Solentiname is a remote archipelago consisting of 36 islands in the southern area of Lago de Nicaragua, 25 miles from Costa Rica. (You can see Costa Rica’s Rincón de la Vieja active volcano range from Solentiname.) I spend most of my time on Mancarrón—the most populated island with about 33 families and 279 people—and make day trips via canoe to visit students and families on smaller and less-populated San Fernando and La Venada. The islands have no standard electricity sources, cars, or roads. The economy is based largely on subsistence farming and fishing, and there’s a small but active artists’ collective.

My most recent visits have been spent living with community members, teaching ESL and poetry workshops and preparing projects in renewable energy resources. In March I met with faculty and students in the Agricultural Economics Program at La Universidad Paulo Freire in San Carlos, on the mainland about three hours from Solentiname, and gave a presentation on “The Political Economy of Reading and Writing—Literary, Technical, Environmental—In and Around La Reserva Natural de los Guatusos.“ One outcome of that collaboration is a trail redesign and remediation project in a wetlands area of Los Guatusos that I will organize and help lead in the summer of 2013.

My most recent visits have been spent living with community members, teaching ESL and poetry workshops and preparing projects in renewable energy resources. In March I met with faculty and students in the Agricultural Economics Program at La Universidad Paulo Freire in San Carlos, on the mainland about three hours from Solentiname, and gave a presentation on “The Political Economy of Reading and Writing—Literary, Technical, Environmental—In and Around La Reserva Natural de los Guatusos.“ One outcome of that collaboration is a trail redesign and remediation project in a wetlands area of Los Guatusos that I will organize and help lead in the summer of 2013.

Other projects include installing solar panels for both community buildings and for family homes and consulting on the islands’ preparation for an anticipated increase in “eco-tourism,” an issue of pressing concern for technical, cultural, and economic reasons on the islands; some obvious, some not. The people I work with here are rightfully ambivalent about the prospect, so we’re able to work on the planning at a pace dictated by community members. Nicaragua is barely in control of many of its own natural resources, and remote regions such as Solentiname and the Rio San Juan River are sites of increasing global and multinational financial influence. Local community and indigenous rights compete against those less-than-transparent financial initiatives, and part of the current struggle is learning how to protect cultural resources and the community, collective ownership of resources.

“We’re going to decontaminate Lake Nicaragua.

The humans weren’t the only ones who longed for liberation.

The whole ecology had been calling out. The Revolution

also belongs to lakes, rivers, trees, animals.”

— Ernesto Cardenal, from “The New Ecology,” 1979

For example, another summer project is to pilot a biochar plot on one family’s farm. Biochar is a prime candidate for the mitigation of climate change as it replaces the “slash-and-burn” tradition in farming, especially in Central and South America.

If used as the central ingredient of a holistic development approach, biochar soil offers an opportunity to help end hunger among communities at the forest margins; it can also help slow deforestation.

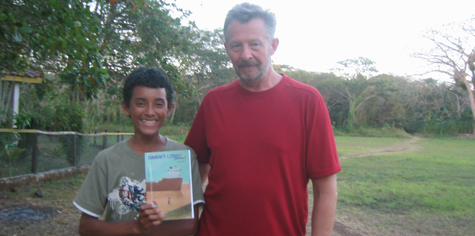

One of the highlights of my most recent trip was delivering copies of the Community Literacy Journal, which I co-edit with John Warnock at the University of Arizona, to three young poets whose work we published in the Spring 2008 issue.

Built in 1966 by Ernesto Cardenal — Jesuit priest and former Nicaraguan Minister of Culture — the church was home to participatory community gospel readings and discussions in the 1960’s and 70’s. Some of the participants of those readings were involved in the first Sandanista military action as citizen revolutionaries against the Somoza regime, in October 1977.

Five community members — three farmers, two fishermen — now considered martyrs in Solentiname, were captured, tortured, and killed; every building and home on the island–except the chapel, which remained undamaged–were destroyed during Somoza’s bombing and destruction in retaliation. This aspect of my community literacy work–working with people who remember this recent history and the power of language that preceded and followed that violent period–often challenges what I know about teaching, but also confirms what I know about people’s capacity to learn from each other and to develop collective expertise.

Regular church services are no longer held here in the church, but poetry workshops are still occasionally conducted by Cardenal during visits from Managua, and I hold most of my workshops and classes there.

Want to help?

An alliance organization that I’ve formed — the Jícaro Collective — to connect students at the University of Central America (UCA) with environmental engineers in Managua and people with whom I work in Solentiname is not soliciting funds at this time, but we do need books in English and in Spanish and computer equipment for students and their parents. If you can help in this way, please let me know: mmoore46@depaul.edu.