I have collected a few example everyday texts and annotations here in order to help you imagine the collection and organization of your own projects.

While planning this course for the Autumn Quarter in 2014, I noticed this photo on the front page of the New York Times, when they were covering immigration-reform issues and anti-immigrant protests last year on a pretty regular, almost-daily, basis:

It was an unusal photograph, I thought, but could not quite put my finger on why right away. I saved a copy and looked at it a couple of times. Then, when teaching the class in September, I pulled it up again and shared it with the class — much like I am doing with you, now — as an example of an everyday text. Because I had the image up on an overhead projector, I was able to see some details that I had not noticed the first couple of times:

It occured to me, standing there in front of the class, which is often the worst time to have an insight, that their flip flops bothered me. Who wears flip flops to a protest? I then began to make other assumptions about the two protestors: that they are middle-class white people; that they are dressed more for running errands at Home Deport and eating at Applebee’s than engaging in the kinds of protest environments that I am used to seeing:

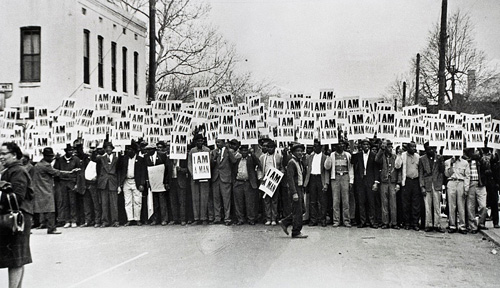

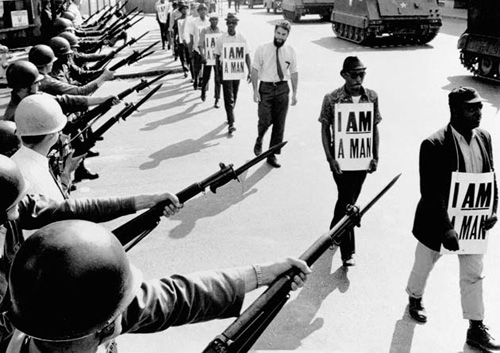

Memphis Sanitation Workers Strike, Memphis, 1968, where Martin Luther King Jr. was assisinated

“It wasn’t just that sanitation workers in Memphis were being improperly paid or overworked or that they didn’t have the respect of the community. In Memphis, TN, that year, black sanitation workers were not allowed to seek refuge from the rain inside the cab of the garbage trucks they worked on, only in the back of the truck where the garbage went — the compressor unit where you throw the garbage in and a steel panel comes down to shove the garbage inside the truck and compresses it. That’s where black workers could come in from the rain when it rained. You couldn’t get in the cab of the truck if you were black. Two of those men, Echol Cole and Robert Walker, on a rainy day in Memphis, had been crushed to death in a mechanical malfunction. That’s why King went to Memphis.” (Examiner.com)

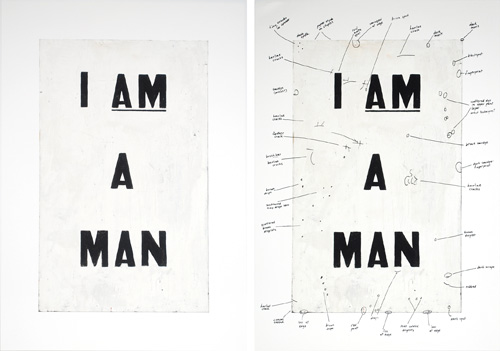

“Ligon is best known for intertextual works that re-present American history and literature, in particular narratives of slavery and civil rights, for contemporary audiences. His work engages a powerful mix of racial and gender-oriented struggles for the self, leading viewers to reconsider problems inherent in representation.

“Ligon is best known for intertextual works that re-present American history and literature, in particular narratives of slavery and civil rights, for contemporary audiences. His work engages a powerful mix of racial and gender-oriented struggles for the self, leading viewers to reconsider problems inherent in representation.

Untitled (I Am a Man) is just such a representation—a signifier—of the actual signs carried by 1,300 striking African American sanitation workers in Memphis, made famous in Ernest Withers’ 1968 photographs. Prompted by the wrongful deaths of two coworkers from faulty equipment, the strikers marched to protest low wages and unsafe working conditions. They took up the slogan “I Am a Man” as a variant on the first line of Ralph Ellison’s prologue to Invisible Man, “I am an invisible man.” By deleting the word “invisible,” the Memphis strikers asserted their presence, making themselves visible in standing up for their rights. Martin Luther King Jr. traveled to Memphis to address the striking workers; the next day, he was assassinated.

This painting is Ligon’s most important and iconic work. As the first object in which he used a selected text, Untitled (I Am a Man) is his breakthrough. He took pains to differentiate the painting from the original signs, avoiding a one-to-one relationship by reorganizing the line breaks. And while he preserved the original black-on-white of the sign, his choice to paint the black letters in eye-catching enamel calls attention to a black figure (“Man”) as a text that replaces the human form in figurative painting. Throughout his career, Ligon has used “blackness” as a trope for both personal and collective experience. As Ligon has said (paraphrasing Muhammed Ali), “It’s not about me. It’s about we.” The deliberately rough surface of the painting, which Ligon later documented by having a condition report made as an ancillary work of art, seems to index the scars and struggles of the work’s great subject.” (National Gallery)

Chicago Teachers Union Strike, 2012 — notice how the Memphis sign from 1968 — I AM A MAN — is now I AM A TEACHER:

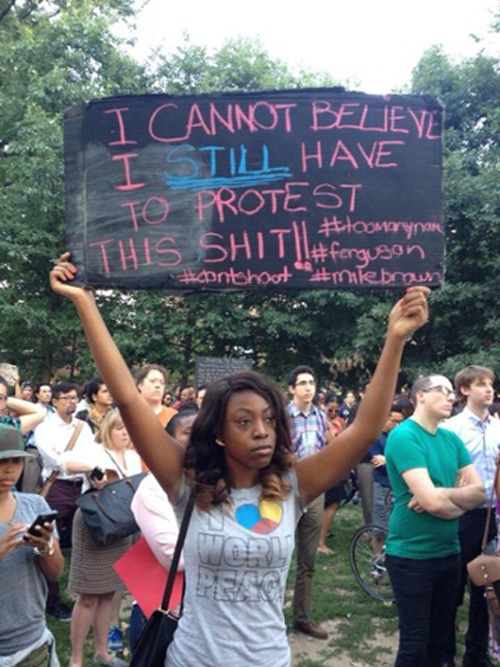

Ferguson, Missouri

But back to the New York Times:

After some extended reflection about why I was having the kinds of reaction I was toward these protestors and their protest sign, I was able to inventory other observations, with the help of the class:

- Their protest sign contains no pronouns, unlike many of the other examples, above, which makes me question their commitment to this particular cause. Where’s their pronoun?

- It’s almost easy to overlook a major visual component: this is a photograph of protestors having their photo taken by a third person (on a smartphone?)

- Is there such a thing as “illegal children”?

- Is he wearing cargo shorts?

What I learned in this process that my own ideology, assumptions, and biases color how I read the image. Then I went back to see how it was presented, in context, on Page A1 of the New York Times (July 4th, 2014). I notice how it is contrasted with a top-of-the-page image — patriotic, with Uncle Sam — such that the two protestors, in contrast, now seem practically un-American in their uncompassionate, mocking protest discourse.

But it was how they are positioned to look that way, at least in part, that leads me — along with my own assumptions and biases to view them in that manner. After my extended reflections, look how easy it is for me to apply our everyday text framework:

- Exhibit complexity in terms of the linguistic resources we draw upon to make and understand them

The lack of a pronoun in their protest sign seems like a simple observation, but as I consider its absesne, it does make for a more complex understanding of the rhetoric of protest signs - Perform critical rhetorical functions for the participants involved

I admire people who take the time to engage in public, civic, protest, even when I disagree with them. As anti-immigration protestors, their sign does function in rhetorically powerful way, and it got them on the front page of the New York Times. The image also had critical rhetorical functions on me, the viewer. - Powerfully summon and propagate the social orders in which we live

Immigration - Everyday texts are constitutive of something or someone; as agents of communication, they surround us constantly, and it is surely to our benefit to be able to understand what they’re saying