinker” (p. 28).

For Chaffee, critical thinking involves the following:

[From The Thinker’s Way by John Chaffee, Boston: Little, Brown, 1998]