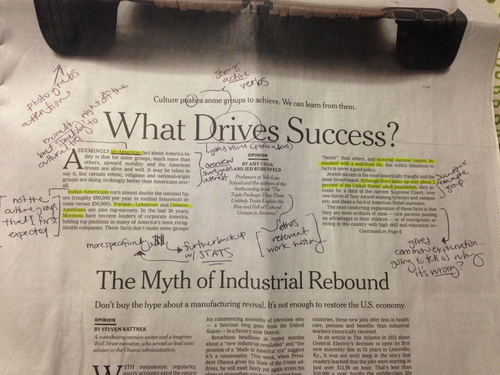

Rhetorical Analysis: “What Drives Success?”

In The New York Times article, “What Drives Success?” by Amy Chua and Jed Rubenfield, these two professors and authors claim that success of certain cultural groups is not an occurrence due to genetic magic or even long-term cultural tradition but rather, an outcome of three combined character traits grounded into individuals: a superiority complex, insecurity, and impulse control. Although seen primarily in certain cultural groups today, they highlight that various other groups have accessed this formula at different times throughout history. They describe the common rising and falling of cultural groups in human society and argue this is a result of losing one or more of the three characteristics that drove them toward success in the first place. Chua and Rubenfield utilize each of the three primary appeals, ethos, pathos, and logos, to effectively build and strengthen their claim throughout the entire article.

The use of ethos, an ethical appeal, begins even before the first sentence of the article. Along with their names in the author section, Chua and Rubenfeld highlight their positions as professors at the prestigious Yale Law School and as authors of a new book entitled “The Triple Package: How Three Unlikely Traits Explain the Rise and Fall of Cultural Groups in America. This creates an expectation of reliability almost immediately; they purposefully namedrop their institution of employment and their book on the very subject of the article in order to form a trustworthy bond with readers. Further, Chua and Rubenfeld include with their argument numerous studies and statistics from credible sources. Regardless of the content within these studies, the status of their sources as well known and well respected again encourages readers to believe the information presented. Interestingly, and almost amusingly, the authors commonly preface impending evidence with the term, “Research shows…” in cases where exact sources are not stated. They build upon an ethical appeal in these ways in order to reinforce their perceptive claims of societal success and increase audience support.

The article draws connections with pathos, an emotional appeal, as a mode for influencing perception of the information presented. They include widespread examples across cultural groups and fields such as education, occupation, and even mental wellbeing to provide a human face for the topic being discussed. The authors use attention grabbing evidence including one that claims, “Asian-American students reported the lowest self-esteem of any racial group, even as they racked up the highest grade,” to evoke an emotional reaction from the reader and deepen their processing of the argument. In the study mentioned above, Chua and Rubenfeld brilliantly support their claim that success, in the sense of economic stability and high occupational standing, is correlated with insecurity by arousing a negative reaction in the reader.

The study’s findings may surface uneasiness in the audience regarding the students’ insecurity which then increases their attentiveness as they process the evidence, which clearly shows insecurity paired with high academic performance. The main point made: the reader doesn’t need to like the argument but this does not mean they should avoid recognizing it as a true. Adding to the unconventionality of the emotional appeals used, Chua and Rubenfeld sprinkle negatively charged concepts like “Un-American” and “taboo” directed against their stance, which, on the surface, would seem to weaken their argument. But in fact, the authors include this as a jab at their counterargument. The opposition commonly uses these as part of the fallacious reasoning tactic ad populum, with the focus on extreme positive or negative concepts such as patriotism or terrorism rather than the real issue at hand. Chua and Rubenfeld reinforce their claims and fight against possible opposing points through the use of highly original emotional appeals.

Most prevalent among the appeals used are countless logical appeals, or ones that relate to logos. Evidence found in studies or statistical observations accompany nearly every mention of cultural groups including Asian, African, Iranian, and Cuban-Americans as well as Mormons, Jews, and various religious groups. Worth mentioning is the fact that Chua and Rubenfeld do not allow the studies make their argument for them. Instead, they incorporate the statistical evidence naturally into the flow of their writing and make concise commentary on the studies used that helps incorporate the presented support into the context of their argument. This allows for fluid understanding of the concepts presented while providing the evidence necessary to draw a complete logical picture. We can see this tactic used clearly in various parts of the article including the mention that, “In 1960, second-generation Greek-Americans reportedly had the second highest income… [but] the fortunes of WASP elites have been declining for decades.” Alone, this census report would be enough to build the authors’ argument regarding the rise and fall of culture groups’ successes, but Chua and Rubenfeld went further. They add to the more direct evidence source by explaining that, “Group success in America often tends to dissipate after two generations.” They continue to build their argument by rationalizing the roots of two-generation occurrence, leading to their thesis regarding the combined characteristics at work in groups on the rise. The article utilizes logos through the consistent inclusion of strong, relevant studies combined with the explained critical thought processes of the authors.

Chua and Rubenfield’s use of ethos, pathos, and logos provide a sturdy foundation for their claims about the success factors of rising culture groups. They build upon information in a manner that peaks interest and relates with our contemporary culture, claiming that now is as relevant an “opportunity” as ever for Americans to tap into the three character traits of a superiority complex, insecurity, and impulse control. Perhaps through this new understanding we can further success beyond the individual level and onto betterment as a collective.

Chua, Amy and Jed Rubenfeld. “What Drives Success?” The New York Times 26 Jan. 2014: SR BW 1+. Print.

I Write, Therefore I Am:

A Rhetorical Analysis of David Brooks’s “Engaged or Detached?”

In the New York Times article, “Engaged or Detached?” David Brooks claims that writers need to maintain a detached perspective in order to honestly inform their readers. Brooks defines the differences between a detached writer and an engaged writer as the difference between truth seeking and activism. The goals of an engaged writer are to have a limited “immediate political influence” while detached writers have more realistic goals, aiming to provide a more objective view.

In order to support his claims Brooks uses a variety of rhetorical strategies. For example, he measures the detached writing method against the engaged writing method. Brooks lays out the detached writer’s motivations as the desire to teach or seek out the truth. He then goes on to describe the specific motivations of the engaged writer: energizing the political base, and mobilizing – rather than persuading — the audience that already allies with his ideology.

Brooks’s articles also depends on rhetorical strategies of pathos and logos. The diction triggers emotions while he predominantly employs his logic and reasons to convince his audience. For example, “at his worst, the engaged writer slips into rabid extremism and simple minded brutalism. At her worst, the detached writer slips into a sanguine, pox-on-all-your-houses complacency and an unearned sense of superiority.” His use of “brutalism, extremism, and superiority” evokes an emotional response due to their negative connotation.

Brooks’s own ethos is revealed by writing this article as a detached writer. He encourages writers to stray away from an engaged perspective in order to maintain mental hygiene which is being honest with oneself. “Detached writers generally understand that they are not going to succeed in telling people what to think.” His argument is one for the case of curiosity and humility.

Brooks suggests the style you write can “end up dictating our morals” therefore you are what you write.

What can all of this mean to a class of college writers? All great things start with an idea. As college writers, we have to realize that before we can take any action, we need to be confident in ourselves and figure out what it is we want to accomplish. We become attached to the world by being detached. We are the future idea generators of this rock spinning through space. We need to find the truth ourselves before we go imposing what we think are truths onto others.