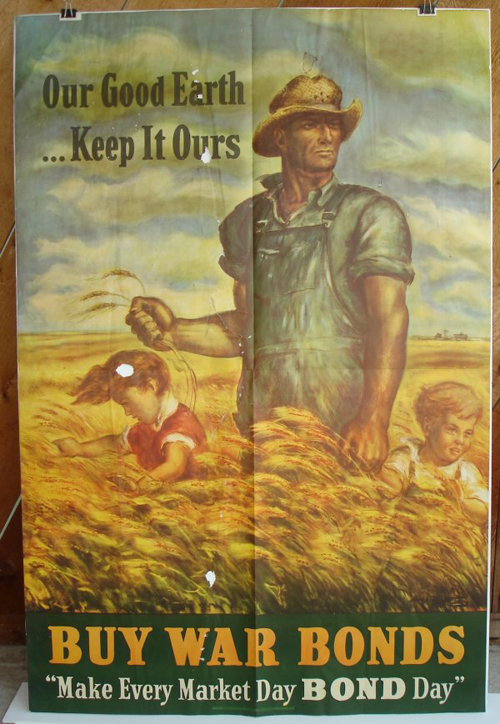

This page contains images of — and some context for — the 1942 print of J.S. Curry’s “Our Good Earth,” that has been restored and is currently hanging in my office, SAC 362 at DePaul University.

There are additional resources via the links to the right.

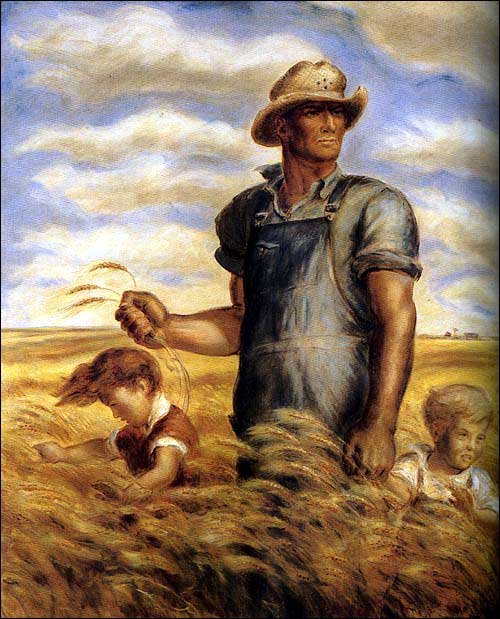

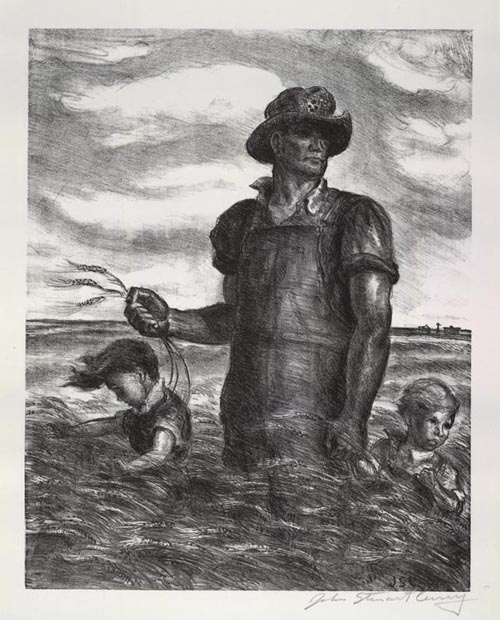

Curry’s original painting, based on his 1938 lithograph, hangs in the Chazen Art Museum in Madison, and it has an interesting history as a recreated war bonds poster in 1942. According to the Library of Congress,

John Steuart Curry, along with other American Regionalist artists, presented visions of America that found beauty and dignity in the lives of ordinary citizens. This concern was shared by Farm Security Administration photographers, who set out document the Depression, and in the process created indelible images which often blurred the lines between art, and information. Here, Curry’s hero stands watch over playing children, and ‘amber’ waves of grain suggesting plenty, hope, and patriotic identity. (The War Bond print was produced by Government Printing Office 1942, # O-472519.)

Our Good Earth, Chazen Museum, Madison, 61 x 50 inches.

Our Good Earth, Chazen Museum, lithograph, 12 7/8 x 10 1/4 inches

This is how the print looked when I bought it, and before it was restored in California and framed in Houghton, Michigan:

In 1999, the Hemphill Fine Arts Gallery had an exhibition named Our Good Earth: The Landscape at the End of the Century: “the title for the show is drawn from a work by the great American regionalist painter John Steuart Curry. Painted in 1940, Curry’s Our Good Earth, a masterpiece of its time, expresses a nearly religious belief in American heartland values. In support of the United States effort in WWII, Curry’s painting was reproduced as a poster and re-titled Our Good Earth, Keep It Ours. Some sixty years later each word in Curry’s original title carries equally charged, but changed meaning.”

Another description is from the book John Steuart Curry: Inventing the Middle West:

Once America entered the war, Curry attempted to rally to the cause, reworking an 1938 lithograph into a painting entitled Our Good Earth, for a U.S. Department of Treasury propaganda poster. In it, a muscular young farmer stands in a wheat field, two children playing at his side. This stalwart figure symbolizes the power of American agriculture, geared up to feed millions of GIs fighting to defend the earth for future generations, as represented by the innocent children. The farmer’s noble form recalls idealized images of Renaissance humanism and, by implication, the optimistic understanding of human nature implicit in Renaissance art. Specifically, the figure recalls Adam in Albrecht Dürer’s engraving Adam and Eve (1504):

Although Curry reverses the pose and places the right arm holding agricultural produce, and his massive upper body all stem from Dürer … Despondent at the outbreak of World War II, yet called upon to use his talents for the war effort, he resorted to familiar imagery to make his point. Our Good Earth portrays a virile farmer, the American Adam, holding out the promise of an abundant harvest. Yet this same farmer is also representative of fallen humanity, raising this crop to feed GIs who will, after all, fight and kill in the war. The inherent irony in the image was made emphatic when the Department of Treasury reproduced his lithograph with the caption, Our Good Earth—Keep it Ours” to underscore the war time struggle. (145-46)

Various other sources and correspondences suggest degrees of Curry’s ambivalence toward having his work used in support of the war effort.

The next section willinclude some German propaganda from the same time period:

Farm Family from Kahlenberg, 1939 by Adolf Wissel