New York Times, remixed.

Photo by Sam.

Thanks, Jimena!

Thanks, Sam!

ask a new question and you will learn new things

We’ve read Jenna Wortham a few times this term — My Selfie, Myself and last week’s Page A1 article on Snapchat — and today she has an interesting article on Facebook (I was initially drawn to the accompanying illustration):

“One purpose of a liberal arts education is to make your head a more interesting place to live inside of for the rest of your life.” —Mary Patterson McPherson, President, Bryn Mawr College

“I thought that the future was a place—like Paris or the Arctic Circle. The supposition proved to be mistaken. The future turns out to be something that you make instead of find. It isn’t waiting for your arrival, either with an arrest warrant or a band; it doesn’t care how you come dressed or demand to see a ticket of admission. It’s no further away than the next sentence, the next best guess, the next sketch for the painting of a life’s portrait that may or may not become a masterpiece. The future is an empty canvas or a blank sheet of paper, and if you have the courage of your own thought and your own observation, you can make of it what you will.” —Lewis Lapham

“It ain’t where ya from, it’s where ya at!” —KRS-ONE, Ruminations

“Your love is a delicate flower” — (from the Jon Lovett video that we watched)

I already raised this in the 1:00 section, and we’ll get to it in the 2:40 section today: typeface choices.

The size and shape of fonts affects reading and comprehension to a much greater extent than most of us give them credit for — thus making them deeply rhetorical choices. We’ll talk about some of those differences in class and look at examples, including default fonts in your favorite word-processing program and in Digication.

You can use Pixlr.com to create custom banners:

After you have your SoundCloud URL ready:

> Create a new module: Image/Video/Audio

> Select “Replace this Media”

> Select “Media from the Web (new)”

> Paste in Sound Cloud URL

> Publish

This will be helpful as we plan Technology & Literacy Projects, especially for those of you planning to explore the print/digital reading context:

Louise Rosenblatt [110] explains that readers approach the text — the New York times, let’s say — in ways that can be viewed as aesthetic or efferent. The question is why the reader is reading and what she aims to get out of the reading. Is the text established primarily to help readers gain information with as little reading possible, or is it established in order to create an aesthetic experience?

Thus, according to Rosenblatt, reading — and meaning-making? — happens only in the reader’s mind; it does not take place on the page, on the screen, or in the text, but in the act of reading.

![]()

The November issue of Scientific American includes this article: “Why the Brain Prefers Paper.” (If you are logging in from campus, you should be able to access the PDF online by logging in; if not, let me know.)

The entire article is interesting and timely for us. Here are the concluding paragraphs:

Some digital innovators are not confining themselves to imitations of paper books. Instead they are evolving screen-based reading into something else entirely. Scrolling may not be the ideal way to navigate a text as long and dense as Herman Melville’s Moby Dick, but the New York Times, the Washington Post, ESPN and other media outlets have created beautiful, highly visual articles that could not appear in print because they blend text with movies and embedded sound clips and depend entirely on scrolling to create a cinematic experience. Robin Sloan has pioneered the tap essay, which relies on physical interaction to set the pace and tone, unveiling new words, sentences and images only when someone taps a phone or a tablet’s touch screen. And some writers are pairing up with computer programmers to produce ever more sophisticated interactive fiction and nonfiction in which one’s choices determine what one reads, hears and sees next.

When it comes to intensively reading long pieces of unembellished text, paper and ink may still have the advantage. But plain text is not the only way to read.

DePaul’s Definition of literacy

“We are helping students become more literate. By literacy, we do not mean merely learning to read and write academic discourse, but also learning ways of reading, writing, thinking, speaking, listening, persuading, informing, acting, and knowing within the contexts of university discourse(s) and the multiple discourses in the world beyond the university.”

This definition might be worth reflecting on at some length before, during, and after your Technology & Literacy Projects.

9a Arguing for a purpose — page 186

To win

The most traditional purpose of academic argument, arguing to win, is used in campus debating societies, in political debates, in trials, and often in business. The writer or speaker aims to present a position that prevails over or defeats the positions of others.

To convince and persuade

More often than not, out-and-out defeat of another is not only unrealistic but also undesirable. Rather, the goal is to convince other persons that they should change their minds about an issue.

To reach a decision or explore an issue

Often, a writer must enter into conversation with others and collaborate in seeking the best possible understanding of a problem, exploring all possible approaches and choosing the best alternative.

To change yourself

Sometimes you will find yourself arguing primarily with yourself, and those arguments often take the form of intense meditations on a theme, or even of prayer. In such cases, you may be hoping to transform something in yourself or to reach peace of mind on a troubling subject.

Looking for examples in the NYT

Commas in a non-restrictive clause (St. Martin’s 44c):

Commas after introductory elements (44a):

“Well, sometimes I use my inexperience or lack of knowledge as the drama of the essay. The essay becomes a kind of biography of an idea — how it reveals itself and comes to a fullness. The essay can begin with inexperience, and as it teaches the reader, so also it teaches the writer. There’s something very exciting about that kind of progress.”

— From an interview with Richard Rodriquez.

The quote made me think about some of your exploratory essays, where some of you are starting from scratch, and where the reader is learning along with you.

Rodriquez was one of my favorite writers in college:

— Hunger of Memory: The Education of Richard Rodriguez

— Days of Obligation: An Argument with My Mexican Father

— Brown: The Last Discovery of America

— Darling: A Spiritual Autobiography

From a profile of Heidi Nelson Cruz in the New York Times:

By the time she arrived at Claremont McKenna College, friends and professors knew her as a whip-smart economics and international relations double-major who would graduate Phi Beta Kappa and a driven and ambitious young woman who was already planning a professional career.

In Mr. Cruz, friends and colleagues say, she finally met not just her match, but also her intellectual equal.

“Heidi is a synthesizer, whereas Ted tends to blow ahead on one line of reasoning,” said Lawrence B. Lindsey, the chief economic adviser on Mr. Bush’s 2000 campaign. Mrs. Cruz pulled together “different points of view,” he said, and Mr. Cruz is “more of a hard-charger on one point of view.”

From the OED:

Sense 6. a. In wider philosophical use and generally: The putting together of parts or elements so as to make up a complex whole; the combination of immaterial or abstract things, or of elements into an ideal or abstract whole. (Opposed to analysis.) Also, the state of being put so together.

From your St. Martin’s Guide:

When you read and interpret a source—for example, when you consider its purpose and relevance, its author’s credentials,its accuracy, and the kind of argument it is making—you are analyzing the source. Analysis requires you to take apart something complex (such as an article in a scholarly journal) and look closely at the parts to understand the whole better.

For academic writing you also need to synthesize—group similar pieces of information together and look for patterns—so you can put your sources (and your own knowledge and experience) together in an original argument. Synthesis is the flip side of analysis: you already understand the parts, so your job is to assemble them into a new whole. [see 3.12e — Synthesizing sources — for examples.]

The newspaper is itself an outlandish creation: a smudgy, portable, disposable offline data platform made of tree pulp, mass-produced every day on huge printers and trucked for a fee to your home, or sold from the sidewalk. Newspapers are not the societal bulwark they once were; their authority is challenged and ubiquity is slipping. But artists who use and love newspapers do so for good reason.

They are fountains of words, meaning, preliminary history. They are ready-made targets for irony, allusion and commentary, ripe for riffing and manipulation. They are beautiful in themselves, bursting with aesthetic riches — photographic and commercial art, comics, op-ed illustrations. They are also abundant, cheap and rectangular. And you can dip them in strips into flour and water and make beautiful things.

Their place in art, as art, is honored and unshakable, which is reason enough to curse the glowing screens that are relentlessly shoving them aside.

And for those of you writing on “What is the Purpose of College?”

— Brooks again: “The Practical University”

— Tugend: “Vocation or Exploration? Pondering the Purpose of College”

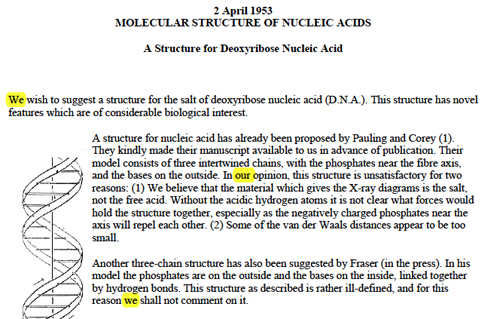

It seems to me that if it was good enough for Watson & Crick — they discovered the molecular structure of DNA, the Double Helix — it’s good enough for you:

Watson, J. D., & Crick, F. H. C. (1953) A structure for deoxyribose nucleic acid (DNA). Nature 171, 737–738.

Watson, J. D., & Crick, F. H. C. (1953) A structure for deoxyribose nucleic acid (DNA). Nature 171, 737–738.

“What we don’t learn from the diary is what happened after the last entry, on Aug. 1, 1944.”

Playing Cat and Mouse With Searing History

Something to consider as we think about our Op-Ed essays this week:

“A speaker persuades an audience by the use of stylistic identifications; the act of persuasion may be for the purpose of causing the audience to identify itself with the speaker’s interests; and the speaker draws on identification of interests to establish rapport between herself or himself and the audience.” — Kenneth Burke, A Rhetoric of Motives.

Identification, Burke reminds us, occurs when people share some principle in common — that is, when they establish common ground. Persuasion should not begin with absolute confrontation and separation but with the establishment of common ground, from which differences can be worked out. Imagining common ground is the point of our work in stasis.

“Almost all good writing begins with terrible first efforts. You need to start somewhere. Start by getting something — anything — down on paper. A friend of mine says that the first draft is the down draft — you just get it down. The second draft is the up draft — you fix it up. You try to say what you have to say more accurately. And the third draft is the dental draft, where you check every tooth, to see if it’s loose or cramped or decayed, or even, God help us, healthy.” — Anne Lamott, “Shitty First Drafts”