Course Introduction, Background & Goals

“What should be our society’s relationship with nature? What are the intellectual causes of the current environmental crisis? These ‘great questions’ of environmental studies are essentially humanistic inquiries into ethics and values.”—Jeanne Kay, “Human Dominion over Nature in the Hebrew Bible,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers.

In this course we explore the intellectual, social, scientific, and rhetorical backgrounds of sustainability. We read technical and imaginative literature, view and discuss visual arts, and try to come to a collective understanding of the movement that has attracted so much academic, community, and environmental attention and commitment. Our approaches will be to explore the assumptions, values, and practices of sustainability wherever we find them, with an eye toward practical, meaningful applications in our personal and professional lives, and in our community.

Sustainability has a now-classic definition: “Sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs,” originally articulated by the U.N.’s Our Common Future: Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development (1987). In that context, it’s interesting to think about how Adam and Eve may have felt upon their expulsion from their rich orchard to labor on the land and to grow their own food:

Cursed is the ground because of you

in toil you shall eat of it all the days of your life;

thorns and thistles it shall bring forth to you;

and you shall eat the plants of the field.

In the sweat of your face you shall eat bread.

(Genesis 3: 17-19)

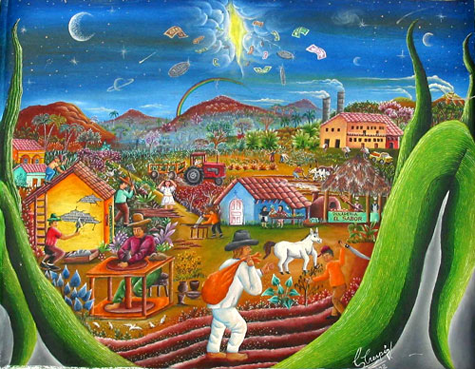

Since 1987 sustainability has taken on many additional meanings—spiritual, global, economic, scientific, social, cultural, and more. If the average person is overwhelmed by conflicting messages found in the media regarding climate change and sustainability, and my Mom sure is, what role can engineers, scientists, writers, editors, and artists play in developing a coherent and active understanding of the concept? I propose that we frame some of these questions in terms of creativity and the imagination.

We’ll look at and discuss some visual art in this class, read parts of the bible, poems, farm manuals, personal narratives, and interdisciplinary research in ethnobiology, hydrology, and microbial ecologies. We’ll meet people from campus and from the local community whose work in sustainability take on many different approaches.

Why “Rhetoric & Poetics of Sustainability”?

To begin, we will frame our work in a couple of humanities concepts that will help us organize our work, and find ways to make that work meaningfully generative:

Poetics refers to an organizing principle—a systematic study—of literature, information, and knowledge. A poetic principle is not necessarily always an artistic or creative principle, but the word does come from the Greek philosopher Aristotle’s text by the same name, in which he analyzes the “characteristic functions” of poetic genres.

Rhetoric is the language that people and communities use to negotiate meaning and values. The languages may be visual, textual, auditory; they may be persuasive, which connects rhetoric to one of its classical roots; rhetoric is also a generative tool for discovery, and a means for analyzing forms of communication. All representations of the environment and of climate change—engineering, scientific, literary, artistic, educational, legislative—are rhetorical.

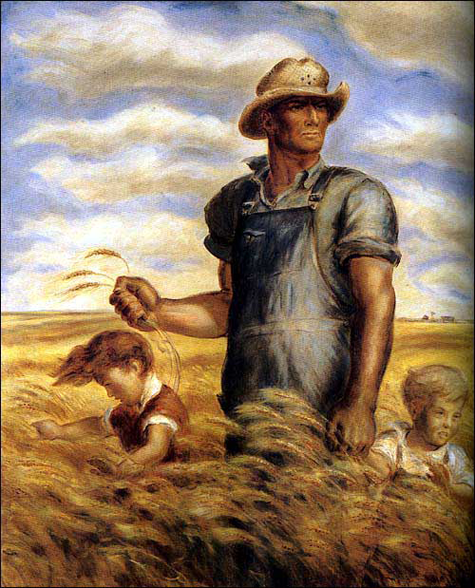

J.S. Curry, Our Good Earth, 1942 (see his Wisconsin Landscape, 1939)

Santiago Crespin Sin Titulo (Dollars From Heaven)

John Gast’s “American Progress” (1872)

We’ll also inquire into various technical, scientific, and argumentative pieces that appeal to our attention in different ways. For example, what is the appeal and the organizing principle here?

We are involved now in a profound failure of imagination. Most of us cannot imagine the wheat beyond the bread, or the farmer beyond the wheat, or the farm beyond the farmer, or the history beyond the farm. Most people cannot imagine the forest and the forest economy that produced their houses and furniture and paper; or the landscapes, the streams, and the weather that fill their pitchers and bathtubs and swimming pools with water. Most people appear to assume that when they have paid their money for these things they have entirely met their obligations.

—Wendell Berry, In Distrust of Movements