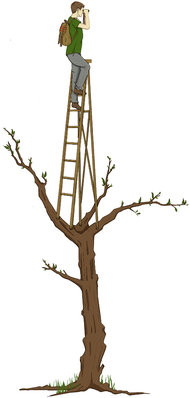

“We are what we find, not what we search for.”

– Piero Scaruffi

Welcome to WRD104 — Spring Quarter, 2014

In WRD 104 we focus on the kinds of academic and public writing that use materials drawn from research to shape defensible arguments and plausible conclusions. As the second part of the two-course sequence in First Year Writing, WRD 104 continues to explore relationships between writers, readers, and texts in a variety of technological formats.

You’ll be happy to note, I hope, that we build on your previous knowledge and experiences; that is, we don’t assume that you show up here a blank slate. We assume that you have encountered interesting people, have engaging ideas, and have something to say. A good writing course should prepare you to take those productive ideas into other courses and out into the world, where they belong, and where you can defend them and advocate for them.

If you have a project from another course that you would like to continue, or a community project that would benefit from rigorous research, or a professional aspiration that needs research-based support, this is the course for you.

Writing Center

Finally, it’s no secret around here that students who take early and regular advantage of DePaul’s Center for Writing-based Learning not only do better in their classes, but also benefit from the interactions with the tutors and staff in the Center.

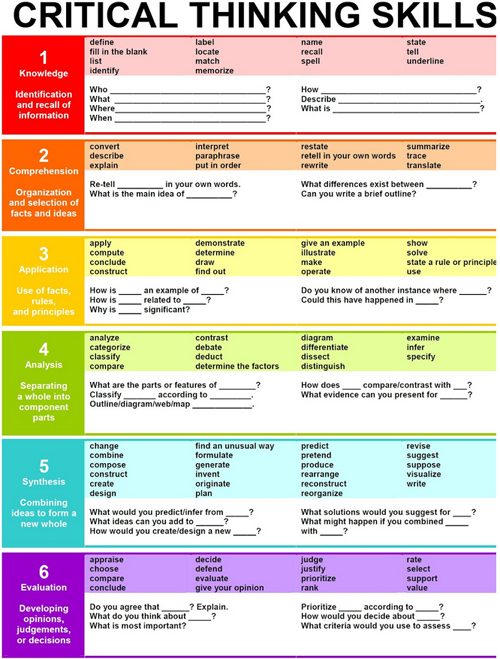

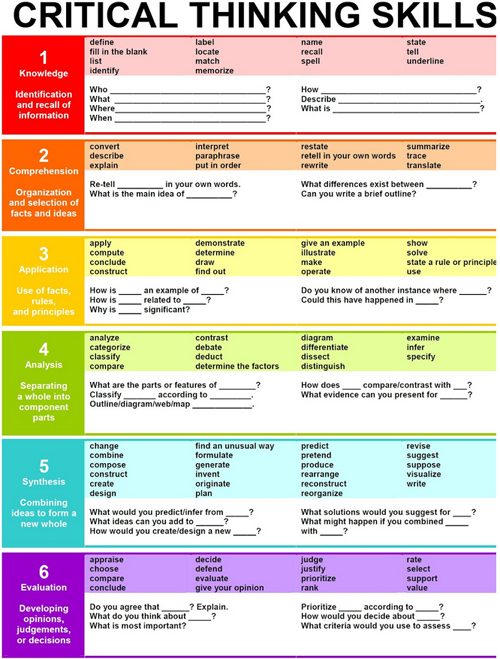

A Well Cultivated Critical Thinker:

- Raises vital questions and problems, formulating them clearly and precisely;

- Gathers and assesses relevant information, using abstract ideas to interpret it, effectively comes to well-reasoned conclusions and solutions, testing them against relevant criteria and standards;

- Thinks openmindedly within alternative systems of thought, recognizing and assessing, as need be, their assumptions, ideologies, implications, and practical consequences; and

- Communicates effectively with others in figuring out solutions to complex problems.

Critical thinking is, in short, self-directed, self-disciplined, self-monitored, and self-corrective thinking. It presupposes assent to rigorous standards of excellence and mindful command of their use. It entails effective communication and problem solving abilities and a commitment to overcome our native egocentrism and sociocentrism. – Adapted from Richard Paul and Linda Elder, The Miniature Guide to Critical Thinking Concepts and Tools, Foundation for Critical Thinking Press, 2008

“A persistent effort to examine any belief or supposed form of knowledge in the light of the evidence that supports it and the further conclusions to which it tends.” Edward M. Glaser.An Experiment in the Development of Critical Thinking. 1941.

From

From