As if a text …

October 8, 2013NYT: Great Betrayals

Insidiously, the new information disrupts their sense of their own past, undermining the veracity of their personal history. Like a computer file corrupted by a virus, their life narrative has been invaded. Memories are now suspect …

Accompanying illustration by Anthony Russo.

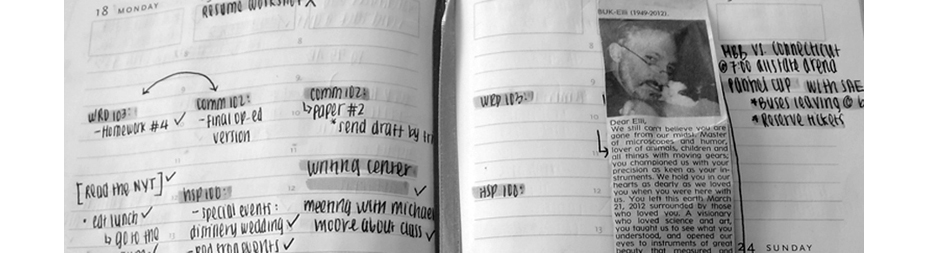

Peer Review Ideas: notes from Thursday

- It turns out that not everyone has read the assignment. Do you get the sense that the writer whose work you are reviewing has read the assignment and knows what a Rhetorical Analysis is? What a Rhetorical Analysis is supposed to do?

- Combination of MSWord mark-up tools and a few paragraphs in letter form on global issues based on St. Martin’s 1.4b (page 75) — see especially “Responding to early-stage drafts” and “Reviews of Emily Lesk’s draft”

- Does the writer discuss tone?

- Does the writer discuss emotional, logical, and credible forms of rhetorical appeals? (pathos, logos, ethos)? Also see in your St. Martin’s Guide, 2.8d.: “Reading emotional, ethical, and logical appeals”

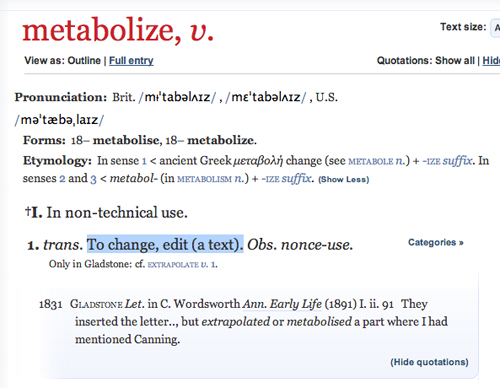

- OED?

- Coherent?

- Inspires curiosity?

- Does the writer do a good job with word-level analysis? For example, recall the “Two-State Illusion” writer’s use of third-person pronouns they, them, which can be distancing and “othering,” rhetorically speaking, whereas Kristof often depends on we, us, first-person pronouns that establish a different kind of relationship with readers: we, us.

- Arrangement/organization: does it make sense? What should come first? What should come next? What should come after that?

- Should the writer visit the Writing Center?

Advice for reviewers: please take the time to review St. Martin’s 1.4b (pages 75-87). You’ll see excellent and relevant examples of peer reviews there.

Is It Going Away to College if College Is Close to Home?

From “When College Is Close to Home, What are the Boundaries?”

According to The Chronicle of Higher Education, colleges not far from home are increasingly becoming the first choice of many students. Twenty percent of the respondents of this year’s freshman survey of full-time, four-year degree students said that being close to home was a very important factor in their college choice, continuing a slight upward trend that began four decades ago. (The figure was 16 percent in 1983.)

Followup with reader comments: “Is It Going Away to College if College Is Close to Home?”

Interesting Rhetorical Précis possibility …

September 25, 2013“His seven-second explanation of the expansive new health care law …”

September 24, 2013How should we read page A1?

We have several different methods available to us: sometimes we can read it as a representation of reality; we can read it as a particular editorial ideology; we can read it as a “table of contents of the world”; we can read it as a practical news source; we can read it critically — what doesn’t get reported on A1?

For 10 weeks, we have A1 to read together. If we’re smart — and we are — we will visit all of those reading methods. There is another method that I would like to look at with you this week, and it’s related to developing a contextual and historical sensibility. In a recent article in another publication (The New Yorker magazine) on online learning, a historian is quoted as saying,

” … the historian’s mind-set is the person who sees what’s going on, today, and assumes that whatever’s happening is not happening for the first time. And that whatever we’re seeing must have happened in some iteration, at some point, sometime in the past somewhere. And that those versions of the kinds of change that we see around us in various scales are just the latest installment of a very long series of similar such changes.”

“That history is sort of repeating in some ways. But isn’t history also cumulative—that when we see it happening a second time it’s somehow different from the first time?”

Page One

Some things to do before watching Page One:

- Get a feel for the kinds of issues that David Carr writes about

- See in particular his article, “At Sam Zell’s Tribune, Tales of a Bankrupt Culture”

- Get a feel for the kinds of issues that Brian Stelter writes about

- See Stelter’s Twitter feed

- Review the issues behind the Pentagon Papers

- Review the issues behind Wikileaks

“Wise men [and women] in every tradition tell us that suffering brings clarity, illumination; for the Buddha, suffering is the first rule of life, and insofar as some of it arises from our own wrongheadedness — our cherishing of self — we have the cure for it within. Thus in certain cases, suffering may be an effect, as well as a cause, of taking ourselves too seriously. I once met a Zen-trained painter in Japan, in his 90s, who told me that suffering is a privilege, it moves us toward thinking about essential things and shakes us out of shortsighted complacency; when he was a boy, he said, it was believed you should pay for suffering, it proves such a hidden blessing.”

NYT/Pico Iyer, “The Value of Suffering” 8 September 2013.

Literacy events and literacy practices

Literacy events and literacy practices are key to understanding literacy as a social phenomenon.

Literacy events and literacy practices are key to understanding literacy as a social phenomenon.

Literacy events serve as concrete evidence of literacy practices. Heath (1982) developed the notion of literacy events as a tool for examining the forms and functions of oral and written language. She describes a literacy event as “any occasion in which a piece of writing is integral to the nature of participants’ interactions and their interpretive processes” (p. 93). Any activity in which literacy has a role is a literacy event. As Barton and Hamilton (2000) describe, “Events are observable episodes which arise from practices and are shaped by them. The notion of events stresses the situated nature of literacy, that it always exists in a social context” (p. 8).

Barton and Hamilton (2000) describe literacy practices as “the general cultural ways of utilizing written language which people draw upon in their lives. In the simplest sense literacy practices are what people do with literacy” (p. 8). Literacy practices involve values, attitudes, feelings, and social relationships. They have to do with how people in a particular culture construct literacy, how they talk about literacy and make sense of it. These processes are at the same time individual and social. They are abstract values and rules about literacy that are shaped by and help shape the ways that people within cultures use literacy. Street (1993) described literacy practices, which are inclusive of literacy events, as “‘folk models’ of those events and the ideological preconceptions that underpin them” (pp. 12-13).

Art & newspapers

Our first issue of the New York Times this week coincides with Fashion Week in New York and the Impressionism, Fashion, and Modernity exhibit at the Chicago Art Institute. The Art Institute offers free General Admission to Illinois residents every Thursday from 5:00 to 8:00pm.

The image to the right, Édouard Manet’s “Woman Reading” is included in the exhibit. She seems to be reading a newspaper, which a note in the Impressionism, Fashion, and Modernity exhibit points out, were instrumental in deciding tastes and style in 19th-century Paris. Another note: “But it is not clear that she is reading; she might be using the large pages to screen surreptitious looks coming from her right. In any event, there seems to be a hint of avidity in her expression.”

More newspaper art.

Welcome to WRD 103: Rhetoric & Composition

Great minds discuss ideas.

Average minds discuss events.

Small minds discuss people.

— Eleanor Roosevelt

Life’s prerequisites are courtesy and kindness, the times tables, fractions, percentages, ratios, reading, writing, some history — the rest is gravy, really.

— Nicholson Baker, “Wrong Answer: The Case Against Algebra II”

WRD 103 introduces you to the forms, methods, expectations, and conventions of college-level academic writing. We also explore and discuss how writing and rhetoric create a contingent relationship between writers, readers, and subjects, and how this relationship affects the drafting, revising, and editing of our written — and increasingly digital and multimodal — projects.

In WRD 103, we will:

- Gain experience reading and writing in multiple genres in multiple modes

- Practice writing in different rhetorical circumstances, marshaling sufficient, plausible support for your arguments and advocacy positions

- Practice shaping the language of written and multimodal discourses to your audiences and purposes, fostering clarity and emphasis by providing explicit and appropriate cues to the main purpose of your texts

- Practice reading and evaluating the writing of others in order to identify the rhetorical strategies at work in written and in multimodal texts.

You’ll be happy to note, I hope, that we build on your previous knowledge and experiences; that is, we don’t assume that you show up here a blank slate. We assume that you have encountered interesting people, have engaging ideas, and have something to say. A good writing course should prepare you to take those productive ideas into other courses and out into the world, where they belong, and where you can defend them and advocate for them.

Finally, it’s no secret around here that students who take early and regular advantage of DePaul’s Center for Writing-based Learning not only do better in their classes, but also benefit from the interactions with the tutors and staff in the Center.

A well cultivated critical thinker:

- Raises vital questions and problems, formulating them clearly and precisely;

- Gathers and assesses relevant information, using abstract ideas to interpret it, effectively comes to well-reasoned conclusions and solutions, testing them against relevant criteria and standards;

- Thinks openmindedly within alternative systems of thought, recognizing and assessing, as need be, their assumptions, ideologies, implications, and practical consequences; and

- Communicates effectively with others in figuring out solutions to complex problems.

Critical thinking is, in short, self-directed, self-disciplined, self-monitored, and self-corrective thinking. It presupposes assent to rigorous standards of excellence and mindful command of their use. It entails effective communication and problem solving abilities and a commitment to overcome our native egocentrism and sociocentrism. – Adapted from Richard Paul and Linda Elder, The Miniature Guide to Critical Thinking Concepts and Tools, Foundation for Critical Thinking Press, 2008

“A persistent effort to examine any belief or supposed form of knowledge in the light of the evidence that supports it and the further conclusions to which it tends.” Edward M. Glaser. An Experiment in the Development of Critical Thinking. 1941.