Article: “Hidden After Offending, Mural at a State Office Is Back, for Peeks Only”

My experience reading this article in four different ways:

- First, in print, early a.m., with coffee [physical environment: Starbucks]

- Next, via the Replica edition PDF [physical environment: home, on a laptop or in my office, on a desktop]

- Next, on my phone [everywhere — CTA Red Line, on the street, sitting outside]

- Finally, via the web NYTimes.com version [in my office, throughout the day]

I start my day with the print version of the New York Times. This particular article caught my attention because it is about an interesting piece of art, has political implications, and raises issues about representation and race.

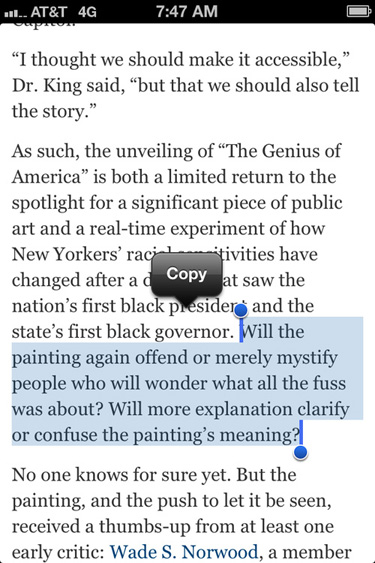

I enjoyed reading it in print. I did pull out my phone and searched the mural’s title and history at one point, however, and made a note to search later in the library database, just out of curiosity. I annotated a few phrases that stood out — “Will the painting again offend or merely mystify people who will wonder what all the fuss was about? Will more explanation clarify or confuse the painting’s meaning?” — and thought about what great questions those are. These are the kinds of prompting, generative questions that I like to ask about almost anything I read in the New York Times, and with some minor adjustments, we could ask the same things about Op-Eds and editorials, as well.

In the print edition, the mural’s image is in black and white. In the Replica Edition, however, it is in color, quite beautifully, I thought:

And on my phone, the color appears in high resolution:

Because I knew that we would be talking about these print-and-digital issues in class, I tried to be self-consciously aware of my reading experience — was I scrolling and skimming or was I trying to do a close, careful reading? Was I comprehending what I was reading on the screen as much as I was in print? It is difficult to measure those activities in the moment, of course, but the heightened awareness of my process did allow me to think more deeply about the article; it’s not hard to do that when you are reading the same text four times in one day.

One unintended outcome and consequence is that I felt I understood the issues and questions surrounding the mural and it allowed me some genuine curiosity about a piece of art that I might have otherwise passively inventoried in my regular, daily reading practice. For example, one of the ambiguities in the painting revolves around the black-male figure in the lower-right:

“Amid that symbolic swirl, in the lower right corner, is a striking and some say unsettling image: a slave in loincloth being held under the arms by a well-dressed white man.”

According to the article, “It was that image and its potential symbolism — was the slave being lifted or restrained? — that led state education officials to hide “Genius” behind heavy emerald-color drapery in 2000, after department staff members, some of them African-American, complained that the mural was offensive.”

I was able to increase the size of the image on my phone by spreading it with my finger and thumb, focusing on that part of the painting. The placement of the white man’s hands does suggest lifting, which could affect one’s analysis and reading of the mural.

This is another reason I want to read more about the mural’s history, context, criticism, and analysis, so that I can see how other people have made their analyses for “lifted or restrained.”

Finally, the annotation problem. Writing on the paper itself is and was easy; it’s how most of us were trained to read in academic environments: skim for important concepts, ideas, key terms, people, dates, and questions to return to later. I am a regular annotator in books, magazines, and in the New York Times.

But annotating in any of the digital versions of the New York Times is impossible. I did the best I could with the highlight/copy feature on my phone, but it is not practical to read and to annotate like that all day every day. Highlighting passages on such a small screen invites decontextualizing — I cannot see what comes before and after — and where would I keep them?

I opened the web version of the article and used Scrible to annotate passages and quotes that struck me as important. This is an interesting process. I can see what comes before and after (text recall); I can color-code passages; I can share a link to my annotations. The potential downsides? It is another proprietary system to sign up for, it might not always remain free, and I do not know the extent to which students might be willing to invest the time needed to annotate in this fashion. It’s not as easy as jotting notes in the margin.

This is a literacy issue, not a technical problem. People do not read and write in the same ways. It seems unlikely that people annotate in the same ways and that their motivations for annotating are the same. Nobody is going to give me a quiz on “Hidden After Offending, Mural at a State Office Is Back, for Peeks Only,” so I am free to annotate based on curiosity, questions, ways to remember, and to prompt my own future rereading should I decide to return to this article in the future.

Notes

In my sample reading description, I’ve bolded some key terms and phrases from our discussions:

Comprehension

Comprehension Database

Database Curiosity

Curiosity Resolution

Resolution Skimming

Skimming Analysis

Analysis Annotate

Annotate Text Recall

Text Recall Literacy

Literacy

- [Did not mention efferent/aesthetic]

- [Did not mention metacognitive learning regulation]

- [Did not mention serendipity]