Images are more real than anyone could have supposed. And just because they are an unlimited resource, one that cannot be exhausted by consumerist waste, there is all the more reason to apply the conservationist remedy. If there can be a better way for the real world to include the one of images, it will require an ecology not only of real things but of images as well. (Sontag, 1979, p. 180)

What might we mean by an ecology of images? It would be a precarious task to transpose ideas and terminology from the scientific field of ecology, not least because even within the field itself there have been numerous debates over its true focus and distinctiveness. However, as a metaphor for a desire to understand the interrelationships of things (the nature of change, adaptation, and community), the classificatory, comparative, and systems-based approach of ecology can be made pertinent to image studies, as it too seeks to locate how and why images operate in certain ‘environments’ or systems of meaning.

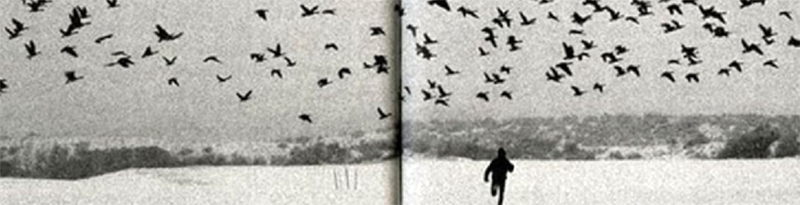

This diagram attempts to plot various terms that might underline an ‘ecology of images’. Taking a cue from the ecologist’s three main ‘units’ of assessment – the organism, its community, and the eco-system – an image always exists in a set of contexts. An image is always part of an ‘image community’, which it works with or against. It is portrayed here with a honeycomb effect around the central image. Image community can be thought of as a genre and/or modality of images. As such, there are formal, aesthetic properties and particular content and uses an image might share with other images, or indeed which it is attempting to work against or appropriate. In addition, the image and its community will always be framed and mediated in specific ways. The square frame in the diagram denotes the presence of an ‘image-system’, which can range across and interconnect with political, economic, technical, cultural, social, and legal discourses and systems. In addition, language and the body provide ways in which we frame, communicate, and comprehend the image.

Another crucial framing of the image is history. Past, present, and future are plotted on the diagram to clearly evoke a sense of process and evolution of the image. The image itself will be formed of certain ‘energies’ or precedents and prior insights, which relate to the fact that an image community and image systems are all historically determined. An image may well be found in great ‘abundance’ (as labeled on the diagram). An advertising image, for example, will clearly be in greater abundance than a child’s drawing made at home one afternoon. Of course, there are various potential futures of the image. The aforementioned child’s drawing might end up the winning entry of a competition; as such, it would likely receive greater distribution (through various means), leading to relative abundance. It may also be re-worked for a final product, which we could understand as the succession of the image. Images can also be adapted. A good example of this would be how cartoonists appropriate images and manipulate them for satirical effect.

Manghani, S. (2013) Image Studies: Theory and Practice. London: Routledge.