- Genre: Contextual Analysis

- Audience: educated, curious readers

- Length: 1500-1750 words

- Sources: minimum of eight credible sources, at least four of which come from peer-reviewed scholarly publications, and one book

- Background: St. Martin’s e-Handbook: choosing topics (12); conducting research (13); integrating sources (15)

It is likely that in WRD103 you were asked to work on a textual analysis or a rhetorical analysis that looked closely at an isolated text and you interpreted it with descriptive language from that text. This is a good intellectual exercise that will always result in a particular kind of meaning, based solely on that isolated text.

A contextual analysis is a different intellectual exercise altogether: by putting an issue into context, you will create a new kind of meaning; for our purposes, a phenomenon or an issue can only be properly understood within the context it occurred. Your contextual analysis will tell us what that meaning is.

- A contextual analysis depends on a contextual framework to view your issue from a broader perspective in order to see things you wouldn’t notice if you analyze only textual or rhetorical features. The frameworks might derive from historical, theoretical, biographical, cultural, social, ideological or political-economic information. Research and analysis based on an identifiable contextual framework helps academic writers establish credibility because they are writing with a method, with perspective, and with analytic authority.

- A contextual analysis puts sources into conversation with each other, where we can compare and contrast writers’ values and rhetorical strategies.

- A contextual analysis has powerful explanatory features and capabilities because you are analyzing writers’ positions, rhetorical strategies, attitudes toward readers, and values; the sum of those inquiries should tell us something about the nature of the issue you choose to explore. Context and a point of view bring meaning to knowledge; your contextual analysis will tell us what that meaning is.

By this point in the term, and after an individual conference with me, you should have identified an issue from reading the New York Times that interests you for further inquiry. An “issue” is different than a “topic” because with an issue we can identify places where reasonable people can have different perspectives and take different rhetorical positions; an issue is debatable, and a topic is not.

Your challenges for this project are to [1] first spend some time in inquiry mode, asking questions — to whom does this issue matter? Why? What is interesting about it? What is important about it? What is at stake? — [2] to research and analyze your issue via some contextual framework and, [3] to compose your contextual analysis based on your research.

Possible examples:

- What is happiness?

- Is there such a thing as a suburban ethos?

- Are leaders born that way, or are they made?

- Where does confidence come from? Be sure to click on Brooks’s first link, to “The Confidence Code”: “In studies, men overestimate their abilities and performance, and women underestimate both. Their performances do not differ in quality.”

- What is the “middle class”?

- What is feminism?

- What is empathy?

- Why do people compose & share “selfies”?

- What is the relationship between art and fashion?

- What would a reception study of the film Hunger Games tell us about where the film resides in the public imagination?

- What is the history of Pilsen and how is it usually reflected in histories of Chicago?

- What is privacy?

- What is the purpose of college?

- Is there a “rhetoric of terrorism?”

- What is a “Millennial”?

These examples are meant to show the possible scope of a contextual analysis project; I will negotiate yours with you, and will encourage you to invest this time on an issue that you genuinely care about, and for which you want to make compelling, successful arguments. Also note that these representative examples are based on inquiry — not on a thesis or based on argument — and that is where we will start: with questions.

Our Process:

- Brainstorming Inquiry Questions: Week 3

- Preliminary Inquiry Question: Week 4

- Project Proposal & Map: Week 4

- Online Library workshop: Week 4

- Library Workshop: Week 5

- Project First Draft: Week 5

- Project Second Draft (workshop & peer review): Week 6

- Project Third Draft: Proofreading Draft: Week 7

- Project Final Draft & Self Assessment: Week 7

- Op-Ed Essay: Week 8

Examples of contextual-analysis essays

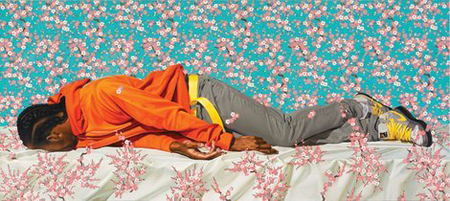

* Who’s Afraid of Post-Blackness? What It Means to Be Black Now — note how the writer weaves sources and examples throughout: quoting, delivering statistics, wrestling with contradictions, integrating a range of voices, all in the service of a single line of inquiry.

* “Do Birds Have Emotions?”

“Emotions, feelings, awareness, sentience, and consciousness are all difficult concepts. They are tricky to define in ourselves, so is it any wonder they are difficult in birds and other nonhuman animals? Consciousness is one of the big remaining questions in science, making it both an exciting and a highly contentious area of research.”

You can see the writer’s contextual-analysis map: “Biologists, psychologists, and philosophers have argued over these issues for years, so I cannot hope to resolve them. Instead, I have adopted Darwin’s approach—thinking about what might be going on in a bird’s head and imagining a continuum, with displeasure and pain at one end and pleasure and rewards at the other.”