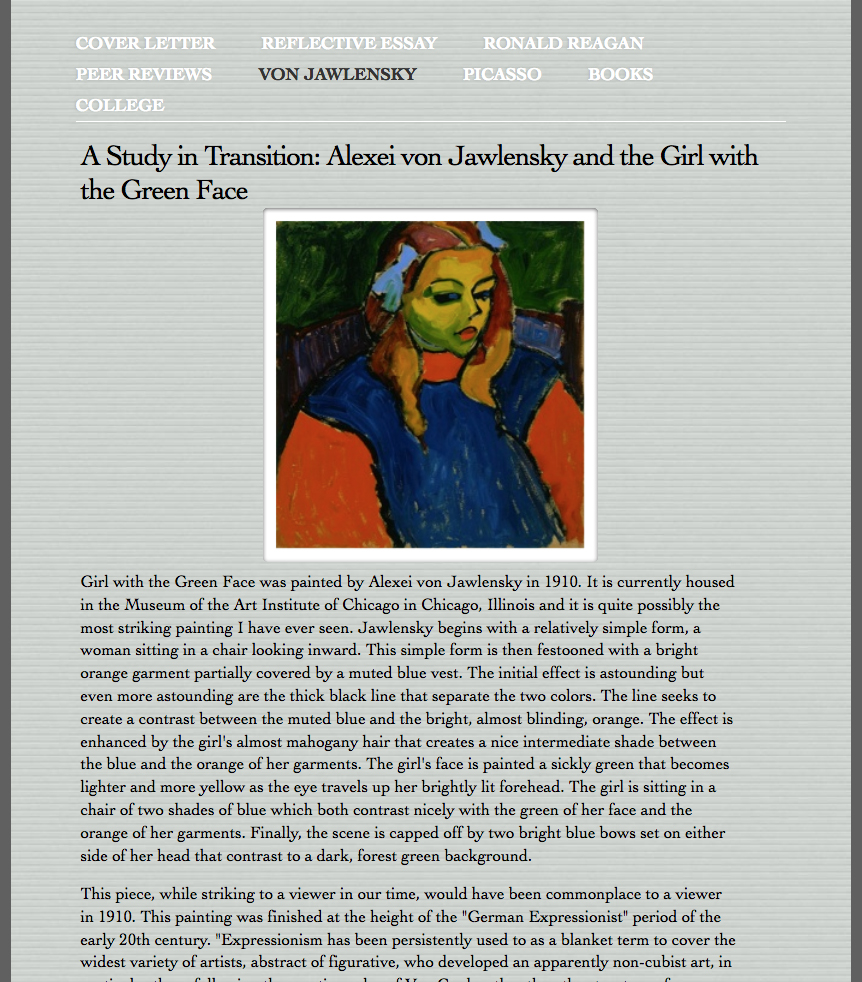

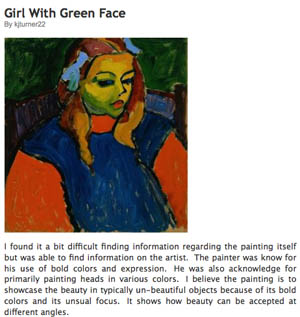

In my WRD103 and 104 courses this year we discussed Alexei Jawlensky’s 1910 painting, Girl With the Green Face as an exercise in textual and contextual analysis, with an eye toward meaning: what does it mean?

The painting seems particularly well suited for that kind of analysis and reflection: its subject is ambiguous (she is, in fact, a girl with a green face); Jawlensky isn’t the most well known of painters, making research that much more difficult; and the painting hangs here in Chicago, at the Art Institute, where, in Gallery 392 in the new Modern Wing, it is surrounded by much more well known artists and paintings.

The painting seems particularly well suited for that kind of analysis and reflection: its subject is ambiguous (she is, in fact, a girl with a green face); Jawlensky isn’t the most well known of painters, making research that much more difficult; and the painting hangs here in Chicago, at the Art Institute, where, in Gallery 392 in the new Modern Wing, it is surrounded by much more well known artists and paintings.

We initially discussed methods of analysis and meaning-making and compared them to the ways we discuss textual artifacts:

- Textual analysis: focusing on textual and visual evidence

- Contextual analysis: considering the circumstances surrounding the composition of a text or painting

- Reader-response analysis: reflecting on our own backgrounds, assumptions, experiences, and ideologies, and how all of that informs to various degrees, our understanding of a text, painting, and meaning-making activities

For comparison, and to integrate some interdisciplinary methods, we also discussed a range of approaches to interpretation, including traditional art history and cultural criticism.

Things got more interesting when—after these initial class discussions on what we thought the “Girl with the Green Face” might mean—students set out to do initial research and to report their finding in rhetorical précis form on their individual WordPress blogs:

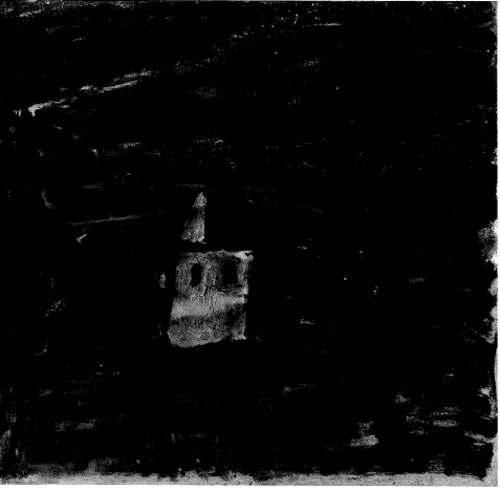

We then visited the Art Institute to see the painting in person, which is always a pleasure, but this time—thanks to the foresight and a couple of calls by a particularly engaged student—we were met by one of the museum’s curators, who is also a researcher. She explained that The Girl with the Green Face had just recently undergone cleaning and, at the same time, an x-ray of the canvas. Behind the painting, on the same canvas, they found a sketch by Jawlensky, of a building:

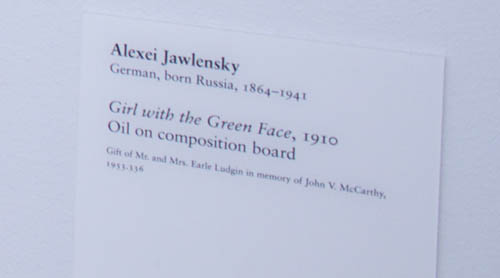

Because museum curators and the research staff had been busy preparing the new, big, Matisse exhibit–this curator barely had time to talk to us, in fact–they had not yet shown the canvas’s x-ray around much. Our class was among the first to see it, and students gained tremendous insights into a painting’s life: its composition, provenance, and its place in the new Modern Wing: off in a corner, surrounded by bigger, more famous artists and their pieces, without much of a gallery label:

And then, not unrelated, toward future iterations of this assignment, from Jeanette Winterson’s Art Objects: Essays on Ecstasy and Effrontery:

Art takes time. To spend an hour looking at a painting is difficult. The public gallery experience is one that encourages art at a trot. There are the paintings, the marvelous speaking works, definite, independent, each with a Self it would be impossible to ignore, if…if…, it were possible to see it. I do not only mean the crowds and the guards and the low lights and the ropes, which make me think of freak shows, I mean the thick curtain of irrelevances that screens the painting from the viewer. Increasingly, galleries have a habit of saying when they acquired a painting and how much it cost…

Millions! The viewer does not see the colours on the canvas, he sees the colour of the money.

- Is the painting famous? Yes! Think of all the people who have carefully spared one minute of their lives to stand in front of it.

- Is the painting Authority? Does the guide-book tell us that it is part of The Canon? If Yes, then half of the viewers will admire it on principle, while the other half will dismiss it on principle.

- Who painted it? What do we know about his/her sexual practices and have we seen anything about them on the television? If not, the museum will likely have a video full of schoolboy facts and tabloid gossip.

- Where is the tea-room/toilet/gift shop?

Where is the painting in any of this?

Experiencing paintings as moving pictures, out of context, disconnected, jostled, over-literary, with their endless accompanying explanations, over-crowded, one against the other, room on room, does not make it easy to fall in love. Love takes time. It may be that if you have as much difficulty with museums as I do, that the only way into the strange life of pictures is to expose yourself to as much contemporary art as you can until you find something, anything, that you will go back and back to see again, and even make great sacrifices to buy. Inevitably, if you start to even make great sacrifices to buy. Inevitably, if you start to love pictures, you will start to buy pictures. The time, like the money, can be found, and those who call the whole business élitist, might be fair enough to reckon up the time they spend in front of the television, at the DIY store, and how much the latest satellite equipment and new PC has cost.

For myself, now that paintings matter, public galleries are much less dispiriting. I have learned to ignore everything about them, except for the one or two pieces with whom I have come to spend the afternoon.

Supposing we made a pact with a painting and agreed to sit down and look at it, on our own with no distractions, for one hour. The painting should be an original, not a reproduction, and we should start with the advantage of liking it, even if only a little. What would we find?

Increasing discomfort. When was the last time you looked at anything, solely, and concentratedly, and for its own sake? Ordinary life passes in a near blur. If we go to the theatre or the cinema, the images before us change constantly, and there is the distraction of language. Our loved ones are so well known to us that there is no need to look at them, and one of the gentle jokes of married life is that we do not. Nevertheless, here is a painting and we have agreed to look at it for one hour. We find we are not very good at looking.

Increasing distraction. Is my mind wandering to the day’s work, to the football match, to what’s for dinner, to sex, to whatever it is that will give me something to do other than to look at the painting?

Increasing invention. After some time spent daydreaming, the guilty or the dutiful might wrench back their attention to the picture.

Increasing irritation. Why doesn’t the picture do something? Why is it hanging there staring at me? What is this picture for? Pictures should give pleasure but this picture is making me very cross. Why should I admire it? Quite clearly it doesn’t admire me…

Admire me is the sub-text of so much of our looking; the demand put on art that it should reflect the reality of the viewer. The true painting, in its stubborn independence, cannot do this, except coincidentally. Its reality is imaginative not mundane.

When the thick curtain of protection is taken away; protection of prejudice, protection of authority, protection of trivia, even the most familiar of paintings can begin to work its power. There are very few people who could manage an hour alone with the Mona Lisa.

But our poor art-lover in his aesthetic laboratory has not succeeded in freeing himself from the protection of assumption. What he has found is that the painting objects to his lack of concentration; his failure to meet intensity with intensity. He still has not discovered anything about him. He is inadequate and the painting has told him so.

It is not as hopeless as it seems. If I can be persuaded to make the experiment again (and again and again), something very different might occur after the first shock of finding out that I do not know how to look at pictures, let alone how to like them.

A favourite writer of mine, an American, an animal trainer, a Yale philosopher, Vicki Hearne, has written of the acute awkwardness and embarrassment of those who work with magnificent animals, and find themselves at a moment of reckoning, summed up in those deep and difficult eyes and for many the gaze is too insistent. Better to pretend that art is dumb, or at least has nothing to say that makes sense to us. If art, all art, is concerned with truth, then a society in denial will not find much in use for it.