Michael Moore

Op-Ed Essay Draft #2

Why I am a Feminist and Why You Should Not Listen to Me

The easiest way to put it is this: I am using the second half of my life to make up for and to apologize for the first half of my life.

I wasn’t a terrible person — I didn’t do terrible things — but like most young men, I was pretty clueless about most things. I was raised in a culture — born in the 1950’s and raised in the 1960’s and 1970’s — when women were sexualized visually everywhere: cigarette ads; car ads; television shows; beer ads. Men weren’t sexualized. We were expected to be quietly masculine, to drive (preferably) a red Camaro, to have a job, to provide for a family. Women, it seemed, were only required to wear bikinis everywhere and to kind of glisten. What I know now is that there are culture industries dedicated to creating and sustaining those images: magazines; films; advertising. It still goes on today. Your generation seems a little more self-aware about it, but the messages are still there, every day all day. Everywhere you look.

I wasn’t a terrible person — I didn’t do terrible things — but I did not always treat women with respect. I was one of those guys who didn’t call back. In today’s terms, I would be the guy who didn’t text, while knowing that you were waiting for that text. That, it seems to me now, is more an issue of respect — and maybe of dignity? — than anything else.

I may have catcalled from a car — front seat, passenger side — on the 600 block Bush Street in San Francisco one summer night in 1979.

One of my first lessons was in objectification: seeing women as objects. This is not news to you, and you have probably heard this terminology before: objectifying. That seemed like an easy lesson to comprehend: women are not like furniture or cars or appliances; they are not like objects. But then I began to think about it as a form of grammar: subjects and objects. Subjects cause things and do things, like in the subject of a sentence: Billy threw the frog at the girl. Billy is the subject; the girl is the object. Billy does the action; the girl is on the receiving end of it. That’s how grammar works in sentences: subjects and objects. To objectify is to dehumanize: to catcall from a car, and, arguably, to view pornography, is to dehumanize the objects of those actions, and in both cases, the woman is the object.

[P] Dehumanizing — to take away someone’s subject agency, to reduce them to an object — is an ethical issue. I wonder sometimes about people’s use of the word “girl” in academic and professional environments. [I] According to the Oxford English Dictionary, one meaning of the word “girl” is an “often derogatory reference to women with respect to their occupation or social status.” [E] As much as I like to use that example in my writing classes (the rhetorical and ethical implications of girl vs. woman) I don’t think it does the work I want it to do: to show the dehumanizing effect.

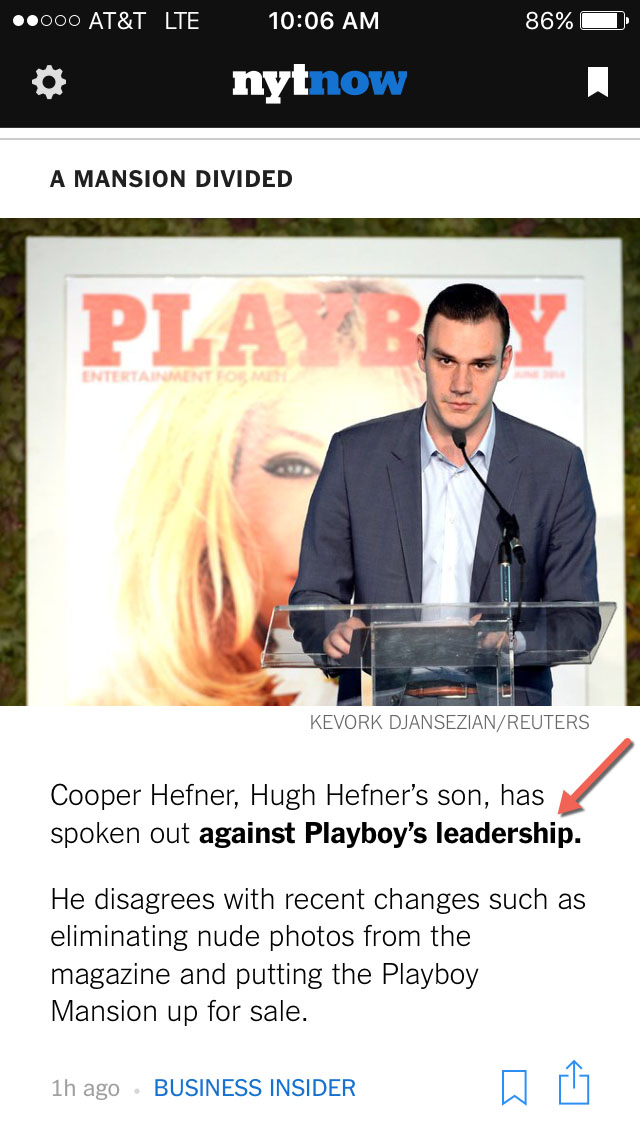

But since I read the New York Times in my classes, I do not have to look far for other examples. Two recent instances serve my purposes here, both having to do with Playboy magazine. On February 4th: “Playboy Puts On (Some) Clothes for Newly Redesigned Issue,” written by a man, takes a fairly flippant tone and view in wondering “What is Playboy without naked women?” Because the article appeared in the New York Times, which I appreciate for its careful analysis and cultural critique, I assumed there would be some discussion, some hint that there might be a problem associating women’s bodies with commodities like oil, wheat, and currency — objects that are traded on the open market for profit — but no:

It is now pitched squarely to millennials and the era of the smartphone. The cover displays a winsome young woman whose arm extends straight out of the frame, as if she were taking a selfie. In a familiar font, it reads, “heyyy ;)” beneath her. It’s like a virtual come-hither, via Snapchat.

How exciting for millennials that the “slightly saucier version” of Playboy and its new “strategic concealment” of somewhat-naked women is being targeted directly toward them, what with their current lack of sources for naked and nearly naked women.

Example #2: not only is it okay to trade in women’s bodies for profit, it is now even a sign of leadership:

I have a million intellectual, cultural, and academic examples like that on my bookshelves, in my browser bookmarks, in the collected essays written by young women on what it feels like to be catcalled — humiliating, shamed, dehumanizing, embarrassing, self-conscious, subjugated, a complete and total loss of dignity, powerless — in wage-gap research, the effects of performative gender roles, and in the history of fashion photography. Most days they feel like distant examples. Academic. It’s when I recall my good fortune to teach at a university where two-thirds of the students are women that I always feel the opportunity to use the second half of my life to make up for and to apologize for the first half of my life. In fact, I also perceive many opportunities to work with and to educate young men on these issues.

But this is where the real problem — an unavoidable reality — announces itself: I can do this work only because I am a man. If my female colleagues took strong advocacy positions like mine – -queried you in class about your attitudes toward feminism, for example — they would be criticized as being too political or too stridently feminist or trying to indoctrinate you via a feminist perspective. I can do what I do because of my unearned male privilege.