“One purpose of a liberal arts education is to make your head a more interesting place to live inside of for the rest of your life.” —Mary Patterson McPherson, President, Bryn Mawr College

“I thought that the future was a place—like Paris or the Arctic Circle. The supposition proved to be mistaken. The future turns out to be something that you make instead of find. It isn’t waiting for your arrival, either with an arrest warrant or a band; it doesn’t care how you come dressed or demand to see a ticket of admission. It’s no further away than the next sentence, the next best guess, the next sketch for the painting of a life’s portrait that may or may not become a masterpiece. The future is an empty canvas or a blank sheet of paper, and if you have the courage of your own thought and your own observation, you can make of it what you will.” —Lewis Lapham

“It ain’t where ya from, it’s where ya at!” —KRS-ONE, Ruminations

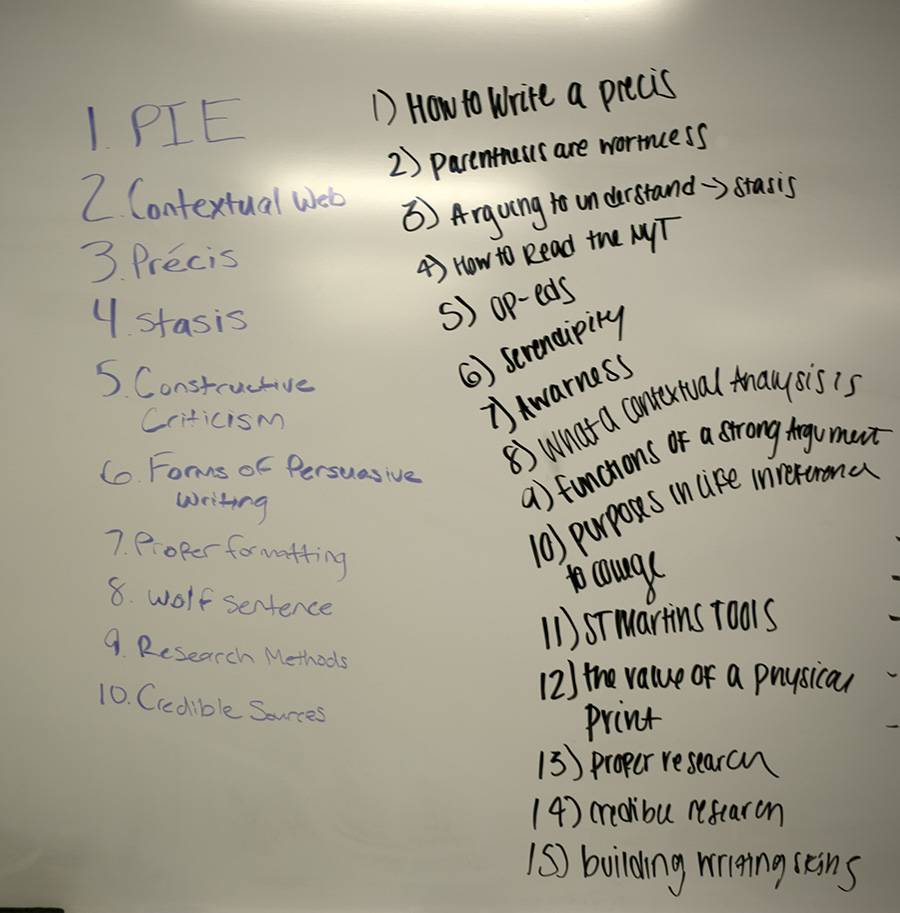

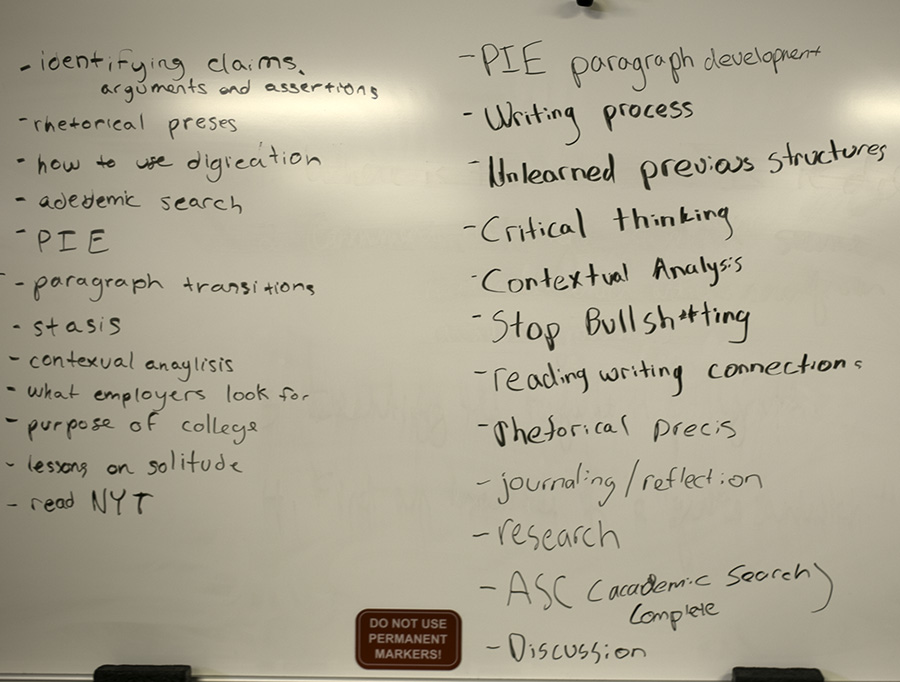

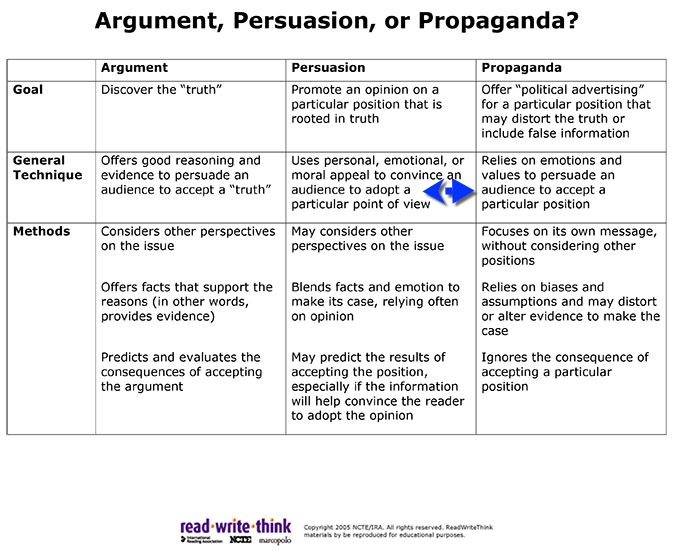

Unclear writing, now as always, stems from unclear thinking–both of which ultimately have political and economic implications. A well cultivated critical thinker:

Unclear writing, now as always, stems from unclear thinking–both of which ultimately have political and economic implications. A well cultivated critical thinker: