Let’s begin with a claim: teaching and learning without reflecting on how, what, and why we are teaching and learning is meaningless. In First Year Writing, we believe that a digital writing portfolio is the best platform — like a dot-connecting mechanism — for reflecting on the work you’ve done and will be doing in the future.

Project: First Year Writing Digital Portfolio

Audience: Instructor, classmates, WRD/FYW administrators, university assessment committees

Attitude: The very best digital writing portfolios are framed with an exploratory essay and approach; you may not know the answers to the questions that are being posed to you here, and that’s okay. Use this essay to figure them out, to make sense of your writing, and to make sense of yourself as a writer.

A note on reflection

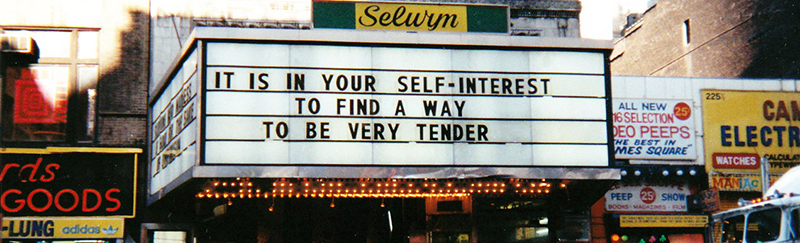

Reflection refers to the iterative process that we engage in when we want to look back at some activity or decision we’ve made, to think about what we’ve learned from it, and how we might use it in the future. Reflection is a powerful tool in teaching and learning, and outside of academics, reflecting is a common tool among professionals and organizations as a way to establish values, goals, and future actions:

- What did I do? What is significant about it?

- Did I meet my goals?

- When have I done this kind of work before? Where could I use this again?

- Do I see any patterns or relationships in what I did?

- How well did I do? What worked? What do I need to improve?

- What should I do next? What’s my plan?

WRD104 Digital Writing Portfolio Requirements

Part I: Contextual Analysis Process Description: a paragraph-by-paragraph map and reflective postmortem.

[process-description.doc]

Part II: Writing about writing — compose a 1000-1250 word exploratory essay based on the Habits of Mind Framework. Which of those habits are part of your daily practice — provide specific examples from our course and link to them — and which habits are not part of your daily practice? Assess your own work in this class, showing where, for example, curiosity led you down a good, productive, generative road — where you challenged yourself, really stretched yourself, intellectually — or how you perceive your lack of curiosity affecting your work. Show us where your lack of openness might have closed of routes of inquiry.

Describe moments of engagement where you contributed to the intellectual life of our course — or not, and why not — or where your persistence paid off on a particular project, of if not, why not. In terms of responsibility, what resources did you identify in your quiver, and how did you use them?

Because this is a writing portfolio, readers will expect to see some discussion of your process: provide examples from a before-and-after PIE paragraph, before-and-after paragraph transitions, before-and-after integration of quotes.

Additional possible prompts:

Your Print/Digital Reading Process Project was an opportunity to reflect on yourself as a reader, and what kind of reader you are: aesthetic, efferent, forager. What did you learn about yourself as a reader? How fair were you to Schenwar’s Too Many People in Jail? Abolish Bail. Do you think that reading can be an act of composing? Do you think that you make meaning in the act of reading?

Your Print/Digital Reading Process Project was an opportunity to reflect on yourself as a reader, and what kind of reader you are: aesthetic, efferent, forager. What did you learn about yourself as a reader? How fair were you to Schenwar’s Too Many People in Jail? Abolish Bail. Do you think that reading can be an act of composing? Do you think that you make meaning in the act of reading?- What does it mean to have empathy for readers and for writers? Do you have it? Empathy for readers and for writers?

- Where did you feel yourself tempted to bullshit? What did you do?

- If you could start your Contextual Analysis Project all over again, what would you do differently? Why?

- Arthur Miller — “A good newspaper, I suppose, is a nation talking to itself.” Thoughts?

- Is “good writing” a result of ongoing rigorous critical and reflective thinking? How do you know? Don’t take my word for it — really: how do you know?

- What’s in your self-editing toolkit? Reflect on your brainstorming, discussing, drafting, researching, revising, editing, proofreading strengths & challenges.

- How comfortable are you with ambiguity? Some people are fine with open-ended exploratory projects — “I’ll figure it out as I go” — and others need and want specificity, concreteness, a sense that there must be right or wrong answers. Which are you, and how do you suppose that affects your critical thinking and writing? Provide specific examples from your work — quote from them and link to them.

- I like addressing you as “educated, intellectually engaged, curious, culturally and civically aware citizens, critical thinkers, and NYT readers” — but what if you don’t aspire to those values and find them off-putting? What’s it like to be in a class like that twice a week for 10 weeks, and how do you suppose that affects your critical thinking and writing? Provide specific examples from your work — quote from them and link to them.

- Habits of Mind: curiosity, openness, engagement, creativity, persistence, responsibility, flexibility, metacognitive awareness: your teacher loves those things and sees value in them. Do you? Do you see value in them? Can you weigh yourself against them? Provide specific examples from your work — quote from them and link to them. (This would also make an excellent first sentence in your reflective essay: “I’ve been thinking about these ‘Habits of Mind’ and am not sure where I fit with all of them.” Any reader would be eager to read the next sentence!)

- [5/27 post-class brainstorming follow-up]: I was really struck by Joe L.’s combining yesterday of “argumentative” and “mean.” Pretty interesting! I’m familiar with “saloon arguments,” where (mostly) old people sit in bars yelling at the TV and each other. Those are saloon arguments.

But what we do, if I read our syllabus correctly, is to “prepare you to take those productive ideas into other courses and out into the world, where they belong, and where you can defend them and advocate for them.” http://composing.org/wrd104sq2015/welcome-to-wrd104/ In other words, we test ideas with each other in our class — finding out which ones might float, and why, and which ones won’t, and why.

It’s a beautiful thing. I find that kind of work pretty powerful.

Ideas presented persuasively are usually successful because they depend on some sense of shared values; they acknowledge listeners’ and readers’ values, experiences, assumptions, biases, expectations, and ideologies; they respect listeners’ and intelligence.

Those that are not persuasive don’t do any of those things.

And to make matters worse — or better, depending on your perspective: I don’t think of you as first- or second year students. Rather, I think of you as future leaders in the Vincentian tradition.

And because Sofia mentioned learning about theories in other classes, and then being tested on them, we were also able to have a related conversation about the social aspect of learning and teaching: we can only make sense of our course materials and challenging ideas with each other. In fact, it’s in our FYW Learning Outcomes: “Explain the collaborative and social aspects of writing processes.”

That would be some top-shelf, sophisticated reflection, if you were willing to work through those issues in your reflection — what does it feel like to test ideas? What went well? What didn’t? What might you do differently next time?

- 6/3 post class brainstorming followup, including our Editing checklist

Happy reflecting!