Concluding thoughts

“One purpose of a liberal arts education is to make your head a more interesting place to live inside of for the rest of your life.” —Mary Patterson McPherson, President, Bryn Mawr College

“I thought that the future was a place—like Paris or the Arctic Circle. The supposition proved to be mistaken. The future turns out to be something that you make instead of find. It isn’t waiting for your arrival, either with an arrest warrant or a band; it doesn’t care how you come dressed or demand to see a ticket of admission. It’s no further away than the next sentence, the next best guess, the next sketch for the painting of a life’s portrait that may or may not become a masterpiece. The future is an empty canvas or a blank sheet of paper, and if you have the courage of your own thought and your own observation, you can make of it what you will.” —Lewis Lapham

“It ain’t where ya from, it’s where ya at!” —KRS-ONE, Ruminations

Example of Pew Research

- Pew: “Millennials in Adulthood: Detached from Institutions, Networked with Friends”

- Report Infographics — see right-hand column

- Pew Research Center

Portfolios FAQ

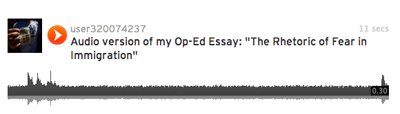

Where should our SoundCloud recording go?

It depends: if you want to use it as part of your reflective, theorizing-myself-as-a-writer essay, you can embed it anywhere in the essay, which would be a really nice touch for the reader. Or, if it doesn’t play an obvious role in your reflective essay, you can include it as part of your Revised Essay & Process Description, probably at the top of that page, where readers can see it.

How do I embed my SoundCloud in Digication?

After you have your SoundCloud URL ready, you’ll have three options:

- Embedded hyperlink

- Large embedded player

- Small embedded player

Read about your three options here.

Why am I recording an audio version of my persuasive essay?

I want to know if you hear anything interesting while listening to yourself while you read your work aloud. As many of you noticed when I read your work aloud in my office, I would sometimes elicit noises from you — “Oh.” “Oops.” “Jeez.” “Wait.” “Ugh.” “Huh.” “Hmmm.” “I didn’t mean it like that …” “I meant it exactly like that …” “Wrong tone. “Right tone.”

What’s going on in those moments? What are you hearing? (You could conceivably milk that for a lot in your reflection, couldn’t you?)

Am I allowed to have a sense of humor while recording my essay?

Yes.

What information do I need to include in my Work Showcase?

Not much. Maybe just a sentence that explains “I have included my final drafts here and link to them from my Reflective Essay. You can read about them there or review them here.”

Compassion, empathy, and reading

11:20 Section Rhetorical Analysis & Conclusions

I Write, Therefore I Am:

A Rhetorical Analysis of David Brooks’s “Engaged or Detached?”

In the New York Times article, “Engaged or Detached?” David Brooks claims that writers need to maintain a detached perspective in order to honestly inform their readers. Brooks defines the differences between a detached writer and an engaged writer as the difference between truth seeking and activism. The goals of an engaged writer are to have a limited “immediate political influence” while detached writers have more realistic goals, aiming to provide a more objective view.

In order to support his claims Brooks uses a variety of rhetorical strategies. For example, he measures the detached writing method against the engaged writing method. Brooks lays out the detached writer’s motivations as the desire to teach or seek out the truth. He then goes on to describe the specific motivations of the engaged writer: energizing the political base, and mobilizing – rather than persuading — the audience that already allies with his ideology.

Brooks’s articles also depends on rhetorical strategies of pathos and logos. The diction triggers emotions while he predominantly employs his logic and reasons to convince his audience. For example, “at his worst, the engaged writer slips into rabid extremism and simple minded brutalism. At her worst, the detached writer slips into a sanguine, pox-on-all-your-houses complacency and an unearned sense of superiority.” His use of “brutalism, extremism, and superiority” evokes an emotional response due to their negative connotation.

Brooks’s own ethos is revealed by writing this article as a detached writer. He encourages writers to stray away from an engaged perspective in order to maintain mental hygiene which is being honest with oneself. “Detached writers generally understand that they are not going to succeed in telling people what to think.” His argument is one for the case of curiosity and humility.

Brooks suggests the style you write can “end up dictating our morals” therefore you are what you write.

9:40 Section Rhetorical Analysis & Conclusions

A Rhetorical Analysis of David Brooks’s “Engaged or Detached?”

Are we engaged or detached as writers? In David Brooks’s article “Engaged or Detached,” he argues that there are moral values associated with both styles of writing. He paints an image of engaged writers as very dedicated and loyal to their causes, and paints detached writers as critical thinkers. Brooks also argues that it’s better to be detached writers but that most writers end up on the engaged end of the spectrum. Throughout the article, Brooks compares and contrasts the two ideological commitments and shows how detached writing can result in more action.

Brooks shapes his argument with a deep sense of ethics. For example, engaged writers use their works merely to justify their own arguments, where detached writers, “spark conversations about underlying concepts, underlying reality and the underlying frame of debate.” Detached writers tend to have more open minds about the arguments they’re making. For example, he shows how a detached writer inhabits truth-seeking behavior in attempt to have an explorative world view, and an engaged writer is focused on the ideology of their affiliations.

Brooks argues for a detached method of writing through writing in a detached ethos himself. He uses a teaching tone rather than an experienced tone, in order to identify with the reader. For example, he seems to treat both styles of writing as equal showing the pros and cons of each ideology. He argues that “engaged writers develop a talent for muzzle velocity, not curiosity” while the detached writer “generally understands that they are not going to succeed in telling people what to think.” He shifts from showing what it means to be each type of writer based on the action it would cause from being that type of writer.

Throughout the article, Brooks shows how one becomes a certain type of writer and therefore, a certain type of person. He shows that how you write not only reflects what kind of person you are, it shapes you as well. For example, throughout the article, Brooks teaches explicitly the differences between engaged and detached writing, and then – as though out of nowhere – he reveals his purpose in writing the article, which is ultimately to comment on the moral framework that each style shows.

Paragraph development, continued: PIE

“[P] This is a triumph of the teen-girl aesthetic approach to the world: that you surround yourself with images that you feel reflect who you are or who you want to be. It used to be derided as narcissistic or derivative, but aesthetic curation is now a widely popular, socially accepted, and venture-backed phenomenon. And while it remains gendered ([I] consider the stereotypes of Pinterest users), the practice of sharing visual influences is gaining popularity so fast that my guess is it won’t be for long. [E] We’re all teen girls now.”

From Ann Friedman, “Our Tumblrs, Our Teenage Selves”

P. A1, above the fold

March 6, 2014Toward Brooks’s conclusion …

We find this interesting paragraph:

“Engaged writers gravitate toward topics where they can do the most damage to the other side. These are topics where the battle lines are clearly drawn, not topics where there is a great deal of uncertainty. Engaged writers develop a talent for muzzle velocity, not curiosity. Just as in life, our manners end up dictating our morals. So, in writing our prose, styles end up shaping our mentalities. If you write in a way that suggests combative certitude, you may gradually smother the inner chaos that will be the source of lifelong freshness and creativity.”

We aren’t the first to inquire …

Live the Questions

“I would like to beg you, as well as I can, to have patience with everything unresolved in your heart and to try to love the questions themselves as if they were locked rooms or books written in a very foreign language. Don’t search for the answers, which could not be given to you now, because you would not be able to live them. And the point is to live everything. Live the questions now. Perhaps then, someday far in the future, you will gradually, without even noticing it, live your way into the answer.”

Rainer Maria Rilke, 1903

in Letters to a Young Poet

Think Critically

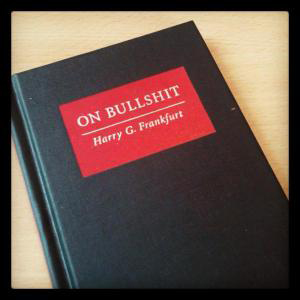

February 28, 2014Bullshit is a process, not a product?

“One of the most salient features of our culture is that there is so much bullshit.  Everyone knows this. Each of us contributes his [or her] share. But we tend to take the situation for granted. Most people are rather confident of their ability to recognize bullshit and to avoid being taken in by it. So the phenomenon has not aroused much deliberate concern, or attracted much sustained inquiry. In consequence, we have no clear understanding of what bullshit is, why there is so much of it, or what functions it serves.” (p1)

Everyone knows this. Each of us contributes his [or her] share. But we tend to take the situation for granted. Most people are rather confident of their ability to recognize bullshit and to avoid being taken in by it. So the phenomenon has not aroused much deliberate concern, or attracted much sustained inquiry. In consequence, we have no clear understanding of what bullshit is, why there is so much of it, or what functions it serves.” (p1)

” … she is not concerned with the truth-value of what she says. That is why she cannot be regarded as lying; for she does not presume that she knows the truth, and therefore she cannot be deliberately promulgating a proposition that she presumes to be false: Her statement is grounded neither in a belief that it is true nor, as a lie must be, in a belief that it is not true. It is just this lack of connection to a concern with truth — this indifference to how things really are — that I regard as of the essence of bullshit.” (p10)

From On Bullshit, Harry Frankfurt.

Frankfurt, Harry G. On Bullshit. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005.

<http://press.princeton.edu/titles/7929.html>

Check your privilege

Click here to check your privilege:

“Check Your Privilege” is an online expression used mainly by social justice bloggers to remind others that the body and life they are born into comes with specific privileges that do not apply to all arguments or situations. The phrase also suggests that when considering another person’s plight, one must acknowledge one’s own inherent privileges and put them aside in order to gain a better understanding of his or her situation. [Know your meme.]

How to pick a boyfriend

“Modern Love: Under His Misspell”: When a writer falls in love with someone whose spelling and grammar are poor, it challenges her assumptions about the type of man she’d want to marry.

From The Onion:

WASHINGTON—Unable to rest their eyes on a colorful photograph or boldface heading that could be easily skimmed and forgotten about, Americans collectively recoiled Monday when confronted with a solid block of uninterrupted text.

Dumbfounded citizens from Maine to California gazed helplessly at the frightening chunk of print, unsure of what to do next. Without an illustration, chart, or embedded YouTube video to ease them in, millions were frozen in place, terrified by the sight of one long, unbroken string of English words.

Hunger Games, continued

“The films of a nation reflect its mentality in a more direct way than other artistic media.”

— Siegfried Kracauer, “From Caligari to Hitler.”

“I’m actually part of this weird wolf pack.”

— Stu Price, “The Hangover Part II.”

After our Hunger Games discussion this week, I looked to see if I could find any scholarly film criticism on our questions and found this:

The Hunger Games is about the first stirrings of revolutionary consciousness, but its relationship to capitalism is less clear than it might initially appear. Does the Capitol double for capital, or is the form of exploitation in The Hunger Games of a cruder type? Although the Capitol looks at first sight like a metropolitan capitalist society, the mode of power at work in Panem is better described as cyber-feudal.

Market signifiers are, after all, strangely absent from the Capitol. Commodities are ubiquitous, but there are no corporate logos, shops, or brand names in the city. So far as we can see, the state, under the beady gaze of President Snow, seems to own everything. It exerts its power directly, via an authoritarian police force of white-uniformed Peacekeepers which inflicts punishment summarily, and symbolically, through the Hunger Games and other rituals in which the districts are required to demonstrate their subordination. In District 12, meanwhile, there is a black market, but little indication of legitimate commercial activity. We know that Peeta works in his parents’ bakery, but the overwhelming impression of District 12 is of a society bent double by manual labor, in which shopping is by no means a leisure activity.

Fisher, Mark.”Precarious Dystopias: The Hunger Games, in Time , and Never Let Me Go.” Film Quarterly. 65 (2012): 27-33. [DePaul Library link]

These are 20th-century numbers

“Now the language of education reform has changed, and the emphasis is on testing, accountability, and order.

“Especially order: increasingly, and in surprising numbers, kids whose behavior subverts efficient learning are medicated so that they and their classmates can keep pace. The United States produces and uses about 90 percent of the world’s Ritalin and its generic equivalents. In 1980 it was estimated that somewhere between 270,000 and 541,000 elementary school students were taking Ritalin. By 1987 around 750,000 were. And the use of the drug didn’t really take off until the 1990s. In 1997 around 30,000 pounds were produced—an increase of more than 700 percent over the 1990 production level.”

[…]

“One senior told me she had subscribed to The New York Times once, but the papers had just piled up unread in her dorm room. “It’s a basic question of hours in the day,” a student journalist told me. “People are too busy to get involved in larger issues. When I think of all that I have to keep up with, I’m relieved there are no bigger compelling causes.”

David Brooks, “The Organization Kid” April, 2001

From the conclusion of “An Actor Who Made Unhappiness a Joy to Watch: A. O. Scott on Philip Seymour Hoffman”

He did not care if we liked any of these sad specimens. The point was to make us believe them and to recognize in them — in him — a truth about ourselves that we might otherwise have preferred to avoid. He had a rare ability to illuminate the varieties of human ugliness. No one ever did it so beautifully.

If you are writing “What is the Purpose of College” Op-Eds, can you use this?

The book’s theme, “a young woman’s desire for a substantial, rewarding, meaningful life,” was “certainly one with which Eliot had been long preoccupied. . . . And it’s a theme that has made many young women, myself included, feel that ‘Middlemarch’ is speaking directly to us. How on earth might one contain one’s intolerable, overpowering, private yearnings? Where is a woman to put her energies? How is she to express her longings? What can she do to exercise her potential and affect the lives of others? What, in the end, is a young woman to do with herself?”

NYT Book Review/Joyce Carol Oates: “Deep Reader: Rebecca Mead’s ‘My Life in Middlemarch’”

The word “testimony” keeps coming up in interesting ways.

NYT: “Testimony of a Cleareyed Witness”

Carrie Mae Weems Charts the Black Experience in Photographs

Essays

“I tell college students that by the time they sit down at the keyboard to write their essays, they should be at least 80 percent done. That’s because ‘writing’ is mostly gathering and structuring ideas.” David Brooks, December 30, 2013 NYT.

The Sidney Awards, Part 1 The Sidney Awards, Part 2

“This year, many of these essays probed the intersection between science and the humanities. Links to all can be found on the online edition of this column.”

Rhetoric & Identification

Something to consider as we think about our Op-Ed essays this week:

“A speaker persuades an audience by the use of stylistic identifications; the act of persuasion may be for the purpose of causing the audience to identify itself with the speaker’s interests; and the speaker draws on identification of interests to establish rapport between herself or himself and the audience.” — Kenneth Burke, A Rhetoric of Motives.

Identification, Burke reminds us, occurs when people share some principle in common — that is, when they establish common ground. Persuasion should not begin with absolute confrontation and separation but with the establishment of common ground, from which differences can be worked out. Imagining common ground is the point of our work with stasis and with exigency.

9a Arguing for a purpose — page 186

To win

The most traditional purpose of academic argument, arguing to win, is used in campus debating societies, in political debates, in trials, and often in business. The writer or speaker aims to present a position that prevails over or defeats the positions of others.

To convince and persuade

More often than not, out-and-out defeat of another is not only unrealistic but also undesirable. Rather, the goal is to convince other persons that they should change their minds about an issue.

To reach a decision or explore an issue

Often, a writer must enter into conversation with others and collaborate in seeking the best possible understanding of a problem, exploring all possible approaches and choosing the best alternative.

To change yourself

Sometimes you will find yourself arguing primarily with yourself, and those arguments often take the form of intense meditations on a theme, or even of prayer. In such cases, you may be hoping to transform something in yourself or to reach peace of mind on a troubling subject.

Does language shape reality?

February 5, 2014Here’s how.

February 4, 2014Brooks on College

— Brooks again: “The Practical University”

— Tugend: “Vocation or Exploration? Pondering the Purpose of College”

Notes for your Rhetorical Analysis

Notes from class yesterday:

Part of this project is getting practice identifying and using the resources available to you, including time management, problem solving, and professional followthrough. In the case of the Rhetorical Analysis project, you have:

- Me! mmoore46@depaul.edu

- Writing Center (and see especially the rhetorical analysis page under “types of writing”)

- St. Martin’s Handbook, chapter 8 on reading & analyzing arguments, especially 8g: A student’s rhetorical analysis of an argument

And then you have some very specific critical reading-and-writing tools in your writing quiver that you can pull out when needed:

Typography and font choices

The size and shape of fonts affects reading and comprehension to a much greater extent than most of us give them credit for — thus making them deeply rhetorical choices. We’ll talk about some of those differences in class and look at examples, including default fonts in your favorite word-processing program and in Digication.

Interesting use of the word “paragraph”

“So these days, Mr. Obama envisions a more modest place in the tide of history. ‘At the end of the day, we’re part of a long-running story,’ he told David Remnick of The New Yorker. ‘We just try to get our paragraph right.'”

Notes on paragraphs & paragraph development

From our St. Martin’s Handbook:

5c: Developing paragraphs

5d: Making paragraphs coherent

5e: Linking paragraphs together

From the NYT article, “How Can We Help Men? By Helping Women”:

[P] Actually, it wouldn’t, because “gender-neutral” work practices and social policies were traditionally based on a masculine model. [I] Employers assumed that there was no need to accommodate caregiving obligations because the “normal” worker had a wife to do that. Policy makers assumed there was no need for universal programs such as family allowances and public child care because the “normal” woman had a husband to support her and her children. [E] Accordingly, most social benefits, such as Social Security and unemployment insurance, were tied to prior participation in the labor market. Welfare was a stigmatized and stingy backup for misfits who were not in a male-breadwinner family.

Nate Silver & Truth-Seeking Behavior

Nate Silver presents his BS-meter — modeled on the old terror alert system — to evaluate information sources and “expertise.”

“Probability is the waystone between ignorance and knowledge. Sometimes the pundit who says ‘I don’t know’ is the one you should trust.”

Chicago on P.1 Again …

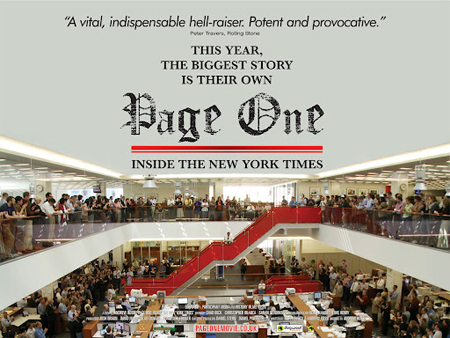

January 23, 2014Background for Page One

- David Carr

- Carr’s “At Flagging Tribune, Tales of a Bankrupt Culture” (the article he’s working on during the filming of Page One)

- Carr on Stephen Colbert, 2008 (just prior to the Page One film) and 2011 (just after)

- Pentagon Papers (via National Archive)

- Pentagon Papers (via NYT)

- Pentagon Papers, P.1, NYT, June 13, 1971

- WikiLeaks

- WikiLeaks on Twitter

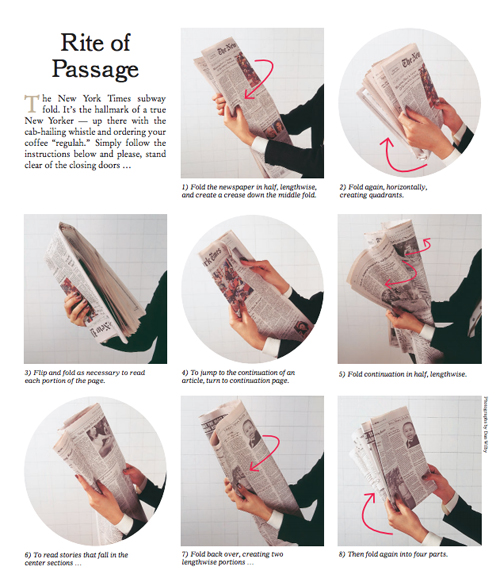

For your Page One reflection:

— What did you learn about the NYT from watching this film?

— What was the most interesting part for you?

— What role do women play in the film?

— What questions, concerns, or ideas does the film raise for you?

As with all good writing, the more specific you can be, the better.

Welcome back!

January 9, 2014Welcome to WRD 103: Rhetoric & Composition

Great minds discuss ideas.

Average minds discuss events.

Small minds discuss people.

— Eleanor Roosevelt

Life’s prerequisites are courtesy and kindness, the times tables, fractions, percentages, ratios, reading, writing, some history — the rest is gravy, really.

— Nicholson Baker, “Wrong Answer: The Case Against Algebra II”

WRD 103 introduces you to the forms, methods, expectations, and conventions of college-level academic writing. We also explore and discuss how writing and rhetoric create a contingent relationship between writers, readers, and subjects, and how this relationship affects the drafting, revising, and editing of our written — and increasingly digital and multimodal — projects.

In WRD 103, we will:

- Gain experience reading and writing in multiple genres in multiple modes

- Practice writing in different rhetorical circumstances, marshaling sufficient, plausible support for your arguments and advocacy positions

- Practice shaping the language of written and multimodal discourses to your audiences and purposes, fostering clarity and emphasis by providing explicit and appropriate cues to the main purpose of your texts

- Practice reading and evaluating the writing of others in order to identify the rhetorical strategies at work in written and in multimodal texts.

- You’ll be happy to note, I hope, that we build on your previous knowledge and experiences; that is, we don’t assume that you show up here a blank slate. We assume that you have encountered interesting people, have engaging ideas, and have something to say. A good writing course should prepare you to take those productive ideas into other courses and out into the world, where they belong, and where you can defend them and advocate for them.

Finally, it’s no secret around here that students who take early and regular advantage of DePaul’s Center for Writing-based Learning not only do better in their classes, but also benefit from the interactions with the tutors and staff in the Center.

A well cultivated critical thinker:

A well cultivated critical thinker:

- Raises vital questions and problems, formulating them clearly and precisely;

- Gathers and assesses relevant information, using abstract ideas to interpret it, effectively comes to well-reasoned conclusions and solutions, testing them against relevant criteria and standards;

- Thinks openmindedly within alternative systems of thought, recognizing and assessing, as need be, their assumptions, ideologies, implications, and practical consequences; and

- Communicates effectively with others in figuring out solutions to complex problems.

Critical thinking is, in short, self-directed, self-disciplined, self-monitored, and self-corrective thinking. It presupposes assent to rigorous standards of excellence and mindful command of their use. It entails effective communication and problem solving abilities and a commitment to overcome our native egocentrism and sociocentrism. – Adapted from Richard Paul and Linda Elder, The Miniature Guide to Critical Thinking Concepts and Tools, Foundation for Critical Thinking Press, 2008

“A persistent effort to examine any belief or supposed form of knowledge in the light of the evidence that supports it and the further conclusions to which it tends.” Edward M. Glaser. An Experiment in the Development of Critical Thinking. 1941.