“Every classroom is an act of making citizens in the realm of that room, and every room is a figure for the larger community.” ~ A. Bartlett Giamatti, A Free and Ordered Space.

ask a new question and you will learn new things

“One purpose of a liberal arts education is to make your head a more interesting place to live inside of for the rest of your life.” —Mary Patterson McPherson, President, Bryn Mawr College

“I thought that the future was a place—like Paris or the Arctic Circle. The supposition proved to be mistaken. The future turns out to be something that you make instead of find. It isn’t waiting for your arrival, either with an arrest warrant or a band; it doesn’t care how you come dressed or demand to see a ticket of admission. It’s no further away than the next sentence, the next best guess, the next sketch for the painting of a life’s portrait that may or may not become a masterpiece. The future is an empty canvas or a blank sheet of paper, and if you have the courage of your own thought and your own observation, you can make of it what you will.” —Lewis Lapham

“It ain’t where ya from, it’s where ya at!” —KRS-ONE, Ruminations

From Brooks, “The Campus Crusaders”

If you’ll allow me to take him out of context for just a moment and replace “settled philosophies” with our terms:

That works for me. Does it work for you?

What kinds of writing make something happen in the world? College students in a six-year research study felt particular pride in the writing they did for family, friends, and community groups—and for many extracurricular activities that were meaningful to them. They produced flyers for fundraising campaigns, newsletters for community action groups, nature guides for local parks, press releases for campus events,and Web sites for local emergency services. Furthermore, once these students graduated from college, they continued to create—and to value—these kinds of public writing.

A large group of college students participating in a research study were asked, “What is good writing?” The researchers expected fairly straightforward answers like “writing that gets its message across,” but the students kept coming back to one central idea: At some point during your college years or soon after, you are highly likely to create writing that is not just something that you turn in for a grade, but writing that you do because you want to make a difference. The writing that matters most to many students and citizens, then, is writing that has an effect in the world: writing that gets up off the page or screen, puts on its working boots, and marches out to get something done!

— St. Martin’s Handbook, 12.66 — page 890.

We’ll add to this in class during Week 10 as needed, in our search for — and our practice of — cognitive vigilance in editing with a goal of visual & logistical coherence:

y not be aware of how we approached, planned, and completed projects. It’s good practice to summarize the assignment and your approach to it.

y not be aware of how we approached, planned, and completed projects. It’s good practice to summarize the assignment and your approach to it.

NYT: Getting It Right

What is it to truly know something? In our daily lives, we might not give this much thought — most of us rely on what we consider to be fair judgment and common sense in establishing knowledge. But the task of clearly defining true knowledge is trickier than it may first seem, and it is a problem philosophers have been wrestling with since Socrates.

“… all the ways corporations and new technologies fiendishly generate new tasks for us — each of them seemingly insignificant but amounting to many hours of annoyance. Examples include deleting spam from our inboxes, installing software upgrades, creating passwords for every website we seek to enter, and periodically updating those passwords. If nothing else, he gives new meaning to the word “distraction” as an explanation for civic inaction. As the seas rise and the air condenses into toxic smog, many of us will be bent over our laptops, filling out forms and attempting to wade through the “terms and conditions.”

“… all the ways corporations and new technologies fiendishly generate new tasks for us — each of them seemingly insignificant but amounting to many hours of annoyance. Examples include deleting spam from our inboxes, installing software upgrades, creating passwords for every website we seek to enter, and periodically updating those passwords. If nothing else, he gives new meaning to the word “distraction” as an explanation for civic inaction. As the seas rise and the air condenses into toxic smog, many of us will be bent over our laptops, filling out forms and attempting to wade through the “terms and conditions.”

Something to consider as we think about our Op-Ed essays this week:

“A speaker persuades an audience by the use of stylistic identifications; the act of persuasion may be for the purpose of causing the audience to identify itself with the speaker’s interests; and the speaker draws on identification of interests to establish rapport between herself or himself and the audience.” — Kenneth Burke, A Rhetoric of Motives.

Identification, Burke reminds us, occurs when people share some principle in common — that is, when they establish common ground. Persuasion should not begin with absolute confrontation and separation but with the establishment of common ground, from which differences can be worked out. Imagining common ground is the point of our work with stasis.

To change yourself (St. Martin’s Handbook: 9a. Arguing for a purpose — page 186)

Sometimes you will find yourself arguing primarily with yourself, and those arguments often take the form of intense meditations on a theme, or even of prayer. In such cases, you may be hoping to transform something in yourself or to reach peace of mind on a troubling subject. [Maybe Jameson is a model of this kind of persuasive writing?]

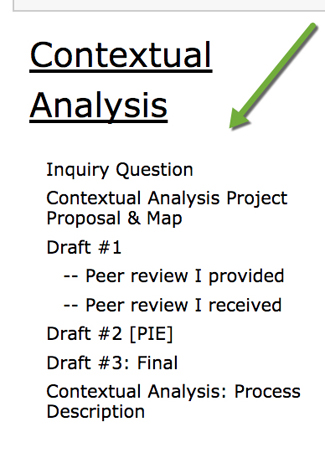

A couple of people have written asking for samples of good informational abstracts. I think in our case, it’ll be important for you to include your method (contextual analysis), your framework (ideological, historical, cultural, social, etc.), and a summary of your findings, conclusion, or the implications of your research (“Every wolf in Yellowstone therefore is more than just a wolf. Imbued with profound symbolic meaning, each wolf embodies the divergent goals of competing social movements involved in the reintroduction debate”).

Here are some good resources:

From our Writing Center:

The Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (p. 26) suggests that good abstracts are written in a way that is accurate, non-evaluative, coherent and readable, and concise.

Usually a conventional, thesis-driven essay — the conventional academic model has an identifiable thesis, intro, body, conclusion, like the example in your St. Martin’s Handbook; our Op-Ed model is more flexible

More often than not, out-and-out defeat of another — as in a debate, for example — is not only unrealistic but also undesirable. Rather, the goal is to persuade readers to see an issue in a particular way, or to help them understand, or move them toward some action, or to cause them to be newly interested in your issue.

This is where we get to see the writer struggling with an issue and engaging in truth-seeking behavior

Often, a writer must enter into conversation with others and collaborate in seeking the best possible understanding of a problem, exploring all possible approaches and choosing the best alternatives. As all good critical thinkers know, there’s always more than just one side of the story, there’s always more than two sides of the story: there’s always a third side of the story. Some people phrase that as “there’s your truth, there’s my truth, and then there’s the real truth.”

We can think of this one as the “Leslie Jameson model”

Sometimes you will find yourself arguing primarily with yourself, and those arguments often take the form of intense meditations on a theme, or even of prayer. In such cases, you may be hoping to transform something in yourself or to reach peace of mind on a troubling subject.

From your St. Martin’s Handbook — 2.9a “Arguing for a purpose” (p. 186)

Intro

There are these two young fish swimming along and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says “Morning, boys. How’s the water?” And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes “What the hell is water?”

Conclusion (22 minutes later)

It is about the real value of a real education, which has almost nothing to do with knowledge, and everything to do with simple awareness; awareness of what is so real and essential, so hidden in plain sight all around us, all the time, that we have to keep reminding ourselves over and over:

“This is water.”

“This is water.”

It is unimaginably hard to do this, to stay conscious and alive in the adult world day in and day out.

Transcript (PDF)

Audio (YouTube)

[Many researchers argue that …] As neighborhoods get white-washed and become trendy tourist locations, important historical information and cultural narratives become extinct.

[Some urban planners assert that …] Cities are notorious cultural melting pots. As cities become more and more the same and lose their sense of individuality to cater the visions and desires of the white middle class, the world as a whole loses its sense of individuality.

And did you see this OED definition of gentrify?: “”To renovate or convert (housing, esp. in an inner-city area) so that it conforms to middle-class taste; to render (an area) middle-class.”

[Cultural critics have asked …] Are you really experiencing the uniqueness of a city if you can get the same brunch, shop at the same trendy boutique, and work out at the exact same yoga studio in Chicago, New York and Los Angeles?

[Some people argue that …] universities seek to attract the most academic, experienced, and worldly students from around the world, putting less and less emphasis on curriculum and credential teachers.

[Others claim that …] Today it’s all about construction the best resume and finding a job.

[Some research suggests that …] Higher expectations and a push for timely graduation have made students less concerned about the value of the education they are receiving, and more worried if their transcript will look good.

“The Top Twenty: A Quick Guide to Troubleshooting Your Writing” in your St. Martin’s Handbook and here.

Looking for examples in the NYT:

Looking for examples in the NYT:

Commas in a non-restrictive clause (St. Martin’s 44c):

performing schools succeed.” (Friedman, 10/30)

performing schools succeed.” (Friedman, 10/30)Commas after introductory elements (44a):

From a Chronicle of Higher Education article, “Heard on My Recent Book Tour: Frustration and Doubt About Higher Education”

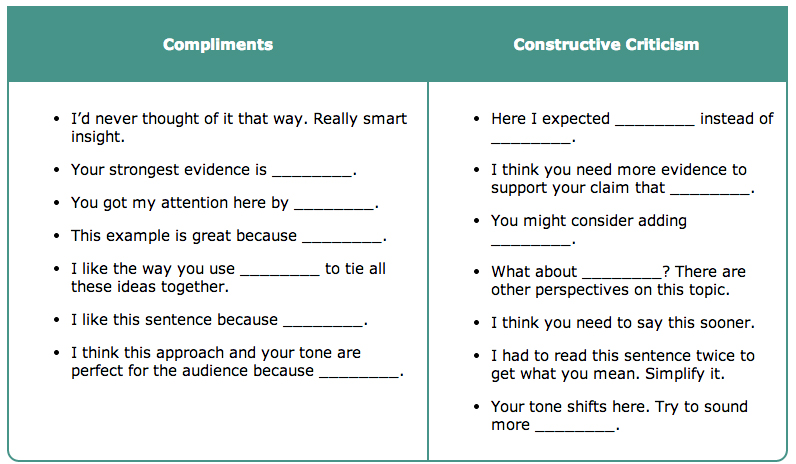

The most helpful reviewers are interested in the topic and the writer’s approach to it. They ask questions, make concrete suggestions, report on what is confusing and why, and offer encouragement. Good reviewers give writers a new way to see their drafts so that they can edit effectively. After reading an effective review, writers should feel confident about taking the next step in the writing process.

Peer review is difficult for two reasons. First, offering writers a way to imagine their next draft is just hard work. Unfortunately, there’s no formula for giving good writing advice. But you can always do your best to offer your partner a careful, thoughtful response to the draft and a reasonable sketch of what the next version might contain. Second, peer review is challenging because your job as a peer reviewer is not to grade the draft or respond to it as an English instructor would. As a peer reviewer, you will have a chance to think alongside writers whose writing you may consider much better or far worse than your own.

Being a peer reviewer should improve your own writing as you see how other writers approach the same assignment. So make it a point to tell writers what you learned from their drafts; as you express what you learned, you’ll be more likely to remember their strategies. Also, you will likely begin reading your own texts in a new way. Although all writers have blind spots when reading their own work, you will gain a better sense of where readers expect cues and elaboration.

St. Martin’s 4b.: Reviewing peer writers — at least two fully developed paragraphs

Focus on:

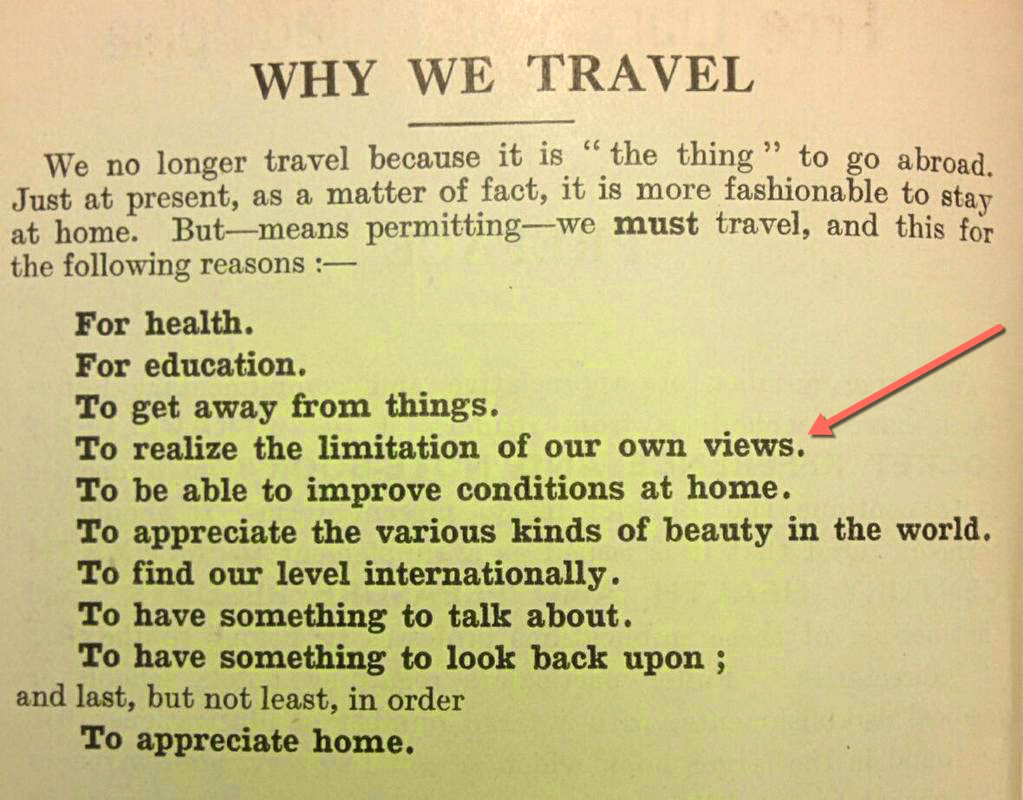

St. Augustine believed that “because God has made us for Himself, our hearts are restless until they rest in Him.” We often think of restlessness as a malady. Thus, we urgently need to reclaim the etymology of restlessness — “stirring constantly, desirous of action” — to signal our curiosity toward what isn’t us, to explore outside the confines of our own environment. Getting lost isn’t a curse. Not knowing where we are, what to eat, how to speak the language can certainly make us anxious and uneasy. But anxiety is part of any person’s quest to find the parameters of life’s possibilities. — From “Reclaiming Travel”

Police officers “know that in a swearing match between a drug defendant and a police officer, the judge always rules in favor of the officer.” At worst, the case will be dismissed, but the officer is free to continue business as usual. Second, criminal defendants are typically poor and uneducated, often belong to a racial minority, and often have a criminal record. “Police know that no one cares about these people,” Mr. Keane explained.

— From “Why Police Lie Under Oath”

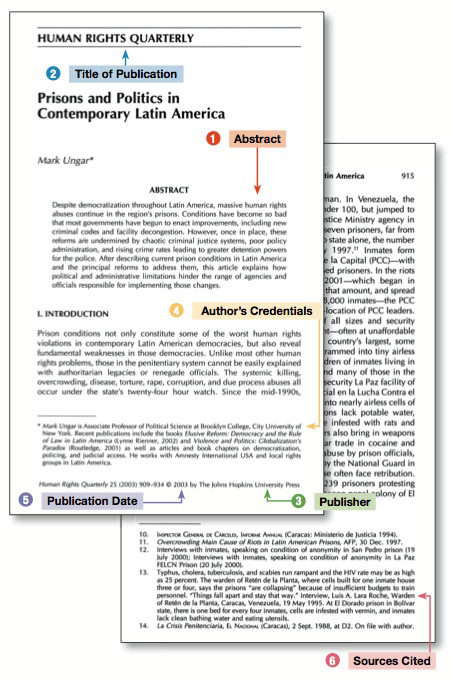

St. Martin’s Guide: “Integrating Sources into Your Writing” (3.13)

A good seating arrangement can prevent problems; however, “withitness,” as defined by Woolfolk, works even better: Withitness is the ability to communicate to students that you are aware of what is happening in the classroom, that you “don’t miss anything.” With-it teachers seem to have “eyes in the back of their heads.” They avoid becoming too absorbed with a few students, since this allows the rest of the class to wander. (359)

In contrast to parentheses, dashes give more rather than less emphasis to the material they enclose. Many word-processing programs will automatically convert two typed hyphens into a solid dash (—).

“The world is a book, and those who do not travel read only a page.”

“Men go abroad to wonder at the heights of mountains, at the huge waves of the sea, at the long courses of the rivers, at the vast compass of the ocean, at the circular motions of the stars, and they pass by themselves without wondering.”

— St. Augustine

Benning, Jim. “Interview with Henry Rollins: Punk Rock World Traveler.” World Hum. 11 Nov. 2011. Web. 22 Apr. 2015.

The Traveller’s Companion: A Travel Anthology. The Century Co., 1932.

As a result, many feel lost or overwhelmed. They feel a hunger to live meaningfully, but they don’t know the right questions to ask, the right vocabulary to use, the right place to look or even if there are ultimate answers at all.

As I travel on a book tour, I find there is an amazing hunger to shift the conversation. People are ready to talk a little less about how to do things and to talk a little more about why ultimately they are doing them.

This is true among the young as much as the older. In fact, young people, raised in today’s hypercompetitive environment, are, if anything, hungrier to find ideals that will give meaning to their activities. It’s true of people in all social classes. Everyone is born with moral imagination — a need to feel that life is in service to some good.

Brooks: What Is Your Purpose?

Brooks: First Steps

The size and shape of fonts affects reading and comprehension to a much greater extent than most of us give them credit for — thus making them deeply rhetorical choices. We’ll talk about some of those differences in class and look at examples, including default fonts in your favorite word-processing program and in Digication. (more…)

The size and shape of fonts affects reading and comprehension to a much greater extent than most of us give them credit for — thus making them deeply rhetorical choices. We’ll talk about some of those differences in class and look at examples, including default fonts in your favorite word-processing program and in Digication. (more…)

[P] Every wolf in Yellowstone therefore is more than just a wolf. Imbued with profound symbolic meaning, each wolf embodies the divergent goals of competing social movements involved in the reintroduction debate. Framed by environmentalists and their wise use opponents as another line in the sand in their ongoing battle for the heart and soul of the West, wolf reintroduction is a high-stakes political conflict. [I] Wolf recovery is often portrayed by environmentalists as being symptomatic of a culture in transition–an inevitable change (Askins, 1995). It is an image that plays especially well with the media: “[T]he wolf issue pits the New West against the Old West” (Johnson, 1994, p. 12), a milestone in the “transformation of power” from the Old West (Brandon, 1995, p.8). [E] Wolf restoration clearly represents change, but sound bites that reduce the social struggle over wolves to an “inevitable” transition from the old to the new are inadequate. They do not explain the underlying social issues driving the transformation. They do not capture the essence of social negotiation, the give-and-take of political exchange between social movements struggling to define the western landscape. Nor do they acknowledge that these social issues will remain after the wolf controversy has exited the center stage of public policy discourse.

Wilson, Matthew. “The Wolf in Yellowstone: Science, Symbol, or Politics? Deconstructing the Conflict between Environmentalism and Wise Use.” Society & Natural Resources. 10(1997): 453-468. (more…)

And keep up the good work.

The informal guardrails of life were gone, and all was arbitrary harshness.

That’s happened across many social spheres — in schools, families and among neighbors. Individuals are left without the norms that middle-class people take for granted. It is phenomenally hard for young people in such circumstances to guide themselves.

Yes, jobs are necessary, but if you live in a neighborhood, as Gray did, where half the high school students don’t bother to show up for school on a given day, then the problems go deeper.

The world is waiting for a thinker who can describe poverty through the lens of social psychology. Until the invisible bonds of relationships are repaired, life for too many will be nasty, brutish, solitary and short.

“One of the most salient features of our culture is that there is so much bullshit. Everyone knows this. Each of us contributes his [or her] share. But we tend to take the situation for granted. Most people are rather confident of their ability to recognize bullshit and to avoid being taken in by it. So the phenomenon has not aroused much deliberate concern, or attracted much sustained inquiry.

“One of the most salient features of our culture is that there is so much bullshit. Everyone knows this. Each of us contributes his [or her] share. But we tend to take the situation for granted. Most people are rather confident of their ability to recognize bullshit and to avoid being taken in by it. So the phenomenon has not aroused much deliberate concern, or attracted much sustained inquiry.

In consequence, we have no clear understanding of what bullshit is, why there is so much of it, or what functions it serves.” (p1)

” … she is not concerned with the truth-value of what she says. That is why she cannot be regarded as lying; for she does not presume that she knows the truth, and therefore she cannot be deliberately promulgating a proposition that she presumes to be false: Her statement is grounded neither in a belief that it is true nor, as a lie must be, in a belief that it is not true. It is just this lack of connection to a concern with truth — this indifference to how things really are — that I regard as of the essence of bullshit.” (p10) (more…)

Preface

1.

IT DOESN’T COME with any instructions, because it’s meant to be the most normal, easy, obvious and unremarkable activity in the world, like breathing or blinking.

(more…)

“I tell college students that by the time they sit down at the keyboard to write their essays, they should be at least 80 percent done. That’s because “writing” is mostly gathering and structuring ideas.” – David Brooks

In another New York Times Op-Ed, “Engaged or Detached?” Brooks claims that writers need to maintain a detached perspective in order to honestly inform their readers. Brooks defines the differences between a detached writer and an engaged writer as the difference between truth seeking and activism. The goals of an engaged writer are to have a limited “immediate political influence” while detached writers have more realistic goals, aiming to provide a more objective view.

“Boredom” in English derives from the noun “bore” — but interestingly, even the OED doesn’t know the etymology:

Paragraph #2

Wolves in Yellowstone provide a potent metaphor for both opponents and proponents of federal land use management. Beasts of deeply held cultural myth, wolves are the ultimate symbol of wilderness and untamed nature. As such, wolves embody deep social passions that swirl around the issue of federal land use policy in the American West. On the one hand, environmental activists argue that the wolf is the last remaining link in a chain ecological restoration to a prehistoric time, a chance to restore the largest predator in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem to the its former glory when the shite man first came west. On the other hand, wise use activists argue that wolf reintroduction is primarily a strategy to gain increased social control over private property.

Paragraph #3

Every wolf in Yellowstone therefore is more than just a wolf. Imbued with profound symbolic meaning, each wolf embodies the divergent goals of competing social movements involved in the reintroduction debate. Framed by environmentalists and their wise use opponents as another line in the sand in their ongoing battle for the heart and soul of the West, wolf reintroduction is a high-stakes political conflict. Wolf recovery is often portrayed by environmentalists as being symptomatic of a culture in transition–an inevitable change (Askins, 1995). It is an image that plays especially well with the media: “[T]he wolf issue pits the New West against the Old West” (Johnson, 1994, p. 12), a milestone in the “transformation of power” from the Old West (Brandon, 1995, p.8). Wolf restoration clearly represents change, but sound bites that reduce the social struggle over wolves to an “inevitable” transition from the old to the new are inadequate. They do not explain the underlying social issues driving the transformation. They do not capture the essence of social negotiation, the give-and-take of political exchange between social movements struggling to define the western landscape. Nor do they acknowledge that these social issues will remain after the wolf controversy has exited the center stage of public policy discourse.

Wilson, Matthew. “The Wolf in Yellowstone: Science, Symbol, or Politics? Deconstructing the Conflict between Environmentalism and Wise Use.” Society & Natural Resources. 10(1997): 453-468.

Critical thinking is, in short, self-directed, self-disciplined, self-monitored, and self-corrective thinking. It presupposes assent to rigorous standards of excellence and mindful command of their use. It entails effective communication and problem solving abilities and a commitment to overcome our native egocentrism and sociocentrism. – Adapted from Richard Paul and Linda Elder, The Miniature Guide to Critical Thinking Concepts and Tools, Foundation for Critical Thinking Press, 2008

“A persistent effort to examine any belief or supposed form of knowledge in the light of the evidence that supports it and the further conclusions to which it tends.” Edward M. Glaser.An Experiment in the Development of Critical Thinking. 1941.

From “Middle Class, but Feeling Economically Insecure”

I am always on the lookout for instances when New York Times writers reference or gesture toward work done in academic disciplines — and your majors — especially when it’s deployed as having explanatory power, which is the case here:

“Middle income is not necessarily the same thing as middle class,” said Rakesh Kochhar, a senior research associate at Pew. Even as the proportion of households in the middle-income brackets has narrowed, people’s identification with the middle class remains broad.”

“That’s because the middle-class label is as much about aspirations among Americans as it is about economics. But a perspective that was once characterized by comfort and optimism has increasingly been overlaid with stress and anxiety.”

“Part of the reason has to do with lost jobs and stagnating incomes. At the same time, the psychological frame — how Americans feel about their security and prospects — and the sociological — how they stack up in relation to their parents, friends, neighbors and colleagues — are just as important as purely economic criteria. And on both these counts, middle-class Americans say they are feeling increasingly vulnerable.”

Louise Rosenblatt explains that readers approach texts in ways that can be viewed as aesthetic or efferent. The question is why the reader is reading and what the reader aims to get out of the reading:

A New York Times example might be reading Market News.

A New York Times example might be Jameson’s Mark My Words. Maybe.

But now, in the 21st century:

Habits of mind refers to ways of approaching learning that are both intellectual and practical and that will support your success in a variety of fields and disciplines. The framework identifies eight habits of mind essential for success in college writing

|

“We are what we find, not what we search for.” – Piero Scaruffi

Spring Quarter, 2015

In WRD 104 we focus on the kinds of academic and public writing that use materials drawn from research to shape defensible arguments and plausible conclusions. As the second part of the two-course sequence in First Year Writing, WRD 104 continues to explore relationships between writers, readers, and texts in a variety of technological formats and across disciplines:

You’ll be happy to note, I hope, that we build on your previous knowledge and experiences; that is, we don’t assume that you show up here a blank slate. We assume that you have encountered interesting people, have engaging ideas, and have something to say. A good writing course should prepare you to take those productive ideas into other courses and out into the world, where they belong, and where you can defend them and advocate for them.

If you have a project from another course that you would like to continue, or a community project that would benefit from rigorous research, or a professional aspiration that needs research-based support, this is the course for you.

Writing Center

It’s no secret around here that students who take early and regular advantage of DePaul’s Center for Writing-based Learning not only do better in their classes, but also benefit from the interactions with the tutors and staff in the Center.